Advertising on search engines is a major expense for many companies. In 2015, their total estimated spend was $170 billion. But it is difficult to correctly measuring the returns to search engine marketing.

Some observational studies simply count the traffic or revenue generated from paid search traffic (Ramos and Cota 2008) or similar methods (Chan et al. 2011). This overlooks an important selection problem, however. Many individuals who see a paid link for a site when they search may have intended to visit that site anyway; even though they click the sponsored link, the link's presence did not cause the searcher to visit the site. Simply counting clicks ignores this, and potentially overstates the benefits of search engine marketing.

The effectiveness of branded search ads: The example of eBay

Blake et al. (2015) performed a pioneering study designed to avoid this problem, based on a randomised control trial that experimentally manipulated the availability of paid search advertising for branded search involving eBay. These are searches that include the ‘brand’ (in this case, eBay) plus some other terms, such as “eBay motorcycle”, or “used guitar on eBay”. Brand search ads are displayed as a result of this brand search. They appear at the top of the first page of results.

According to this study, if eBay were to shut off its branded search advertisements, the volume of traffic to the eBay website would remain virtually unchanged. Traffic would still flow through the organic (unpaid) search results, which cost eBay nothing. The authors conclude that:

“[F]or brand keywords, natural search is close to a perfect substitute for paid search, making brand keyword SEM [search engine marketing] ineffective for short-term sales. After all, the users who type the brand keyword in the search query intend to reach the company’s website, and most likely will execute on their intent regardless of the appearance of a paid search ad.”

Branded search ads may be the most substitutable category in paid search advertising, because when we type the name of a company in the search bar, we probably intend to visit that company's web site. Blake et al. drew their conclusion from the extreme case of eBay, which is one of the largest companies in the world. This is nevertheless a challenge to the industry – is brand search a waste of money for companies?

A smaller brand

In a recent paper, we use a similar approach but with a company much smaller than eBay (Coviello et al. 2017).

We run our field test on Edmunds.com (http://www.edmunds.com), an online resource for automotive information in the US. Edmunds.com is not an extreme case like eBay, but it has an Alexa rank (which measures popularity over the previous three months based on a combination of page views and unique visitors) of 559 within the US. This places it well within the top 1% of most-visited websites.

With 700 employees and over $200 million in annual revenue, Edmunds.com is a large US company with a strong online presence. It faces a more competitive marketplace than eBay, however, with competitors of similar size, popularity, and services.

The unit of observation in our study is geographic markets in the US, the so-called designated market areas (DMAs). Edmunds.com uses branded search advertising in all 210 DMAs. For our study, we randomise half the markets, balanced by market size and penetration of Edmunds.com, into control and treatment groups. We monitor web traffic from August to November 2015 for each of these markets, distinguishing organic from paid traffic.

After a baseline measurement period, branded search advertising is shut off for the 105 markets in the treatment group. This approach allows us to obtain a precise (difference-in-differences) estimate of the effect of branded search advertising on overall web traffic and its components.

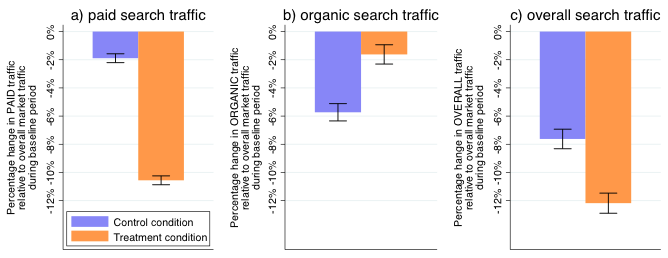

Our design allows us to study how organic traffic responds to a sharp decrease in search-engine advertising, and to find out the extent to which users find their way to Edmunds.com regardless of the presence of paid search ads, given that they started out with a search involving the company’s name. The results from the experiment are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The response of organic traffic to a decrease in search engine advertising

Source: Own calculations based on data from Coviello et al. (2017).

Figure 1 plots three measures of the relative change in web traffic for each of the DMAs: paid traffic, organic traffic, and their sum, total web traffic. All changes are normalised to average overall traffic of a market during the baseline period of the experiment, to avoid issues of scale with DMAs of different size.

Panel (a) shows the change in paid search traffic in the control and treatment markets. While control markets experienced a small drop in paid traffic in the intervention period, paid traffic plummeted to nearly zero in the treatment markets. This is no surprise, since we shut off this channel. The difference between the two bars is the loss in paid web traffic due to the experiment. Thus, our experiment induces a large and highly significant difference in paid traffic between control and treatment markets.

Panel (b) shows how organic web traffic changed between the baseline and experimental period. While the decline in the control group shows the overall trend in organic searches was down, the treatment group surged relative to that trend. Thus, shutting off paid traffic increases organic traffic. This difference is, again, highly significant.

However, the increase in paid traffic isn’t nearly as large as the loss in paid traffic. As panel (c) shows, treatment markets lost much more overall traffic than control markets, a highly significant difference. The overall loss isn’t as large as the loss in paid traffic, as the increase in organic traffic partially compensates for it. Still, more than half of the paid traffic is lost.

Paid brand search increases traffic

Our results contrast with those obtained by Blake et al. (2015) for eBay. Only about half of the traffic normally flowing to Edmunds.com through branded search ads still flowed to the website when it relied only on organic search links. It is likely that the other half landed on the pages of the competitors who used paid search and had bid on the keyword “Edmunds”.

The effect is particularly large in local markets with a high share of traffic from branded search ads in the baseline period. In these markets, Edmunds.com lost about 72% of this traffic as result of shutting off its paid brand search. That is, only 28% of branded search traffic still accesses the website via organic search links.

Blake et al. (2015) found 99.5% substitution for branded search ads traffic for eBay. We found that substitution was less than 50% for Edmunds.com. Our results suggest that for a company in the top 1% of the most-visited websites, paid brand search advertising increases traffic to the website, both statistically and economically.

We do not yet know why there is such a difference in results between eBay and our experiment. Given the amount of money poured into online marketing, this is a worthy question for future research.

References

Blake, T, C Nosko, and S Tadelis (2015), “Consumer Heterogeneity and Paid Search Effectiveness: A Large-Scale Field Experiment”, Econometrica 83(1): 155– 174.

Chan, D X, Y Yuan, J Koheler and D Kumar (2011), “Incremental Clicks: The Impact of Search Advertising”, Journal of Advertising Research 51(4): 643.

Coviello, L, U Gneezy and L Goette (2017), "A Large-Scale Field Experiment to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Paid Search Advertising", CEPR Discussion Paper 12333.

Ramos, A and S Cota (2008), Search engine marketing, McGraw-Hill Inc.