In 1919, the UK established an agency to promote its exports and reduce unemployment by acting as the “guarantor of the last resort”. One hundred years later, the phenomenon has spread across all OECD countries and many others, with the value of new government-backed guarantees totalling approximately US$1 trillion in 2017 (Berne Union 2018).

Such guarantees could reduce the information frictions that plague contemporary cross-border trade (Allen 2014). Governments may offer guarantees to decrease the commercial and political risks of non-payment and improve liquidity. In this way, governments may facilitate trade and trade credit financing (Funatsu 1986, Heiland and Yalcin 2015). Reducing trade costs enables more companies to export and also increases export of the most productive companies (Melitz 2003).

But what does experience tell us about the effects of these guarantees? So far, research on guarantees is mostly limited to studies on macro-level data that find a positive association between guarantees and aggregate exports. Since aggregated studies may be contaminated by bias from omitted variables and sample selection, there are now a few firm-level studies. Using Austrian and German data, these studies indicate that guarantees are positively linked to firm exports (Badinger and Url 2013, Heiland and Yalcin 2015), sales, and employment (Felbermayr et al. 2012). The link to exports appears stronger for smaller firms (Heiland and Yalcin 2015).

Swedish evidence from transaction-level data

In a recent paper (Agarwal et al. 2019), we add to this research by providing the first quasi-experimental evidence on the effects of guarantees on firm-destination trade margins, as well as the first population-based evidence on the firm-level effects on jobs, value added, and productivity. We also examine how insurance facilitates foreign trade, distinguishing between a reduction in the default risk and in the liquidity constraint. Our research is based on Swedish longitudinal transaction-level data on insurance, as well as granular data on exporters and foreign buyers.

In Sweden, the Export Credit Agency annually provides new guarantees worth approximately $5 billion (SEK 40 billion). In 2017, the agency had some 400 customers and covered between 1,500 and 2,000 business transactions to over 130 foreign countries. The value of all guarantees outstanding was $21,256 million (SEK 181,485 million).

Compared with other firms, the firms that choose to use guarantees typically have higher turnover and a higher proportion of skilled personnel, participate to a greater extent in foreign trade, but are foreign-owned to a lesser extent. The destination countries are often more distant, have higher market risk, and more often lack free trade agreements with the EU.

Though SMEs account for more than 99% of all export firms, nearly a third of total exports and for the majority of foreign buyers, we find that they are underrepresented in guarantees. Looking at exporters in 2018, SMEs accounted for a third of the number of new guarantees and only 4% of the value of new guarantees. In other words, there is a discrepancy whereby these companies account for an important part of exports but a disproportionately small part of the value.

The effects of guarantees on firm performance

Our first approach is to compare the difference in firm performance between firms that use a guarantee to a destination in a certain year but not the year before, and firms that did so in neither year. Specifically, we apply a difference-in-differences (DD) matching estimator, to control for selection into treatment and to create a comparison of the de facto outcome and its counterfactual. The analysis results in three main findings.

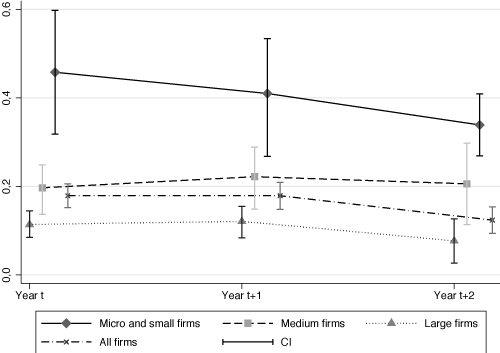

First, a guarantee increases the firm’s contemporaneous probability of exporting to a foreign market by 18 percentage points and the effect lingers the year after, compared with control firm destinations (see the top panel of Figure 1). What’s more, the effect for micro and small companies is two and four times larger than that for medium-sized and large companies, respectively.

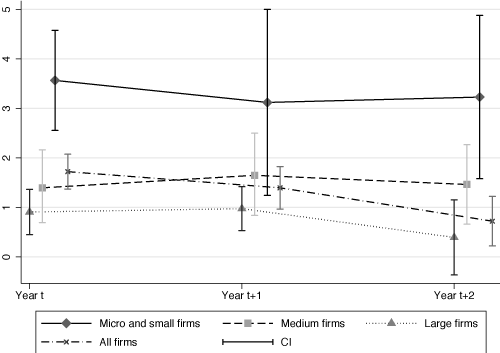

Figure 1 Change in probability of exporting (top panel) and in export value (bottom panel)

Note: The figure reports changes in the probability of exporting (top panel) and in export value (bottom panel). The vertical axis measures the change from year t-1 for the treated firm-country dyads relative to the one for their matched controls. The results (coefficients and 95% confidence intervals) are from matching and difference-in-difference estimations with firm-/industry-year and country-year fixed effects.

Source: Results from Agarwal et al. (2018).

Second, guarantees affect the export value of small companies more positively (see the bottom panel of Figure 1). While the overall export value increases 213 percentage points more than for control companies, for smaller companies it is more than twice as large. (Omitting zero trade, the pattern is the same across firm-sizes while the magnitude is about 12 percent of the original one, hence, overall, we then find a 26 percentage point increase in export value.) We also note that the export effect is noticeable several years after the guarantee is issued, which could indicate a spillover effect to other customers in the market.

Third, we find that guarantees do not generally have an economically or statistically significant impact on jobs and productivity. This is interesting as export credit authorities were originally established with these variables in mind and job creation still is mentioned as a target. Assuming that such effects can occur, a possible explanation for why we do not find them is that guarantees increase exports, but that companies do not need to adjust their production significantly. After all, sales in exports take place at the margin, being dominated by domestic sales. However, for first-time users of guarantees for a specific market and for smaller transactions, we do find an impact on value added, jobs, and productivity.

Novel quasi-experimental evidence

We also approach the phenomenon by exploiting a quasi-natural experiment. Between 2012 and 2016 the Swedish agency ran several direct marketing campaigns to increase knowledge of guarantees and attract customers among exporting SMEs. They approached approximately 15,000 firms annually – 5% of all SMEs, but 70% of those that export. The key criterion for being included in the campaign was having fewer than 250 employees, besides being an exporter.

This setting is suitable for employing a fuzzy regression discontinuity (FRD) design, using the employment criterion to control for unobserved factors that may affect selection into using guarantees. We argue that the employee criterion makes the probability of treatment random, around the threshold value, since the controls were as likely to get the information had they only had slightly fewer employees. In this way we capture the local treatment effects around the discontinuity of 250.

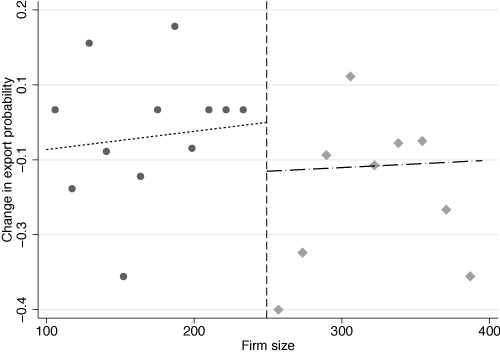

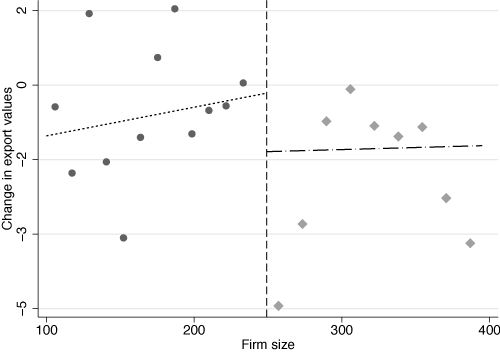

Figure 2 Fuzzy regression discontinuity design

Source: Agarwal et al. (2018).

The FRD in Figure 2 reveals that the probability of exporting increases by 12 percentage points and that the value of exports also increases substantially. We interpret the results as evidence corroborating a causal effect of guarantees on firm performance.

Concluding remarks and policy implications

Our results provide evidence that guarantees have a causal but heterogeneous effect on firm performance. Guarantees most strongly facilitate the entry of less well-endowed and internationalised firms into foreign destinations and substantially sustain existing exports there. We also find effects on jobs, value added, and productivity for new users of insurance and for small transactions.

Seeing that small and less-experienced firms benefit the most, we consider whether governments should rebalance the provision of guarantees in favour of such firms. It is well documented that SMEs experience less favourable conditions for the financing of growth and exports (Camp 2019, WTO 2016, World Bank 2018). At the same time, smaller and younger companies are important for job creation and future exports.

Considering larger companies, for which the export effects are relatively minor, the question is to what extent and under what conditions they need guarantees. On the one hand, these companies generally have good opportunities to export on their own or by involving private insurers, but on the other, they also face harder competition from dynamic markets and frequently on unequal terms, as is discussed below. And when it comes to really large transactions, the chances are not even big companies can bear the risks themselves or acquire private insurance. Similarly, both large and small companies may need guarantees during macroeconomic shocks such as the recent financial crisis.

Our final concern is competition from exporters in countries that have not joined the OECD's Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits. This arrangement was put in place to prevent guarantees being used as a disguised trade policy tool to increase a country's own exports at the expense of others. But as world trade patterns have changed, countries not part of the agreement, such as India and China, have come to account for a large and rapidly growing part of trade and guarantee issuance. China has increased its issuance of guarantees from almost $43 billion to $327 billion between 2008 and 2013 (OECD 2015). It is now the world’s largest provider and has an unprecedented export penetration ratio.

Rather than having the parties of the OECD arrangement beginning to subsidise their guarantees vis-à-vis such competition, governments should urgently step up work to ensure a transparent and regulated system for guarantees that incorporates all major countries. Properly designed, guarantees could increase foreign trade, thereby contributing to welfare.

References

Agarwal, N, M Lodefalk, A Tang, S Tano, and Z Wang (2018), “Institutions for Non-Simultaneous Exchange: Microeconomic Evidence from Export Insurance”, Working Paper 12/2018, Örebro University School of Business.

Allen, T (2014), “Information frictions in trade”, Econometrica, 82 (6), 2041–2083.

Badinger, H, and T Url (2013), “Export credit guarantees and export performance: Evidence from Austrian firm-level data”, World Economy, 36 (9), 1115–1130.

Berne Union (2018), Berne Union Yearbook 2017, TXF Publishing: London.

Camp, P (2019), 2019 Global Survey – Overcoming the Trade Finance Gap: Root Causes and Remedies, BNY Mellon, New York.

Felbermayr, G, I Heiland, and E Yalcin (2012), “Mitigating liquidity constraints: Public export credit guarantees in Germany”, CESifo Working Paper Series 3908.

Funatsu, H (1986), “Export credit insurance”, Journal of Risk and Insurance, 53 (4), 679-692.

Heiland, I, and E Yalcin (2015), “Export market risk and the role of state credit guarantees”, CESIfo Working Paper No. 5176.

Melitz, M (2003), “The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity”, Econometrica, 71 (6), 1695-1725.

OECD (2015), “Chinese Export Credit Policies and Programmes”, Report TAD/ECG(20015)3.

World Bank (2018), Improving Access to Finance for SMEs – Opportunities through Credit Reporting, Secured Lending and Insolvency Practices, World Bank Group: Washington.

WTO (2016), Trade Finance and SMEs – Bridging the Gaps in Provision, World Trade Organization, Geneva.