Budgetary forecasts are more than a valiant attempt to divine future outcomes. They shape them. To ensure accountability, in democratic societies fiscal policy is based on detailed draft budgets to be adopted by parliament. Expenditure programmes are presented alongside revenue projections, which in turn are tightly linked to macroeconomic forecasts. If lawmakers have a sanguine view of the future they will expect higher revenues and plan higher spending; if they are prudent, they will formulate more cautious projections coupled with equally prudent expenditure plans.

Sound macroeconomic and budgetary projections are not only relevant in a national context. They also play a crucial role for the smooth functioning of the Economic and Monetary Union of the EU. In a system that combines centralised monetary policy with decentralised budgetary policies, national fiscal developments can spill over to other countries and need to be coordinated. That is why the EU’s economic governance framework encompasses the obligation for each member state to submit every year its short to medium-term budgetary plans to Brussels for joint scrutiny. These plans are called stability programmes for euro area countries and convergence programmes for those who have not (yet) adopted the single currency. The underlying idea is to detect and possibly correct in advance developments that are in conflict with the commonly agreed fiscal rules, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). In the past, the Stability and Convergence Programmes (SCPs) had to be submitted to the European level in the autumn of each year. Since 2011, they are submitted between mid and end April. This change was meant to strengthen multilateral fiscal surveillance by giving the Commission and the Council potentially more time to raise possible issues before the budget plans are adopted by national parliaments.

The assessment of the SCPs naturally starts with a careful analysis of the macroeconomic projections underpinning fiscal plans. While such ex-ante assessments are an essential element of peer pressure, forecasts are inherently uncertain and will always miss the mark. To discriminate bad luck from a possible bias, ex-ante assessments need to be complemented by a more analytical examination covering several years. Early examples of such examinations are Strauch et al. (2004), Jonung and Larch (2006) and Beetsma et al. (2009), all pointing to some systematic gaps between good intentions and delivery.

In a recent paper (Beetsma et al. 2022), we take a fresh look at the issue with a significantly larger dataset covering both more years (1998–2020) and countries (all 27 EU countries). Apart from assessing the statistical quality of the official budgetary projections, we also analyse the drivers of the budget balance errors and the potential role played by national independent fiscal institutions.

Main results

It is well understood that any macroeconomic and budgetary forecasts are likely to be revised over time. However, in the absence of an unexpected large shock, these corrections should ideally be moderate in scale and more importantly unbiased. In reality, studies have shown that forecasts errors are persistently sizable and that governments tend to be overoptimistic in their budgetary plans (Merola and Perez 2013, Debrun and Kinda 2017, Flores et al. 2021, Gootjes and De Haan 2021, Larch et al. 2021).1

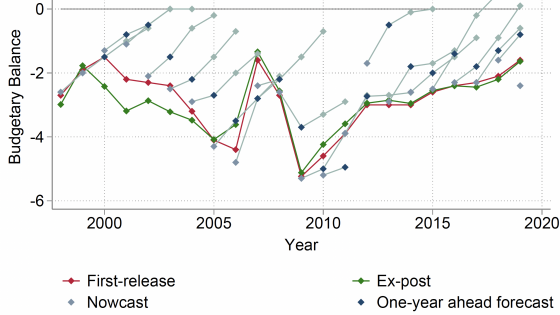

In the EU this can be illustratively exemplified by the case of Italy. Figure 1 shows the forecasted/estimated budgetary balance for given years at different points in time (vintages). The dark blue diamonds depict the budget plans made one year before the year for which the budget is drafted. The red diamonds are the ‘first-release’ estimates, which are made one year after the year in question. This measure of the budgetary balance is of particular relevance in the European context since it forms the basis for the real-time monitoring by the fiscal authorities and financial markets. The vertical difference between the red diamond and the dark blue diamond is the first-release forecast error in the budget balance. The patterns from this are clear: (1) revisions are large and persistent, (2) the envisaged budgetary position becomes more ambitious for years further into the future, (3) budgetary plans systematically fall short of original projections, and (4) ex post (final) data show that budgetary estimates are still revised over time, largely due to methodological shifts.

Figure 1 Budget balance projections, first-release and ex-post for Italy

Source: Stability and Convergence Programmes.

Note: Nowcasts are the figures reported in the reference year, first-release figures are reported in the year after the reference year, one-year (two-year, three-year) ahead forecasts are constructed in the year (two years, three years) preceding the reference year and the ex-post figures are the figures reported for the reference year in the most recent data vintage used.

This pattern also holds for other member states such as Belgium or Portugal. However, contrary to previous studies, our results show that, on average across all EU sample countries, the budgetary forecast error is close to zero. This is due to stark differences across countries: some exhibit a systematic overoptimism while others follow a path of overpessimism. This is not to say that forecast errors are irrelevant from the EU perspective because they wash out in the aggregate. Quite the opposite: in a currency union where national fiscal policymaking remains firmly in the hands of individual members states, systematic or major policy mistakes can and do spill over to other countries and may affect the stability of the union as a whole.

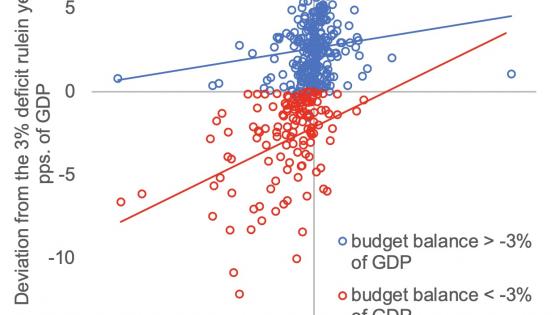

From a policymaking perspective, the key question then is: what drives these forecast errors? The exploration of the data demonstrates that the most important explanatory variable of the first-release budget error is the first-release (real) GDP growth error (see Figure 2). This seems intuitive since budgetary projections rely on projections of economic growth. A negative or positive growth surprise will thus have serious budgetary implications. The econometric analysis suggests that a first-release error in real GDP of one percentage point due to overoptimism leads on average to a worsening of the budget balance of ¼ percentage point.

Figure 2 Relationship between growth and budgetary forecast error

Source: Stability and Convergence Programmes.

Note: The graph excludes three data points, namely, Greece in 2009, Ireland in 2010 and Slovenia in 2013. In these instances, the countries recorded a first-release error in the budget balance of respectively -9.8%, -20.8% and -12.2%.

To understand this relationship better, a more granular analysis focuses on a decomposition of first-release budget balance errors into first-release revenues and spending errors. These errors are further split into base, growth and denominator effects (see Table 1).2 Overly optimistic real GDP growth forecasts lead to higher revenue and spending shares of GDP than projected. This is partially explained by the fact that revenues and expenditures are expressed as a percent of GDP. However, the decomposition shows that this relationship goes beyond a mere ‘mechanical’ denominator effect. Revenues tend to follow overall GDP dynamics, while expenditures are not directly adjusted to an unexpected shortfall in output, which illustrates the operation of automatic stabilisers. A negative one percentage point surprise in nominal GDP growth produces a -0.7 and +0.4 percentage point shift in budget balance via the growth effect channel of revenues and spending, respectively.

Table 1 Averages of the forecast errors and their components

Note: The denominator effect needs to be subtracted from the sum of the other two effects to arrive at the overall error. A difference may result because of rounding errors.

The analysis also shows how governments adjust to a forecast error in the preceding year – a sort of learning/compensation effect. If expenditures overshoot the projection in the previous year, governments tend to aim to revise spending downwards for the next period. This is a welcome reaction from a budgetary planning/sustainability perspective. On the other hand, an overshoot of revenues in the previous period leads to an increase in expenditures in the following period – suggesting that governments spend windfall revenues rather than building up fiscal buffers.

Conclusions

The importance of the first-release GDP growth forecast error for accurate budgetary projection provides some food for thought for the architecture of the EU and national fiscal frameworks. An institutional setting that generates more accurate and less biased macroeconomic forecasts will greatly improve budgetary planning. The SGP’s ‘six-pack’ reform of 2011 requires that national GDP growth projections be either constructed by an independent institution or at least be endorsed by them. A decision of non-endorsement presents a ‘nuclear option’, which the independent institution will only use as a last resort, thereby giving governments some wiggle room in their forecasts. It is therefore preferable that the national independent fiscal institutions are directly tasked with producing macroeconomic forecasts, since it facilitates truly independent projections. In practice, this setting is the less prevalent one in the EU. Irrespective of this choice, the analysis hints that the presence of independent fiscal institutions tasked with endorsing or producing GDP forecasts bolsters the accuracy of budgetary plans if the institution enjoys a high media presence, which strengthens its role in the public discourse and gives more weight to their assessments.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect the official position of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated or for which they work.

References

Beetsma, R, M Giuliodori and P Wierts (2009), “Planning to Cheat: EU Fiscal Policy in Real Time”, Economic Policy 24(60): 753-804.

Beetsma, R, M Busse, L Germinetti, M Giuliodori and M Larch (2022), “Is the Road to Hell Paved with Good Intentions? An Empirical Analysis of Budgetary Follow-up in the EU”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17154.

Debrun, X and T Kinda (2017), “Strengthening Post-crisis Fiscal Credibility – Fiscal Councils on the Rise. A new dataset”, Fiscal Studies 38(4): 667-700.

Flores, J E, D Furceri, S Kothari and J D Ostry (2021), “The reliability of public debt forecasts”, VoxEU.org, 28 May.

Gootjes, B and J de Haan (2021), “Procyclicality of Fiscal Policy in European Union Countries”, Journal of International Money and Finance, forthcoming.

Jonung, L and M Larch (2006), “Improving Fiscal Policy in the EU: the Case for independent Forecasts”, Economic Policy 21: 491–534.

Larch, M, J Malzubris and M Busse (2021), “Optimism is bad for fiscal outcomes", VoxEU.org, 04 November.

Merola, R and J Pérez (2013), “Should the role of preparing budgetary projections be delegated to an independent agency?”, VoxEU.org, 01 May.

Strauch, R, M Hallerberg and J von Hagen (2004), “Budgetary Forecasts in Europe – the Track Record of Stability and Convergence Programmes”, ECB Working Paper No.30.

Endnotes

1 Before the introduction of the European Semester the projection for year t is released in the fall of year t-1, while after its introduction, the projection for year t is released in the spring of year t-1, based on the moment of release of the SCPs.

2 The ‘base effect’ captures the update of the value of a variable pertaining to a given year as time passes due to new available information or a change in methodology – i.e. largely mechanical effects. The ‘growth effect’ is the difference between the first-release nominal growth in revenues or spending (in euros) and the projected nominal growth in revenues or spending (in euros), with some weighting factor. The ‘denominator effect’ is the first-release error in nominal GDP growth with the same weighting factor.