“We very, very much did not want to make the loan.”

Ben Bernanke testimony (10 October 2014) regarding the Federal Reserve’s emergency provision of credit to AIG in September, 2008.

More than six years after the Dodd-Frank Act passed in July 2010, the controversy over how to end ‘too big to fail’ (TBTF) remains a key focus of financial reform. Indeed, TBTF – which led to the troubling bailouts of financial behemoths in the crisis of 2007-2009 – is still one of the biggest challenges in reducing the probability and severity of financial crises. By focusing on the largest, most complex, most interconnected financial intermediaries, Dodd-Frank gave US officials a range of crisis prevention and management tools. These include the power to designate specific institutions as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs), a broadening of Fed supervision, the authority to impose stress tests and living wills, and (with the FDIC’s Orderly Liquidation Authority) the ability to facilitate the resolution of a troubled SIFI. But, while Dodd-Frank has likely made the US financial system safer than it was, it does not go far enough in reducing the risk of financial crises or in ensuring credibility of the resolution mechanism. It is also exceedingly complex.1

Against this background, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2016) recently announced The Minneapolis Plan to End Too Big to Fail (‘the Plan’). While the Plan raises issues that require further consideration – including the potential for regulatory arbitrage and the calibration of the tools on which it relies – it is straightforward, based on sound principles, and focuses on cost-effective tools. In this sense, the Plan represents a big step forward.

The problem of too big to fail

The TBTF problem is simple. It comes down to this – facing the looming failure of a SIFI, a government can be expected to bail out the private institution’s creditors rather than allow the country to suffer an economic and financial collapse. The historical record is littered with examples of such bailouts. The 2007-09 experience, when US regulators did this repeatedly, is just the most recent example; and one that we should never forget.

Simply declaring TBTF illegal and forbidding government bailouts may be popular, but it lacks credibility. TBTF is a classic problem of time consistency – a future government facing a crisis will renege on the promise not to bail out private creditors. If necessary, it will change the law, as the US Congress did when it approved the $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program in September 2008. As a result, today’s SIFIs and their creditors have a clear incentive to take risks that raise the chances of a financial crisis.

What to do? The answer is that we need a regulatory framework that severely reduces the probability of a crisis as well as the potential contagion from the resolution of troubled intermediaries. This may mean trading off economic efficiency for financial safety. But, as we have discussed in Cecchetti and Schoenholtz (2014b), the social costs seem likely to be lower than many argue.

A key virtue of the Minneapolis Plan is its realistic assumptions. The first is that SIFIs (designated or not) will be bailed out in a crisis; the second, that making the financial system safe will involve some up-front costs; the third, that a future government will be unwilling to impose losses on SIFI creditors during a period of widespread financial distress. Implicitly, the Plan further assumes that regulators are not capable of anticipating all the key vulnerabilities of the financial system, so that preventing future crises requires making the financial system resilient to all types of large shocks.

Key features

The Minneapolis Plan has four key features:

- A sharp increase in requirements for loss-absorbing equity capital (not debt) at the 13 largest, most complex, and most interconnected US banks (currently those with at least $250 billion in assets), to be phased in over five years.

- A further sharp hike in capital requirements after five years for each bank unless the Treasury Secretary certifies that it is no longer systemically important.

- A tax on borrowings by shadow banks – based on the types of shadow banks defined by the Financial Stability Board (2015) – calibrated to match the increased funding costs of the ‘covered’ group (with a higher tax rate on shadow banks that the Treasury Secretary considers systemic).

- A relaxation of regulation on banks with up to $10 billion in assets. (As described in FDIC (2016), these make up 98% of insured US banks, but account for less than 19% of the insured deposit base.)

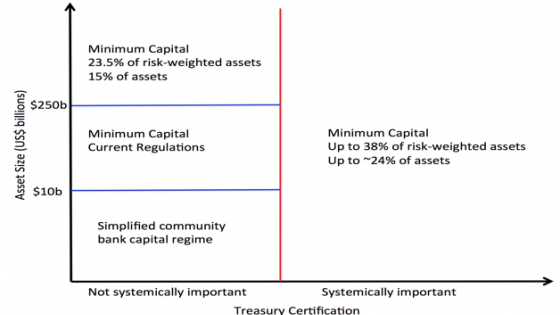

Figure 1 illuminates the Plan’s impact on the US banking sector. Following a five-year transition, covered banks will need to finance 23.5% of their risk-weighted assets (RWAs) with equity (formally Common Equity Tier 1).

Based on end-2015 covered bank reporting, the Plan translates the 23.5% RWA requirement into a pure leverage requirement (the ratio of common equity to total assets) for covered banks of 15%. For comparison, the FDIC’s mid-2016 Global Capital Index (FDIC 2016b) reports that the average Tier 1 capital ratio of the eight US global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) equals 13.55% of RWA and, under GAAP accounting, 8.24% of total assets. Moreover, after five years, unless the Treasury Secretary certifies that a covered bank is no longer systemic, its required capital ratio would rise by five percentage points per year to a peak of 38% of risk-weighted assets (equivalent to an unweighted leverage ratio of nearly 24%). Finally, banks with assets fewer than $250 billion and more than $10 billion would continue to face capital requirements as they are currently structured, while those banks with fewer than $10 billion in assets would face simpler, less stringent requirements.

Figure 1 Minneapolis Plan – capital regime for banks

Source: FRB Minneapolis (2016) Figure 1, and the authors.

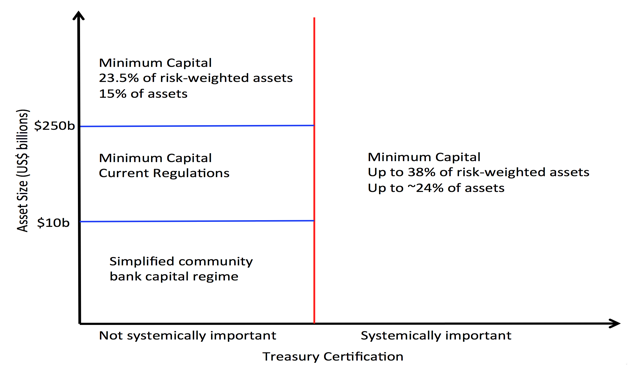

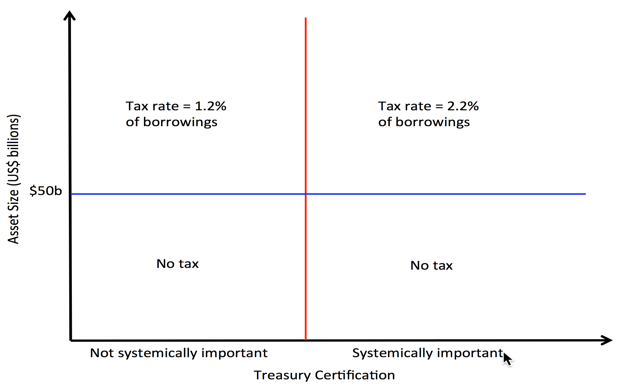

The tax regime for shadow banks is simpler than the capital requirements (see Figure 2). The universe of institutions covered includes the types of nonbank intermediaries monitored by the Financial Stability Board (e.g. Financial Stability Board 2015). The tax applies to firms with more than $50 billion of assets. There are only two tax rates: 1.2% for firms certified by the Treasury Secretary as not systemic; and 2.2% for the rest. This two-tiered tax is intended to mimic the additional funding cost arising from the two-tiered capital requirements for covered banks. A portion of the shadow-banking tax (an estimated 0.4 percentage points according to the Plan) merely offsets the US tax subsidy that permits deduction of interest payments, but not dividends.

Figure 2 Minneapolis Plan – tax regime for shadow banks

Source: FRB Minneapolis (2016) and the authors.

Virtues of the Plan

In addition to its realistic assumptions, the Minneapolis Plan has several other virtues. The first is its clarity in matching objectives with tools. It relies on equity capital, not only as the surest shock absorber in the financial system, but also as a device to induce large banks to shrink, reduce their complexity, and become less interconnected. A covered intermediary funding 38% of risk-weighted assets (or nearly 24% of overall assets) – the long-run default requirement unless the Treasury Secretary declares the bank to no longer be systemic – would have a buffer sufficient to dramatically reduce its chance of failure even under extreme stress.

Second, the Plan anticipates a prime mechanism for its circumvention – the migration of risk from banks to less-regulated shadow banks, some of which already are systemic. It aims to levy the same constraint on the systemic activities of shadow banks that it does on covered banks. Again, the Plan takes a simple approach – its broad tax on the borrowing of shadow banks is designed to mimic the additional funding cost that higher capital standards impose on a covered bank.

Third, unlike some proposals, the Plan acknowledges Dodd-Frank’s continued role in ending TBTF. Dodd-Frank’s stress tests would help verify compliance with capital standards, discourage ‘covered banks’ from loading up on systemic risk, and help identify efforts to conceal risk (say, by shifting it off balance sheet or by using derivatives to create synthetic leverage). Similarly, living wills would still encourage large banks to make themselves simpler and less connected, and facilitate their resolution.

Fourth, by focusing regulatory attention on the largest, most complex, most interconnected institutions in the financial system – as of midyear, the eight US G-SIBS alone held assets worth $10.7 trillion accounting for nearly 70% of all commercial bank assets – and by penalising the most systemic shadow banks through a supplementary tax regime, the Plan would allow regulators to relax the constraints imposed by Dodd-Frank on the vast number of small institutions that pose virtually no threat to the financial system as a whole (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2016c).

Fifth, the Plan exhibits appropriate humility regarding the calibration of its capital requirements and tax rates. Society will benefit from learning by doing, so long as we take account of the financial system’s response to further substantial increases in capital requirements.

Sixth, the Plan requires that the benefits of the new regulatory regime exceed the costs. Accordingly, it does not try to eliminate financial crises, but instead aims to reduce their frequency to an acceptably low level (specifically, once in 100 years).

Finally, the Plan allocates discretionary power over the US financial system where it is most likely to be effective – to the Treasury Secretary. The Secretary can command the resources necessary to judge whether a financial intermediary is systemic and can enforce her decision.

Weaknesses of the Plan

So, where are the weaknesses in the Plan? First, are the thresholds for covered banks ($250 billion of assets) and for assessment of shadow banks ($50 billion of assets) appropriate? Such arbitrary numbers always invite regulatory arbitrage. Second, the list of shadow banks is open to debate. Which types of institutions should be in and which should be out? At the moment, the Plan excludes insurers, despite evidence that some insurers engage extensively in shadow banking (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2016c). Finally, how can the tax on shadow banking be implemented so as to minimise circumvention (say, by an institution shrinking below the minimum asset size to be covered)?

Our bottom line is that, while the Minneapolis Plan needs much further analysis (and probably considerable tinkering with its parameters), the broad design provides a solid basis for legislation that would advance the public goal of making the financial system safe in a cost-effective way. The key is to strengthen the resolve of future policymakers to do what the Federal Reserve could not do in 2008 with AIG – deny emergency credit even in a period of financial distress. By reducing the probability of the politically corrosive bailouts that TBTF engenders, the Plan also would help restore confidence in a critical tenet of capitalism – that risk-takers in the financial system not only profit from success, but also bear the full costs of failure. Absent such confidence, it is entirely possible that the extraordinary benefits of free enterprise and competitive markets will disappear.

Authors’ note: An earlier version of this column appeared on moneyandbanking.com.

References

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2014a) “Living wills or phoenix plans: Making sure banks can rise from their ashes”, moneyandbanking.com, 13 October.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2014b) “Higher capital requirements didn’t slow the economy”, moneyandbanking.com, 15 December.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2015) “Dodd Frank: Five years after”, moneyandbanking.com, 15 June.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2016a) “The scandal is what's legal”, moneyandbanking.com, 8 February.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2016b) “A primer on securities lending”, moneyandbanking.com, 7 November.

Cecchetti, S G and K L Schoenholtz (2016c) “Dodd-Frank, the CHOICE Act and small banks”, moneyandbanking.com, 7 December.

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2016a) Quarterly Bank Profile: Second Quarter 2016, 10(3).

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (2016b) “Global Capital Index”, June 30.

Financial Stability Board (2015) Global shadow banking monitoring report 2015, 12 November.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2016) The Minneapolis Plan to end too big to fail, 16 November.

Endnotes

[1] See the discussion in Cecchetti and Schoenholtz (2014a, 2015, 2016a).