The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak is creating severe health and economic emergencies for Italy and other EU member states. Gathering all the necessary financial resources to fight it without the support from Europe not only would be inefficient, but a social risky bet.

Why will some European countries be able to confront the crisis on their own while others will not? Focusing on the case of Italy, the fundamental reason is pre-existing vulnerabilities, which limit fiscal space and magnify the impact of the economic sudden stop.

1. High public debt. As COVID-19 hit Italy, public debt, d, stood at 136% of GDP, the second highest in the euro area after Greece. Italy’s debt dynamics were already on a knife-edge, stabilising at levels such that even small changes in growth or interest rates could make Italian debt unsustainable.

2. Low growth. In 2019, Italy’s growth rate, g, was 1.2% and prior to the outbreak, the IMF projected Italian growth to be the lowest in the EU over the next five years, with estimated potential growth at just 0.5% (IMF 2020: Art IV consultation).

3. High financing costs and needs. In 2019, Italy’s ‘effective’ interest rate, r, was 2.7%, the highest among the medium and large euro area countries, reflecting the fact that Italy is BBB-rated largely as a result of its high debt, d, and low growth, g. A direct implication is that Italy’s financing costs and needs are very high. Italy’s annual financing costs amount to 3.6% of GDP and its annual gross financing needs (GFNs) are over 25% of GDP.1

These three elements – high d and r, and low g – are the key to Italy’s economic weaknesses. Before the COVID crisis, Italy was the only country of the euro area with (r-g)>0. Hence, its debt will not decrease with time, as it would with (r-g)<0, but must be reduced to arrive to a stable debt/GDP ratio, d*, and a primary balance pb* (the fiscal balance before interest payments) satisfying the public-debt equation: pb*≈(r-g) d*

Other factors should also be accounted for, as either weaknesses or strengths of the Italian economy, such as the following:

- A high primary balance is a strength. Italy has historically had high primary balances (1.7% of GDP in 2019). However, political fragmentation may be an obstacle to maintain a primary balance above 1% of GDP in the future (it should be noted that EU support may be key to maintain the historical Italian consensus). Cautiously, the IMF projects over the medium term a primary balance of 0.9% of GDP.

- More committed investors now compared to the sovereign debt crisis. The ownership of debt remains to a large extent domestic. The good side of this is that domestic investors are less footloose than international investors. Nonresident investors now account for (just under) 30%. In addition, the ECB holds about 28% of Italian debt, it will increase over time, and it will be reinvested for the foreseeable future. This means that the so-called capitulation risk, while present, may be lower than in 2010-13.

- Vulnerable banks. While banks have built sizeable capital and liquidity buffers, many still suffer from low profitability, excess capacity, and high NPLs. The ability of banks to support the economic recovery may be more limited than in other regions.

1. Baseline scenario: Debt sustainable with risks

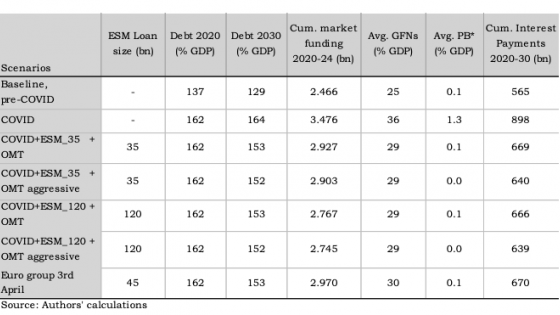

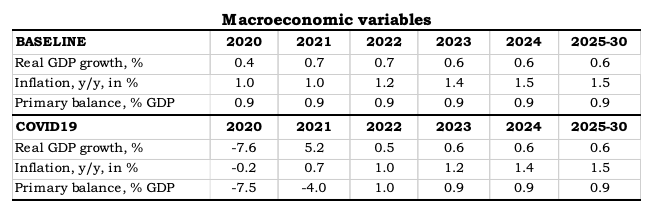

In our baseline scenario there is no COVID-19 crisis. We adopt the same medium-term macroeconomic scenario as the IMF (March 2020, IMF Art.IV). As described in Table 1, we only depart from the IMF’s assumptions on the interest rate path, we project medium-term interest rates based on the benign market conditions prevailing pre-COVID shock. Under these assumptions, Italy’s public debt was sustainable but vulnerable to macroeconomic and market shocks. In addition to the large public debt, debt rollover risk was high, since debt maturities alone over the next four years amounted to €1.83 trillion, roughly the size of Italy’s GDP (Table 2 shows key summary statistics from a debt sustainability under the baseline, COVID-19 stress, and alternative ESM funding scenarios).

Table 1 Macroeconomic and financial scenarios

2. COVID-19 scenario: A very risky path

The Italian government announced in March a series of support measures amounting to €24.7 billion and guarantees amounting to €65 billion, and a second aid package of €25 billion to be approved in April (see Appendix for the details of the measures).

Table 1 shows our macroeconomic scenario under the COVID-19 shock. Real GDP contracts to almost -8% in 2020, bounces back in 2021 to +5%, and converges towards a medium-term growth of 0.6%. The primary deficit rises to 7% of GDP and, once recovered from the COVID shock, gradually improves towards a primary surplus of nearly 1% of GDP.

Table 2 shows that after the COVD-19 shock, public debt jumps to 162% and increases gradually towards 165% over the next ten years. We estimate the debt-stabilising primary balance at 1.3% of GDP over the coming years, up from 0.1% of GDP in the baseline — a very large increase in the required fiscal effort to ensure the sustainability of debt.

The annual gross financing needs (debt maturities, interest payments and primary balance) increase by over 10 percentage points of GDP per year to 36% of GDP. After the shock, the Italian Treasury would need to rollover an additional €670 billion of debt over the next four years.

On its own, Italy could stabilise its debt with a relatively high primary balance, as it has had in its recent history — Italy had sustained primary balances above 1.5% of GDP. However, such extra fiscal effort can be socially very costly in the aftermath of the COVID crisis and possibly endanger the recovery. Instead, using euro area support Italy could put its debt in a clearly manageable path in the medium run, as we show in Table 2. Which form should the financial support of the euro area take?

3. ESM and ECB support: Reinforces debt sustainability

It is critical that the euro area shows its determination, beyond the already expressed support by the ECB, as, fortunately, seems to be the case. A European Recovery Programme will require different instruments to address different needs (firms and workers in distress, health security, etc.) However, there is a crucial need that must be confronted: to make sure that the effort that member states are making to fight, and recover from, the COVID-19 does not become an excessive debt burden or, even worst, another euro debt crisis. To address this, here we evaluate alternatives that combine COVID-related ESM loans and ECB support. We see this as the fastest way to provide low interest funding while the pandemic freezes economic activity.

We evaluate various scenarios (Table 2) which combine different intensities of support by the ESM and the ECB.

On the ESM funds, we consider the following alternatives:

- Loan size. We consider two alternatives: a smaller and larger ESM loan of €35 billion (2% of GDP) and €120 billion (6.5% of GDP), respectively. The smaller loan is in line with the maximum size proposed by the Eurogroup. Both are well within the existing ESM funds of €410 billion.

- Loan interest rate and maturity. We assume a 12-year maturity with a 5-year grace period. We also assume that the ESM maintains a funding strategy with and average maturity between 2 and 3 years. We assume a 10 basis point spread charged on its standard loans (Table 1 shows the assumptions on the ESM funding rates).

In addition, we also assume that the ECB’s asset purchase programmes continue as planned and that the ECB’s OMT is activated. On the back of ESM support and ECB’s asset purchases, we assume that Italian yields are brought back to levels similar to the baseline (pre-COVID-19). In a separate scenario, we also consider a more aggressive OMT programme, where 1- to 3-year bond yields are compressed towards those of France.

A note of caution. Our assumption regarding the prevailing market rates does not change in a scenario with a big or a small ESM loan; in both cases we use the no-stress, pre-COVID-19 rates. We could have assumed lower medium-term market rates in the scenario with bigger ESM loan. Needless to say, this would make the outcome of the debt sustainability analysis even more favourable toward the bigger size programme.

The upshot of these scenarios is that Italy’s debt dynamics improve markedly and become sustainable and, in particular, that the reduction of gross financial needs and interest payments plays a crucial role.

- Public debt on decreasing path. Debt/GDP falls by 10 percentage points of GDP from its peak of 162% in 2020 to 152% in 2030. Extending our medium-term macroeconomic assumptions into the longer term would show a further reduction in Italy’s debt/GDP.

- Fiscal effort back to normal. The annual fiscal effort needed to stabilise public debt is brought back to a level similar to the pre-COVID19 shock: the debt-stabilising primary balance (PB*) drops by 1.4 percentage points of GDP relative to the stress scenario without support.

- GFNs considerably lower. Annual gross financing needs drop by over 7 percentage points of GDP per year, relative to a scenario without European support.

- Debt issuance at manageable levels for the Italian Treasury. The cumulative market financing needs over the near term (2020-25) would drop by €730 billion (about 40% of GDP) relative to a scenario without ESM support. This massive improvement substantially reduces the costs of the Treasury monthly issuance.

- Stronger ESM and ECB support is preferable. There are differences among the level of ESM and ECB support. Comparing the most supportive scenario (€120 billion loan and aggressive ECB’s OMT) to the least supportive (€35 billion loan and less aggressive ECB’s OMT), the former delivers €182 billion (10% of GDP) less market funding needs than the latter.

- Interest payments drop. Under the most favourable scenario, with strong ESM and ECB support, the cumulative interest payments 2020-30 fall by about €260 billion, over 14 percentage points of (2019) GDP relative to a scenario without European support.

Table 2 DSA scenarios: Main results

In addition to these results, we also analysed an ESM scenario based on the information leaked by the press on 3 April regarding the latest Eurogroup proposal (negotiations are ongoing). The proposal reported by the media would entail a €45 billion loan at 5-year maturity. The upshot of that scenario is that the results would be very broadly similar to the €35 billion scenario analysed here. However, the cumulative market financing needs by the Treasury over the next years (2020-24) would increase by over €200 billion (12% of GDP) as the loan maturity considered in the Eurogroup proposal is only 5-year versus 12-year maturity and 5-year grace-period assumed in our scenarios.

4. What are the differences between Coronabonds, ESM loans and ECB purchases of sovereign bonds?

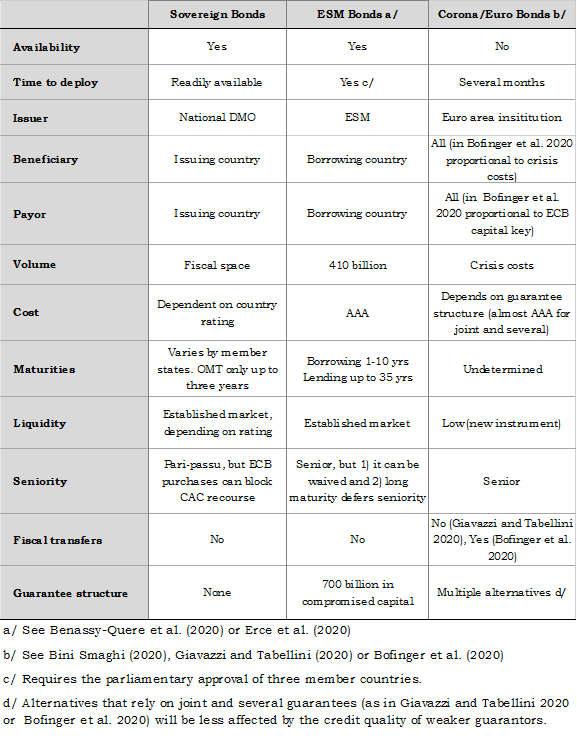

What shape could euro area coordinated fiscal support take? While following the last Eurogroup meeting, the use of ESM resources appears to be the preferred alternative for northern European countries, a variety of alternatives are currently on the table. In this section we explain what differentiates (and what does not differentiate) Coronabonds and similar forms of common issuance (i.e. the European Recovery Fund) from an ESM loan and from maintaining the status quo, in which support is obtained using sovereign bond issuance and ECB purchases in secondary markets.

To facilitate the comparison, Table 3 summarises the main aspects of each funding alternative. First, ESM funding could be available rapidly. The ESM is already fully operational and has €410 of available funds, which (with political will) could be tapped without delays. In contrast, Coronabonds, even if there would be political will, would require a process of design – including legal aspects – and ratification that could last for months. It should be noted that the ESM alternative involves only euro area countries, while SURE or measures involving the EIB would be at the EU level.

In addition, funding through the ESM presents some financial advantages. The ESM can pass on its low (AAA-rating) funding rates at an almost zero spread and it is more legally secure (Pröbstl 2020). Currently, even under the ECB’s PEPP program, there is a 150 basis point spread between a 7-year BTP and a German Bund (7-year is roughly Italy’s average debt maturity). An alternative common issuance instrument is likely to have a strong rating. Whether it would reach the level of the ESM, where the capital structure includes committed capital from high rating stockholders covering the maximum lending capacity, would depend on the agreed guarantee structure.

Under a joint guarantee structure, the rating of the new instrument would be similar to AAA. Instead, guarantees according to the ECB capital key could imply a lower credit quality of the guarantee, and thus more expensive borrowing. A new common instrument, even if designed to be AAA, would lack the liquidity of a well-established market of ESM bonds. This comparatively lower liquidity is likely to translate into more expensive and less effective financing terms.

Second, ESM loans perform a powerful maturity transformation for member states. The ESM funds itself on average between two and three years (at negative yields for an AAA-rated issuer) and provides long-term loans to member states (up to 35 years). The proposal currently under discussion by the Euro group foregoes this important benefit by proposing a maturity of the ESM loans not higher than five years.

Last, but not least, by replacing issuance by domestic DMOs, ESM loans reduce the risk of tensions on primary markets by making lighter the (already very heavy) debt issuance of Italian Treasury.

On the negative side, the conditionality accompanying an ESM loan can be a deterrent for governments, particularly if, as in the case of Italy, they are under political pressure. Against this argument, it seems that the Eurogroup is ready to agree on access to ESM without strings attached if the funding is for the COVID emergency.2

The seniority of ESM loans is also seen by some as a potential problem. We believe this risk to be manageable for the three following reasons. First, the size of the ESM loan would be small relative to the stock of debt. Second, seniority could be waived, as with the ESM programme to Spain in 2012. Third, the long maturity of ESM loans dilutes/defers any market concern about seniority (Ghezzi 2012a).

Closely related to the seniority issue are the limits set by the ECB for its asset purchase programmes. In particular, the purchase of more ESM bonds and less national government bonds could be beneficial for member states and the euro area as a whole. Financing euro area countries through ESM bonds reduces the likelihood that the ECB will hit the capital key limit for the borrowing country.3

Table 3 Principal features of different funding strategies

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 has changed the lives of European citizens, at least temporarily, and there is widespread consensus that how this crisis is resolved will mark the evolution of the EU and the euro area. Member countries have taken individual initiatives first, but the virus has no nationality and European action is needed. After the ECB took the lead, the European Commission and the other European institutions – in particular, the ESM and the EIB – are now reacting to the call, which hopefully will become “our Marshall Plan” as Mário Centeno, President of the Eurogroup, said (El País, 4 April 2020). Support will take different forms and use different instruments, with a common goal: to avoid that coronavirus overburdening any European country or region.

Preventing that the COVID-generated sovereign debt becomes an unnecessary – crisis-ridden – burden must be a central part of this programme. The announced EIB guarantees and the SURE unemployment re-insurance will also help countries. However, these measures are not a supplement, but a complement, to the already feasible ESM financing discussed here. In this column we have exemplified how combinations of COVID-conditional ESM loans and ECB interventions can be used to support Italy, one of the most COVID-stressed euro area countries.

There is the view that the ESM intervention should be saved for a later day, in case that a debt crisis really emerges. However, the fact that the ESM was originally designed as crisis resolution mechanism, cannot mean that it should not be used as an effective crisis prevention mechanism, when it can. In the same way that countries that have not been heavily hit with by the coronavirus should not procrastinate over their preventive testing, preventive economic measures should be resolute. ESM and ECB support would reinforce Italy’s public debt sustainability, support confidence, and fundamentally alleviate the market funding needs over the next years of the Italian Treasury.

References

Bénassy-Quéré, A, A Boot, A Fatás, M Fratzscher, C Fuest, F Giavazzi, R Marimon, P Martin, J Pisani-Ferry, L Reichlin, D Schoenmaker, P Teles and B Weder di Mauro (2020), “COVID-19: A proposal for a Covid Credit Line”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Bini Smaghi, L (2020), “Corona bonds – great idea but complicated in reality”, VoxEU.org, 28 March.

Bofinger, P, S Dulline, G Felbermayr, M Huther, M Schularick, J Sudekum and C Trebesh (2020), “To avoid economic disaster, Europe must demonstrate financial solidarity”, 21 March.

Erce, A, A García Pascual and T Roldan (2020),” The ESM must help against the pandemic: The case of Spain”, VoxEU.org, 25 March.

Ghezzi, P (2012a), “Debt seniority and the Spanish bailout”, VoxEU.org, 23 June 2012.

Ghezzi, P (2012b), “ECB limited and conditional lending is not 'what it takes'”, VoxEU.org, 19 August.

Giavazzi, F and G Tabellini (2020), “Covid Perpetual Eurobonds: Jointly guaranteed and supported by the ECB”, VoxEU.org, 24 March.

Pröbstl, J (2020), ESM loans and Coronabonds: A legal analysis from the German perspective”, VoxEU.org, 4 April.

Appendix. Italian fiscal package

Here are the details of the Italian government fiscal support plan:

(i) Law Decree n. 9/2020 of 2nd March, containing measures for families, workers and business.

(ii) Law Decree n. 14/2020 of 9th March (strengthening the healthcare system and civil protection).

(iii) Law Decree n. 18/2020 of 17th of March (“Cura Italia” decree).

(iv) Additionally, various Decrees of the President of the Council of Ministers and Civil Protection ordinances were used to enact measures for the containment and management of the emergency.

From the summary presented by the Ministry of Finance on their webpage, the measures taken, presented along with the amounts of funding or guaranteeing involved, are the following:

- Strengthening the National Health Care System and the Civil Protection Department (3.2 billion)

- Preserving employment levels and incomes (10.3 billion)

- Pumping liquidity to help businesses and households (5.1 billion + 60.5 billion in guarantees).

- Suspending tax payments and providing tax incentives for workers and businesses (1.6 billion)

- Additional measures to support central and local public administrations, including municipalities, are worth €45.5 billion.

This adds to around €24.7 billion direct measures and above €60 billion in guarantees. In addition, new measures have been announced by PM Conte for April 2020, amounting to €25billion.

Endnotes

1 In recent years, the Italian Treasury increased the average duration of public debt to nearly 7.5 years. Although this reduces rollover needs, this positive effect was mitigated by higher interest payments.

2 Benassy-Quere et al. (2020) and Erce et al (2020) discuss how to design COVID-related light conditionality.

3 Euro area sovereign bonds contain two-limb aggregation clauses. ECB purchases can reduce their effectiveness by diluting the bonds for which purchases are relatively smaller. This could disrupt liquidity on primary markets at times of distress (Ghez