The amount of financial resources needed to fight the pandemic is so large that most member states will need a backstop from Europe. There have been proposals involving Eurobonds and helicopter money — these would work and may eventually be implemented. However, a fully operational and speedy solution is needed now. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) lending toolbox is available, has funds and is scalable. In this column, we operationalise the proposal by Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2020a, 2020b) to create a “Covid credit line in the ESM with allocation across member states”. We evaluate three funding alternatives using the existing ESM toolbox. We use Spain as a case study, but similar results would apply to a broad range of euro area countries. We calibrate a combination of a large, long-maturity ESM loan and a near zero interest rate that delivers a prudent gross-financing-needs path, a fiscal effort within reach, and sustainable public debt dynamics.

- The Spanish government has put forward a plan that amounts to €200 billion (16.5% of GDP) including transfers and government guarantees, which will mostly be called in. Funding such a package in the markets would be challenging for the Spanish Treasury. Gross financing needs would increase to about 30% of GDP per year for the foreseeable future and public debt would reach almost 140% of GDP by 2030.

- Using a debt sustainability framework, we show how an ESM loan, without a spread and a smoothed repayment schedule, would stabilise public debt-to-GDP at 125% of GDP, and gross financing needs would remain at less than 20% of GDP per year.

- Lower interest rates under the ESM programme could help Spain save around €150 billion in interest payments cumulatively between 2020 and 2030. ESM support would also reduce the fiscal effort needed to stabilise public debt. The fiscal effort could be reduced to a level similar to the baseline scenario without the COVID-19 shock.

- ESM support, especially if coming through a precautionary line or a standard programme (with light conditionality), would be most effective if provided with reduced margins (as with Ireland and Portugal in 2011) and financed with short maturities. They would also allow the activation of ECB’s OMT programme.

- In sum, the combination of a bold ESM and ECB support solidifies sustainability after the COVID-19 shock, and can do the same for more fragile member states.

A public backstop against the sudden stop

Europe has become the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Spanish Health Ministry, by 22 March, Spain was up to 28,572 identified COVID-19 cases and 1,720 dead, lying just behind Italy, China and Iran in coronavirus deaths worldwide. In addition to the rapid contagion of the virus and high fatality rate, economic activity is coming to a sudden stop. We don’t know yet how long this sudden stop will last. Two, three months, perhaps more? Global markets have experienced a sell off over the last two weeks not seen in recent history. Spanish sovereign spreads shot up by 200 basis points since the outbreak of the crisis. ECB’s €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) is keeping spreads in check for now.

There is huge uncertainty about the future path of the pandemic, let alone the impact on the economy. Let’s assume that some of the service sectors badly hit by the virus come to a complete sudden stop and some other sectors operate at less than full capacity for four months. The aggregate impact using a gross value-added approach could be close to 40-50% loss in activity in March and April and about 20-30% in May and June. We assume that in July, economic activity resumes but remains sluggish.

The impact on aggregate GDP from the disruption in domestic and global activity would be in the order of 10-12% (without policy support). And most of this loss in economic activity would not be recovered in the future – restaurant and hotel visits will not double in the future to make up for those lost over March, April, May, and beyond.

The contraction in economic activity does not have to be double digits. In fact, we believe it won’t. Public policy will play a crucial role to mitigate the impact on economic activity. The very large but temporary transfers to households and firms could reach 10 percentage points of GDP. A portion of the support to firms is likely to be in the form of loans and guarantees (i.e. not adding to the deficit but adding to the stock of debt, including guarantees if they are called).

In addition to these credit policies, the overall deficit will rise with: (1) automatic stabilisers; (2) the increase in financing costs (as the stock of public debt in 2019 was at nearly 100% of GDP); and (3) the starting point for the overall deficit in 2020 at 2.5% of GDP. All in, a rough estimate of the 2020 deficit could reach up to 13% of GDP.

Following the example of other countries, the Spanish government approved last week a fiscal package that amounts to €200 billion (16.5% of GDP). It includes direct transfers of €17 billion, government guarantees of €100 billion and a commitment through the private sector of a further €83 billion in guarantees, which we believe will eventually turn into government guarantees.

Given the nature of the sudden stop and the sectors hit by the pandemic, for the purpose of the analysis we assume that all the guarantees will actually be called in. While this might seem a strong assumption regarding the guarantees, we believe it is prudent to assume that those liabilities would come back to the sovereign as COVID-19 hits hard households, firms and the financial sector (high NPLs and low credit). Those will be our working assumptions when we turn next to study the financing of this plan in the following sections.

How to fund the anti-COVID package

Overall, the 2020 deficit will most likely be the highest single-year deficit in modern history, even if lower than the cumulative multi-year deficit that resulted from the sovereign debt crisis. In 2012 Spain had to turn to the ESM to help fund its fiscal support programme. The obvious question now is: if conditions worsen again, can Spain fund its anti-COVID package without European support?

To answer that question, we need to examine how different COVID-19 macro scenarios affect public debt dynamics and gross financing needs (GFNs). The upshot of our debt-sustainability analysis (DSA) is that by 2021, public debt will jump up to over 120% of GDP and would continue rising to reach nearly 140% by 2030 (the next section shows the DSA and gross financing needs under alternative scenarios). In order to avoid falling back into the perverse market dynamics of the sovereign debt crisis, it would be essential to keep financing costs in check. A few basis points make a big difference for the future interest rate bill, gross funding needs and debt dynamics, especially when the public debt ratio is so high.

The algebra behind the fiscal effort needed to stabilise public debt dynamics is all too well known. It is essentially driven by three variables, “(r-g)*d”, where

r is the effective interest rate on public debt, currently at about 2.7%;

g is nominal GDP growth, which will be close to -4% in 2020 after the shock; and

d is debt/GDP, which stands at 97%.

As Blanchard (2019) has rightly pointed out, even for Italy under the interest rate of an AAA-rated issuer — at negative funding rates — the increase in public debt would not be an issue. But for Spain, with a high public debt and deficit and double-digit unemployment levels, global investors will likely demand higher interest rates. The yield on the 10-year Spanish sovereign bonds jumped in the second week of March to well over 2% from 0.2% a few weeks earlier.

Thanks to the latest ECB announcement of the PEPP, government bond yields have compressed again but they are not back to pre-crisis levels. The ECB’s asset purchase programmes now include: €750 billion (PEPP), €120 billion (announced at the 12 March ECB policy meeting) and the ongoing monthly purchases of €20 billion. Given Spain’s capital key of near 10%, this means that there is around €100 billion in fire power available to buy Spanish public and private debt. This will help the Spanish Treasury with its pre-COVID-19 gross funding needs of over €200 billion for 2020.

The trouble is that gross funding needs would increase materially with the COVID-19 fiscal package, and so will public debt. Under elevated uncertainty and high risk-aversion, the combination of fragile debt dynamics and elevated funding needs can become difficult to manage. We discuss next the pre- and post-COVID shock scenarios with and without ESM support.

Adverse debt dynamics after COVID-19 without European support

Spain ended 2019 with public debt of 97% of GDP and a fiscal deficit of 2.5% of GDP. Under our medium-term macro scenario, the debt-stabilising primary balance for 2021-30 (average) is -0.7% of GDP: the average growth, g, is 2.5%; the average funding cost, r, is 1.75%; and public debt, d, stabilises around 100%. Basically, this is consistent with the annual fiscal effort that the Spanish government was realistically able to deliver over this period. The average gross financing needs (GFN) ranged between 17% and 20% of GDP per year, which seemed manageable.

The COVID-19 shock has triggered an unprecedented fiscal package of €200 billion. As a result, we estimate public debt in 2021 will surpass 120% of GDP, and will keep on rising to reach 137% of GDP by 2030. GFNs through 2030 average 29% of GDP per year, i.e. 10 percentage points of GDP higher than in the pre-pandemic scenario. In order to be able to evaluate the situation if the spreads were to creep back to the levels seen last week, we have assumed that marginal interest rates remain stressed for two years after the shock, but thereafter move back to those in the baseline scenario plus 50 basis points (we maintain a higher spread relative to the baseline to reflect the market cost of higher public debt). As a result, by 2030, the average funding cost (on all stock of debt) is 120 basis points higher than in the scenario prior to COVID-19.

In this stressed scenario, the COVID-19 shock pushes debt dynamics over the limits that standard DSA frameworks would consider sustainable. The markets very likely would accelerate the adverse dynamics by demanding a higher country risk premium, which would turn into an even more adverse trajectory for the debt dynamics and GFNs. Spain would be in a ‘bad equilibrium’ that becomes self-feeding: the higher interest rate on public debt would not be seen by investors as an attractive high return on Spanish Bonos, but rather as too high of a country risk, demanding an even higher interest rate, which in turn worsens the fiscal dynamics.

The ESM can overturn adverse debt dynamics

Critically, the ESM can provide financial assistance to Spain at lower financing costs than the market. Funding from the ESM is generally at 10 basis points over the ESM’s own funding cost (currently negative).1 In addition to its lower cost for Spain, the standard ESM programme also embeds an important advantage. Once a member state activates such programme with explicit conditionality, the ECB can unlock purchases of the country’s public debt through its Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme. This would further compress the funding costs for Spanish sovereign debt. The activation of an OMT programme can work as setting a ‘yield curve control’ programme on the Spanish yield curve.

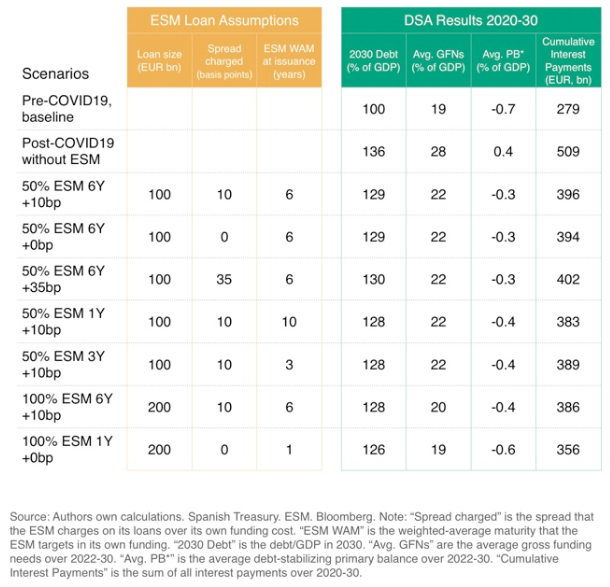

Table 1 summarises ESM financing scenarios and their impact on debt sustainability. Table 2 provides the detailed macroeconomic framework of our main scenarios.

Table 1 Debt sustainability simulations

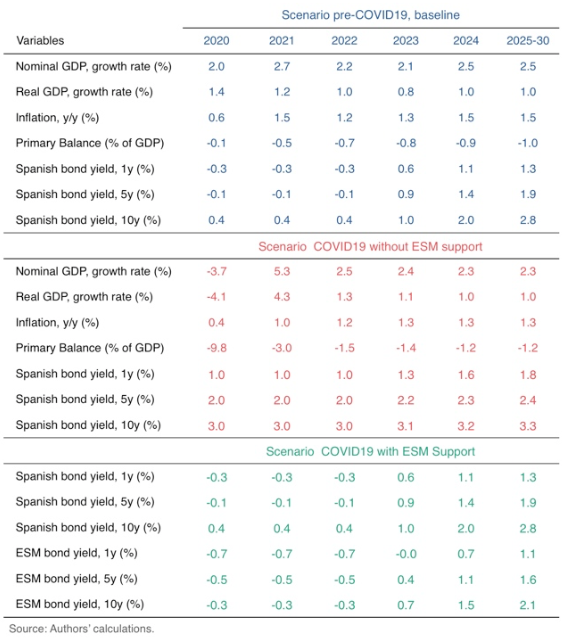

Table 2 Macroeconomic and financial scenarios

The different scenarios are organised around three important parameters/assumptions:

- The size of the ESM loan to Spain, which we assume would be between €100 billion and €200 billion (i.e. 50% and 100% of the 2020 fiscal support package, respectively). Our baseline is that Spain would receive around €100 billion. A larger package would be more beneficial for Spain but would leave less resources for other member states in need (the ESM currently has a €410 billion lending capacity).2

- The spread over the funding rate charged by ESM to cover ESM costs, which we allow to vary between 0 and 35 basis points to represent the borrowing cost under various existing ESM lending facilities. Ten basis points is the spread charged under standard ESM programs, and 35 basis points is the spread charged on the ECCL facility. In turn, a zero spread is currently charged to Ireland and Portugal on their loans with the EFSF. We assume that the ESM funds itself at about 8-10 basis points over the German Bund curve.

- The weighted-average maturity (WAM) targeted by the ESM in its own funding strategy in the markets. We experiment with a WAM between one and six years. Currently the ESM targets a WAM of two to three years.

We do not experiment with the maturity of the ESM loan, which we set to be identical to the one Spain received in 2012 (12-year maturity with a 5-year grace period). Neither have we experimented with the issuance strategy of the Spanish Treasury, which we set to replicate that observed in practice. Thus, we set WAM at issuance to be six and a half years when stress is lower, and four years when stress is higher. In all our scenarios, WAM at issuance converges to five and half years by 2024 and stays there.

Table 1 also shows four key summary statistics extracted from the DSA analysis conducted for each scenario:

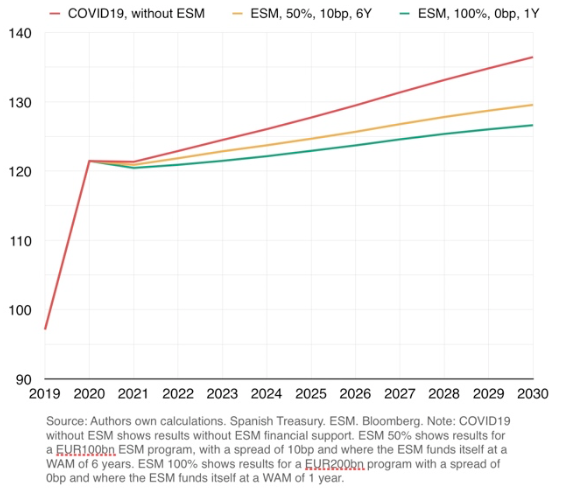

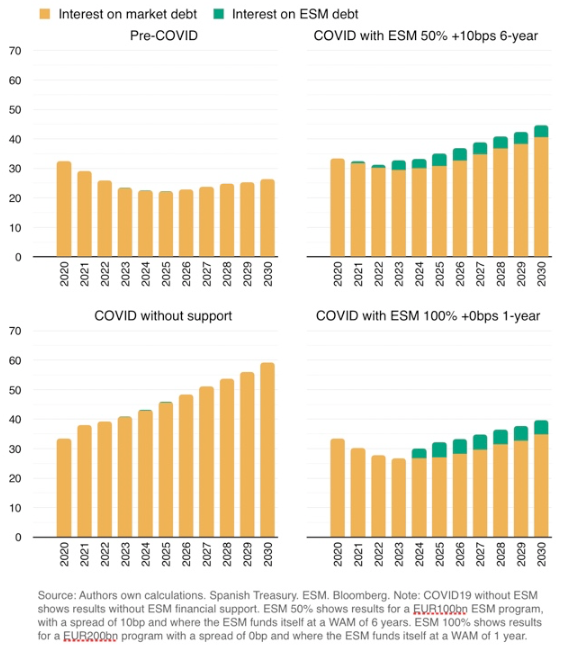

- Public debt/GDP in 2030. It ranges between 100% of GDP in the baseline without the COVID-19 shock and 136% in the post-COVID-19 without any ESM support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Public debt simulations (% of GDP)

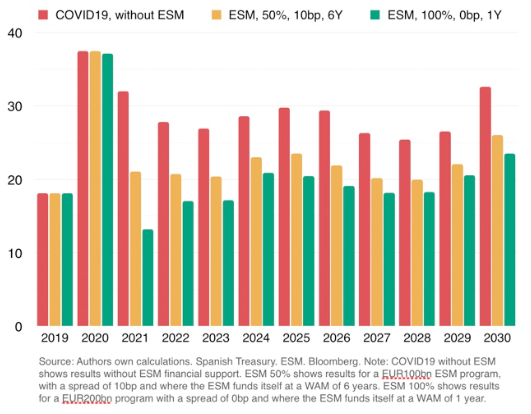

- Average gross financing needs to GDP (GFN/GDP) for the period 2022-30, it leaves out 2020 and 2021 as the large 2020 shock to the fiscal variables and to GDP distort the picture, and we want to capture the medium-term dynamics.

- Average debt-stabilising primary balance to GDP (PB*/GDP) for 2022-30. A higher value denotes a larger fiscal effort needed to stabilise public debt to GDP. Before the COVID-19 shock, the average PB*/GDP was -0.7%. This means that if the public sector were to run a primary deficit of less than 0.7% of GDP, public debt to GDP would be on a descending trend. The highest value (a primary surplus of +0.4% of GDP) is under the COVID-19 shock without ESM support.

- Cumulative interest payments under each scenario. They range between €509 billion (post-shock) and €279 billion (without the COVID shock); in other words, if the Spanish Treasury were to fund the fiscal package in the markets, the cumulative financial costs of the package over the medium term (2020-2030) would be €230 billion. Figure 2 compares the time profile of private and official interest payments for different scenarios, and exemplifies the extent to which AAA-financing can avoid snow-balling interest payments.

Figure 2 Interest on debt (%)

The fundamental takeaway from these scenarios is that, if stress were to resurface, ESM support would fundamentally change the financing conditions for Spain. It would make debt dynamics sustainable with high probability. In particular:

- ESM support makes a big difference in reducing financing costs. The cumulative interest rates payments under the best of all financing scenarios (last row in Table 1) would save Spain over €150 billion – over 12% of 2019 GDP in interest payments!

- ESM support reduces significantly the fiscal effort needed to stabilise or reduce the public debt ratio. In fact, under some of the ESM funding scenarios, the fiscal effort (measured as the average debt stabilising primary balance) would be similar to the baseline scenario without the COVID-19 shock (i.e. -0.6% vs -0.7% of GDP respectively). We are conservative in our assumptions and have assumed a primary deficit in the medium term of 1.2% of GDP. In fact, we believe Spain could do better than that. It should be able to deliver a primary balance close to zero or below -0.6% of GDP (i.e. the debt-stabilising level under the programme).

- ESM support would keep gross financing needs per year at a level (in terms of GDP) similar to the pre-shock baseline of 19% of GDP (see Figure 3).

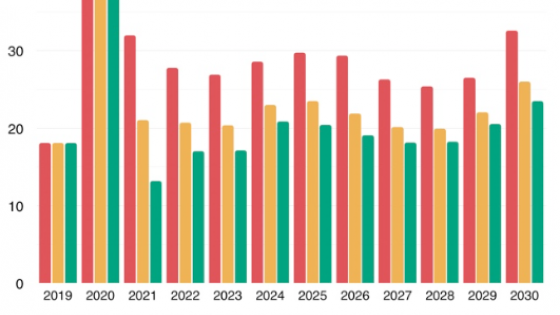

Figure 3 Gross financing needs (% of GDP)

The ESM applies a spread over the funding costs to its loans. This spread differs across instruments to reflect varying risk profiles of each instrument. For standard loans, the margin is 10 basis points. A higher margin of 30 basis points will be applied to facilities for the recapitalisation of financial institutions. Finally, for precautionary credit lines the margin applied is of 35 basis points. As we have shown in the DSA simulation exercises, even a small reduction in the spread from 10 basis points to 0 basis points makes a big difference over the medium term on interest savings. Thus, ideally, the ESM should eliminate the margin over funding costs charged to borrowing countries. This is what the European Financial Stability Facility did for Greece, Ireland and Portugal in the worst of the crises.

How to overcome ESM institutional constraints

A standard ESM programme with COVID-focused conditionality

Borrowing at ESM financial terms would be a solution to Spain’s public debt sustainability. There are, however, some hurdles to a large ESM support.

Standard programmes require a preparation of a macroeconomic framework and a number of risk evaluations by the European Commission, the ECB and the ESM. Euro area member states in need of financial assistance submit an application to the ESM Board of Governors (Article 13, ESM Treaty). Once such a request has been received, it is assessed by the Commission, the ECB and the ESM. This assessment, which includes a DSA, is likely to be approved for a country such as Spain.3

Given the nature of the current shock, to speed up the European policy reaction, COVID-related ESM programmes could be very lean. Essentially, it would make sense to avoid controversial tests like the debt sustainability analysis (DSA) framework, and introduce conditionality that is exclusively related to the COVID-19 crisis.4

The procedure to approve such a programme would be leaner than that required to modify the lending toolbox, as envisaged in other proposals (e.g. Gourinchas 2020). Given that the delivery of a loan always requires parliamentary approval by some members states, where the national parliament has the legal right to vote on ESM lending (Germany, the Netherlands and Finland), time is of the essence. Creating a new lending instruments can be agreed by the ESM’s Board of Directors, but this would significantly protract the process.

As Wyplosz (2020) rightly argues, this is an important drawback for any proposal that intends to make use of ESM funds, given that national politics are likely to be tense in the coming weeks and months. However, we think stigma should not be an issue if conditionality is focused on solving the COVID-19 crisis. If policymakers in countries in need of support become concerned also about conditionality through enhanced surveillance, they risk prompting northern policymakers to dig into their trenches and insist on “no pain, no gain”.5 In sum, we see scope for agreement on COVID conditionality in exchange for ‘symbolic’ surveillance to ensure that resources are focused on COVID-19 needs.

Precautionary facilities: ECCL and PCCL

If agreement to such streamlined conditionality within a standard ESM programme cannot be reached, countries could alternatively try to access the precautionary facilities. Currently, there are two types of precautionary facilities: a Precautionary Conditioned Credit Line (PCCL) and an Enhanced Conditions Credit Line (ECCL). Both lines can be drawn using a loan or direct purchases on the primary market. Compared with standard programmes, these programmes’ conditionality is to a greater extent ex ante, as access requires pre-qualification. Spain could pre-qualify for an ECCL.

Access to a PCCL is based on pre-established conditions, which limit access to countries which remain fundamentally sound. The pre-qualification conditions include: (i) respect for commitments under the Stability and Growth Pact (countries under excessive deficit procedure can access PCCL provided the debtor follows the Council recommendation); (ii) sustainable general government debt; (iii) respect commitments under the excessive imbalance procedure (countries under this procedure can access a PCCL if they remain committed to addressing the imbalances identified by the Council); (iv) a track record of access to international capital markets on reasonable terms, (v) a sustainable external position; and (vi) the absence of systemic bank solvency problems. Countries that do not fulfil all conditions to access PCCL, but whose fundamentals remain strong, can still access an ECCL. In such cases, the country accessing the ECCL must adopt corrective measures aimed at addressing its weaknesses and avoiding any future market access problems, while continuously respecting the eligibility criteria which were considered met when the PCCL was granted.

There is no guidance as regards to how large the immediate amount should be. The guidelines for the ECCL include no limit on access or maturities (whatever works politically).6 This implies that the ECCL can, in principle, deliver the same amount and tranching as a normal loan, but subject to quarterly monitoring under enhanced surveillance. Conditionality could be more focused on addressing identified weaknesses, which could be pandemic measures now. But the availability only for one year seems to be an important constraint. An important drawback is that access to the ECCL has a cost of 35 basis points over the cost of funding, plus an upfront fee of 10 basis points on the immediately available tranche and 50 basis points on each actual disbursement (net of fees already paid).

Another potential problem of this approach is that, as in the case of standard ESM loans, they require parliamentary procedures in some member countries whose electorates may see such provision of soft financing with concern.

On the positive side, access through an ECCL can be achieved fast, even if smaller initially, and scalability is unlimited. The ECCL could be applied flexibly in current context, with focused conditionality. Moreover, some changes in pricing, similar to those that European Financial Stability Facility granted to Ireland, Portugal and Greece, could be considered. This would make the loans less onerous, while guaranteeing that all the costs associated with it are covered by the receiving country. Importantly, the ECCL could also open the door to OMT operations by the ECB. According to the OMT technical guidelines, however, access can only happen through a precautionary programme (an Enhanced Conditions Credit Line) provided that the ECCL allows for the possibility of ESM primary market purchases.7

The indirect bank recapitalisation facility

Finally, countries could resort to a facility for the indirect recapitalisation of the banking system, like the one Spain received in 2012. This would allow to design a loan with the specific target of making sure that banks have sufficient capital to write down missed payments by the private sector as these happen. Effectively, the funds would be used to help banks cure non-performing loans (NPLs) using capital as NPLs appear.

A major drawback of the indirect bank recapitalisation facility is that such route would not allow countries to request the ECB to activate OMT. Similar to standard programmes, these programmes require parliamentary approval by some member states. The fact that the facility does not unlock OMT may serve to convince politicians in northern Europe concerned with providing what they consider too much risk-sharing.

Conclusions

Europe is pondering how to best support its member states in their fight against COVID-19. There have been some proposals put forward to backstop member states own efforts including proposals for the EIB, new Coronabonds, and helicopter money (see Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020 for an overview of these proposals). We think there are merits in them all. The challenge, however, is that the economy is in a sudden stop and time is of the essence. The key advantages of using the ESM’s lending toolbox are that it is already operational, has funds, it is scalable and speedier.

In this column, we operationalise the proposal by Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2020b). We have calibrated the size and financial conditions of an ESM programme that would work for Spain. It would solidify the sustainability of debt dynamics. As our simulations have shown, the size and financial conditions of the ESM loan can make a substantial difference in terms of interest payments, gross financing needs, fiscal effort required and public debt dynamics.

While the war-chest of the ESM, with current subscribed capital of over €700 billion and ability to lend €410 billion of funds, is large, it may not be sufficient for the scale of funding needs generated by the COVID-19 shock. Italy and Spain alone could use up all available funds. Therefore, a top-up would be recommendable. Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2020b) discuss how to boost the ESM lending capacity beyond the current level.

References

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (eds) (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, R Marimon, J Pisani-Ferry, L Reichlin, D Schoenmaker and B Weder di Mauro (2020a), “COVID-19: Europe needs a catastrophe relief plan”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, A Boot, A Fatás, M Fratzscher, C Fuest, F Giavazzi, R Marimon, P Martin, J Pisani-Ferry, L Reichlin, D Schoenmaker, P Teles and B Weder di Mauro (2020b), “COVID-19: A proposal for a Covid Credit Line”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Blanchard, O (2019), "Public Debt and Low Interest Rates", American Economic Review 109(4): 1197-1229.

Gourinchas, P-O (2020), “Flattening the Pandemic and Recession Curves”, 13 March 2020.

Wyplosz C (2020), “So far, so good: And now don't be afraid of moral hazard” in R Baldwin and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Endnotes

1 This excludes various fees.

2 In their corona credit line proposal, Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2020b) argue that rising the volume of ESM bonds would have the added benefit of stabilizing the financial sector.

3 As a general rule, if the DSA does not show debt to be sustainable, the ESM cannot lend; however, during the euro area crisis this rule was bent given systemic concerns. At pre-pandemic conditions Spain would be considered sustainable (see our baseline scenario).

4 A dedicated, fast-track Corona Credit Line with a long duration, access conditions and ex post conditionality has been proposed by Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2020b).

5 Moreover, decision making takes place on an intergovernmental basis, with each finance minister possessing either one vote or (on matters concerning ESM capital) a vote weighted according to the capital contribution of his/her member state. Most decisions require unanimity, while decisions on capital require a majority of weighted votes. Emergency decisions are made by a qualified majority of 85% of voting members. This grants three countries (Germany, France and Italy) veto powers over qualified majority decisions.

6 In the revised version of the ESM Treaty that is currently being blocked by Italy, a maturity limit of five years would be introduced to the precautionary facilities.

7 According to the guideline for primary market purchases, these can be conducted both in auctions and syndicated transactions, at market prices and not absorb more than half of the issuance. This proportion can increase if market bids at acceptable prices or the order book are insufficient to ensure that at least half of the originally targeted amount is sold.The bonds purchased can be sold to mitigate the risk of realizing a loss.