Coming of age: EMU@20

Flashback to January 1999. On 2 May 1998, European leaders agree to start the third and ultimate stage of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) on 1 January 1999. As of 1999, the exchange rates towards the common currency are fixed and the ECB becomes responsible for the monetary policy of a currency union made up of eleven countries and 293 million people. Three years later, the first euro coins and banknotes enter in circulation. The culmination of decades of European economic integration, the euro represents a historic milestone and much more than a monetary reform.

Fast-forward to January 2019. Nineteen countries belong to the euro area with a total population of 340 million. The euro has become the second currency used in world markets under any metric.

In spite of the existential crisis in 2011-13, membership to the euro area has continued to grow. In its short life span, the euro has become an anchor of economic and financial integration. In late 2018, the Eurobarometer survey (Eurobarometer 2018) showed that around two-thirds (64%) of euro area citizens think that having the euro is a good thing for their country and about three quarters (74%) think that having the euro is a good thing for the EU, the highest level since the question was first asked in 2004. At the same time, more than two-thirds (69%) in the euro area also think that there should be more economic policy coordination.

The 20th anniversary provides a good occasion to reflect on what the EMU has achieved and what remains to be done. This requires first recalling the initial objectives set for the euro and how these have changed over time, notably due to the weaknesses which came to the fore throughout the recent crisis. This also puts into question the policy taken during the crisis and the priorities going forward.

The Maastricht assignment

The original motivations for creating a common currency in Europe were both economic and political in nature. These are rooted in the collapse of the Bretton Woods world in the 1970s. From an economic standpoint, the common currency was considered a necessary complement to the Single Market that would remove exchange rate risks and conversion costs. As early as June 1982, Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa identified an "impossible quartet": free capital movements, free trade, and exchange rate stability are jointly incompatible with independent national monetary policies. The Delors report (Delors 1989) laid down the operational ground to build the Economic and Monetary Union and realise Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa’s vision. Shortly after, the "One Market, One Money" study commissioned by the European Commission evaluated the benefits and costs of forming an economic and monetary union (European Commission 1990). These economic arguments were soon reinforced by political imperatives: the reunified Germany had to be firmly anchored in the EU (Buti et al. 2010).

The EMU institutional setting was based on a ‘strong’ version of the policymaking consensus that prevailed in the 1980s (Buti and Sapir 1998) and considered macroeconomic stability as the overarching goal. A centralised and independent monetary policy would credibly bring down inflation (Barro and Gordon 1983, Rogoff 1985) and keep output close to potential. In order to avoid ‘fiscal dominance’ and possible government bailout (Sargent and Wallace 1981), excessive government deficits and monetary financing of government deficit would have to be banned. Moreover, in line with the tax smoothing theory (Barro 1979), tax rates would be held constant over the business cycle. Hence, fiscal policy was to be limited to automatic stabilisation during normal cycles. Financial markets were expected to allocate resources efficiently within and across Member States. Finally, the EU competencies in competition and trade policies, as well as the progress in the internal market (European Commission 1988) would suffice to increase market efficiency gains, notably through increased competition. These were expected to spread across the economies while trade integration was set to make the euro area eventually satisfy the optimum currency area (OCA) criteria endogenously (Frankel and Rose 1998).

These principles were enshrined the Maastricht Treaty, which notably set the convergence criteria required for Member States to join the common currency. These criteria focus on price stability, government budget deficits, government debt-to-GDP ratios, exchange rate stability and long-term interest rates. While the convergence criteria ensured euro area Member States would nominally converge prior to adopting the euro, the Stability and Growth Pact, adopted in 1997, aims at maintaining and enforcing fiscal discipline in the EMU over time. The independence of the European system of central banks (the ECB and the national central banks of Member States) and its focus on the primary objective of price stability aimed to achieve macroeconomic stability. Finally, competition policy, with its unicum of state aid policy, was meant to ensure efficiency and, together with macroeconomic stability, economic convergence.

The euro area throughout the crisis: Weaknesses of EMU’s architecture come to the fore

During its first ten years, the euro area grew on average at par with the US in terms of GDP per capita and the ECB quickly gained credibility and was able to bring inflation in line with its target of “below but close to 2%”. At the same time, structural reforms stalled and the benefits of lower interest rates and easier access to credit – both in the public and private sector – gave rise to an ‘anaesthetic effect’, slowing down reform efforts and fiscal consolidation in peripheral countries (for more details, see Buti 2018). The financial crisis which started in the summer 2007 stands as the first major test case for the euro area. The crisis, at least in Europe, was triggered by a conjunction of factors and unfolded through many channels: current-account imbalances, sometimes related to productivity developments, banking sector shocks and their relation with sovereign debt. It was thus a strong catalyst to test the solidity of the Maastricht institutions and revisit the validity of the underlying assumptions. The financial crisis brought to the surface the weaknesses of the initial EMU architecture and the policy divergences of the first ten years of the euro.

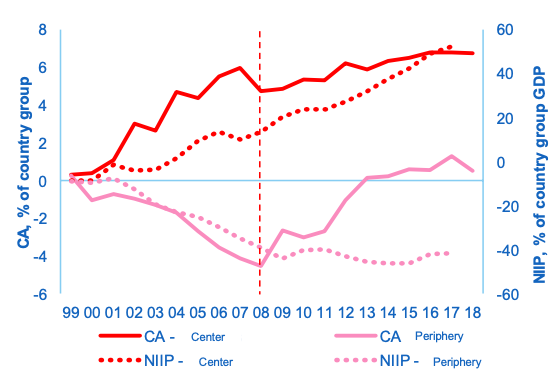

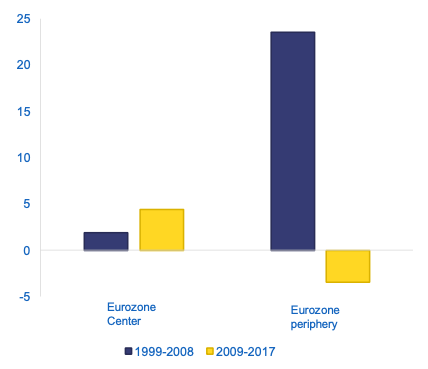

First, in the absence of exchange-rate risks, investors did not take into account country-specific risks both in the banking and in the government sector. Second, economies in the periphery (like Ireland, Portugal, Spain, or Greece) were expected to rapidly converge with core euro area countries thanks to capital and credit inflows (Baldwin and Giavazzi 2015), as counterparts of sustained current account deficits. However, part of those inflows went into government sovereigns and in non-tradeable sectors (Figure 1), driving prices up, eventually resulting in an appreciation of their real exchange rates (Buti and Turrini 2015). While at the euro area level, the current account was broadly in balance, divergences between creditors and debtors aggravated. In relative terms, the periphery became more intensive in non-tradeable while core countries gained competitiveness. The resulting changes in industrial structure resulted in agglomeration effects and, over time, contributed to diverging social and political preferences.

During the crisis, the negative effects of capital misallocation and excessive debt levels built over the preceding years came to the fore with the sudden stops of capital flows towards the periphery. These countries corrected their external accounts, but the adjustment was asymmetric as surplus countries did not boost domestic demand. As a result, the current account rebalancing proved considerably more painful in terms of output losses. The collapse in flows among banks gave rise to a sovereign problem, while, in the opposite direction, tensions on the sovereign weighed on banks’ balance sheets. The sovereign-bank ‘doom loop’ amplified financial distress and was responsible for deepening the recession, notably through worsened lending conditions in the economy.

Figure 1 Imbalances and resource allocation

a) Increasing imbalances

b) Cumulative growth rate of non-tradeable/tradeable value added

Notes: Centre includes Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. The periphery includes Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, France, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Centre and periphery euro area countries grouped according to their external position. Updated from Buti and Turrini (2012).

Source: Commission calculations based on AMECO

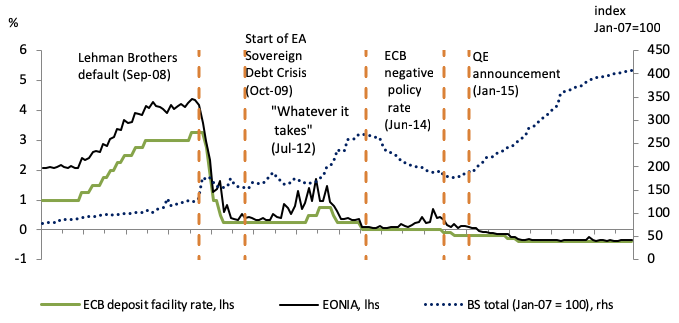

Upon sudden stops, the only institution that had the mandate and the means to intervene – namely, the ECB – did take action and inter-banking short-term flows were replaced by central bank lending (Figure 2). This provided the space for EMU governments to create the institutions necessary to deal with Members faced with extreme difficulties. However, the absence of a lender of last resort in the EMU construction made it impossible to prevent the geographically contained sovereign crisis to morph into a general crisis of the euro area. It was only in July 2012, when monetary policy transmission was completely impaired by the sovereign crisis, that, in order to restore market confidence, ECB President Mario Draghi announced: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

Figure 2 ECB policy and euro overnight rates, Eurosystem Balance Sheet size

Source: Macrobond, ECB

The pre-conditions for such a statement were laid out in the European Council conclusions of June 2012, in which leaders committed “to do what is necessary to ensure the financial stability of the euro area” and agreed to set up the Banking Union with the ultimate objective of tackling the negative loop between sovereign and bank risks.

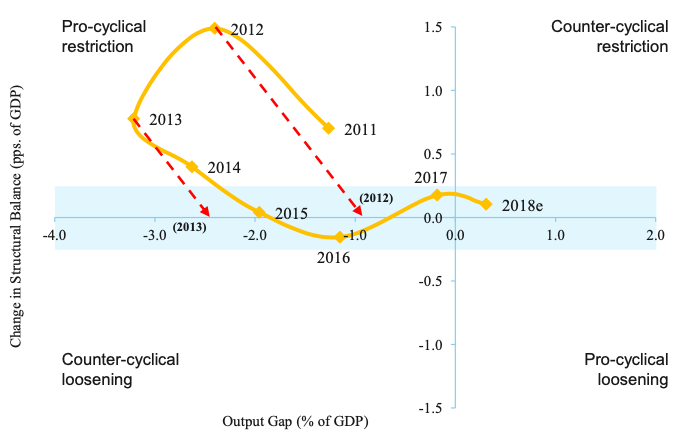

Whilst the financial crisis was not fiscal in origin (apart from Greece), the lost opportunity of reducing public debt in the first ten years of EMU and the lack of central fiscal stabilisation contributed to aggravate the slump. After the initial coordinated fiscal expansion in 2008, the lack of fiscal buffers at national level meant that, in many countries, fiscal policy was no longer available to respond effectively to the demand shortfall. As a result, the aggregate euro area fiscal adjustment became pro-cyclical from 2011 to 2014 (Figure 3). In such a context, a common stabilisation fiscal instrument for the currency union could have played an important role. Indeed, the presence of a euro area fiscal capacity allowing to fully compensate for the contractionary policy made by Member States in 2012 and 2013 (represented by the red dashed lines in Figure 3) would have sensibly reduced the output gap during the crisis leading to almost reach the output gap levels of 2016 three years in advance.

Figure 3 Fiscal stance over the economic cycle, euro area, 2011-2018

Source: Commission calculations based on Autumn 2018 Commission forecast

Note: This is computed with a multiplier equal to 1, with monetary policy at zero lower bound, large underutilized capacity and high private debt.

Reforms during the crisis, but job still not completed

Because of shortcomings in the construction of the EMU, countries in the euro area entered the financial crisis with too high government debt and excessive bank leverage, and without the institutions or mechanisms to manage shocks. Since then, reforms have aimed at preventing the repetition of this crisis and have led to overhauling the toolbox of EMU (European Commission 2017a). Efforts have notably been made to detect and correct macroeconomic imbalances, to better coordinate economic and fiscal policies and to provide financial assistance to Member States in financial difficulties through the European Stability Mechanism.

One of the salient actions was to initiate a Banking Union in 2012. The Single Supervisory Mechanism became responsible for supervision of banks throughout the euro area.

The Single Resolution Mechanism was set to sever the links between bank and sovereign stress by unifying the bank resolution and restructuring frameworks across countries and providing a common, industry-funded backstop. These two pillars of the Banking Union rest on the foundation of the single rulebook, which applies to all EU countries. The completion of the Banking Union requires a credible backstop and a common deposit guarantee (European Commission 2017c).

Progress towards private risk-sharing requires the completion of the Banking Union, overcoming the remaining fragmentation, and the advancement in the Capital Markets Union. The latter will allow the excess savings in some euro area members to be recycled via equity rather than via debt, which will considerably reduce the risks we witnessed in the pre-crisis period. In the medium term, a genuine euro area safe asset will also need to be considered (Buti et al. 2017).

On the fiscal side, more reforms to improve the stabilisation capacity of the euro area economies are needed (Buti and Carnot 2018). A central investment scheme could provide enough liquidity to compensate the effort made by the euro area members. To help monetary policy, some insurance mechanism would be necessary to manage the impact of large shocks and ensure that euro area Member States are not constrained to carry out pro-cyclical fiscal policies in a downturn. (European Commission 2017a). The first concrete proposal for a euro area fiscal capacity in the context of a multi-annual financial framework (2021-2027) came in May 2017 (European Commission 2017b).

Conclusion

Europe’s currency union is still in its teenage years. The foundations of the EMU were laid down in the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 and, in 2019, the euro celebrates its 20th year of existence.

While important reforms were undertaken during the European sovereign-debt crisis, this does not mean that the job is completed. The deepening of the euro area is an unfinished business. Two Euro summits took place in 2018 (in June and then in December). Leaders have endorsed the terms of reference for the common backstop to the Single Resolution Fund and the term sheet on the reform of the European Stability Mechanism. They have agreed on next steps to pursue the work on a European deposit insurance scheme. They also mandated the Eurogroup to work on the design, modalities of implementation, and timing of a budgetary instrument for convergence and competitiveness for the euro area going forward. While such reforms are important steps, a unified approach on EMU’s ‘final equilibrium’ is still missing.

To bridge competing visions on the way forward, mutual trust has to be rebuilt. In order to move to a genuine EMU, we need to restore the veil of ignorance (Rawls 1999) under the consideration that the creditors (and debtors) of today are not necessarily the creditors (and debtors) of tomorrow. This will require policy authorities to develop a vision of the common interest and a low discount rate in the decision-making. The upcoming campaign for the European Parliament election is an opportunity for a mature debate on the euro’s next frontier.

Authors’ note: The authors are writing in their personal capacity and their opinions should not be attributed to the European Commission.

References

Baldwin R and F Giavazzi (2015), The Eurozone Crisis: A consensus view of the causes and a few possible solutions, A VoxEU.org eBook.

Barro, R (1979), “On the Determination of the Public Debt”, Political Economy 87: 940.947

Barro, R and D Gordon (1983), “A Positive Theory of Monetary Policy in a Natural Rate Model', Journal of Political Economy 91: 589-610.

Buti, M (2018), “the Euro@20”, presentation to the Bank of Italy, Rome, 10 December.

Buti, M and N Carnot (2018), "The Case for a Central Fiscal Capacity in EMU", VoxEU.org, 7 December.

Buti, M and A Turrini (2015), “Three waves of convergence. Can Eurozone countries start growing together again?”, VoxEU.org, 17 April.

Buti, M, S Deroose, V Gaspar and J Nogueira Martins (2010), The Euro: the First Decade, Commission of the European Communities, Cambridge University Press.

Buti, M, S Deroose, L Leandro, and G Giudice (2017), "Completing EMU", VoxEU.org, 13 July.

Buti, M and A Sapir (1998), Economic Policy in EMU: A Study, European Commission Services, Clarendon Press.

Delors, J (1989), Report on Economic and Monetary Union in the European Community", Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union.

Eurobarometer (2018), “Flash Eurobarometer 473” report, October.

European Commission (1988), "Europe 1992: The Overall Challenge", SEC (88)524 final Brussels, 13 April.

European Commission (1990), "One Market, One Money, An Evaluation of the Potential Benefits and Costs of Forming an Economic and Monetary Union", European Economy No 44, Directorate-General for Economic Financial Affairs

European Commission (2017a), “Reflection Paper on the Deepening of the Economic And Monetary Union,” COM(2017) 291, 31 May.

European Commission (2017b), “Further Steps Towards Completing Europe's Economic and Monetary Union: a Roadmap”, COM(2017) 821, 6 December.

European Commission (2017c), “Completing the Banking Union”, COM(2017) 592, 11 October.

Frankel, J and A Rose (1998), "The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria", Economic Journal 108(449): 1009-1025

Rawls, J (1999), The Law of Peoples, Harvard University Press.

Rogoff, K (1985), "The Optimal Degree of Commitment to an Intermediate Monetary Target", Quarterly Journal of Economics 100: 1169-1189

Sargent, T and N Wallace (1981), "Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic", Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 5: 1-17.