Since the EU published its most recent trade strategy five years ago, the world has changed dramatically and with it the objectives to which trade policy needs to respond. Perhaps the most important of these changes is the increasingly geoeconomic nature of globalisation. Trade is used more and more as a tool for power projection rather than the generation of prosperity. Big powers use trade and investment to generate networks of dependencies, rather than building institutions to underpin rules-based free trade (Farrell and Newman 2019).

While this is the central challenge for the foreseeable future, trade strategy has a multitude of other challenges and objectives to respond to, from climate change to the growing frequency of epidemics, from populist protectionism to big power competition. In a new CEPR book (Bluth 2021), I discuss the implications for trade policy in detail (Bluth 2021).

Read Europe’s Trade Strategy for the Age of Geoeconomic Globalisation by Christian Bluth here.

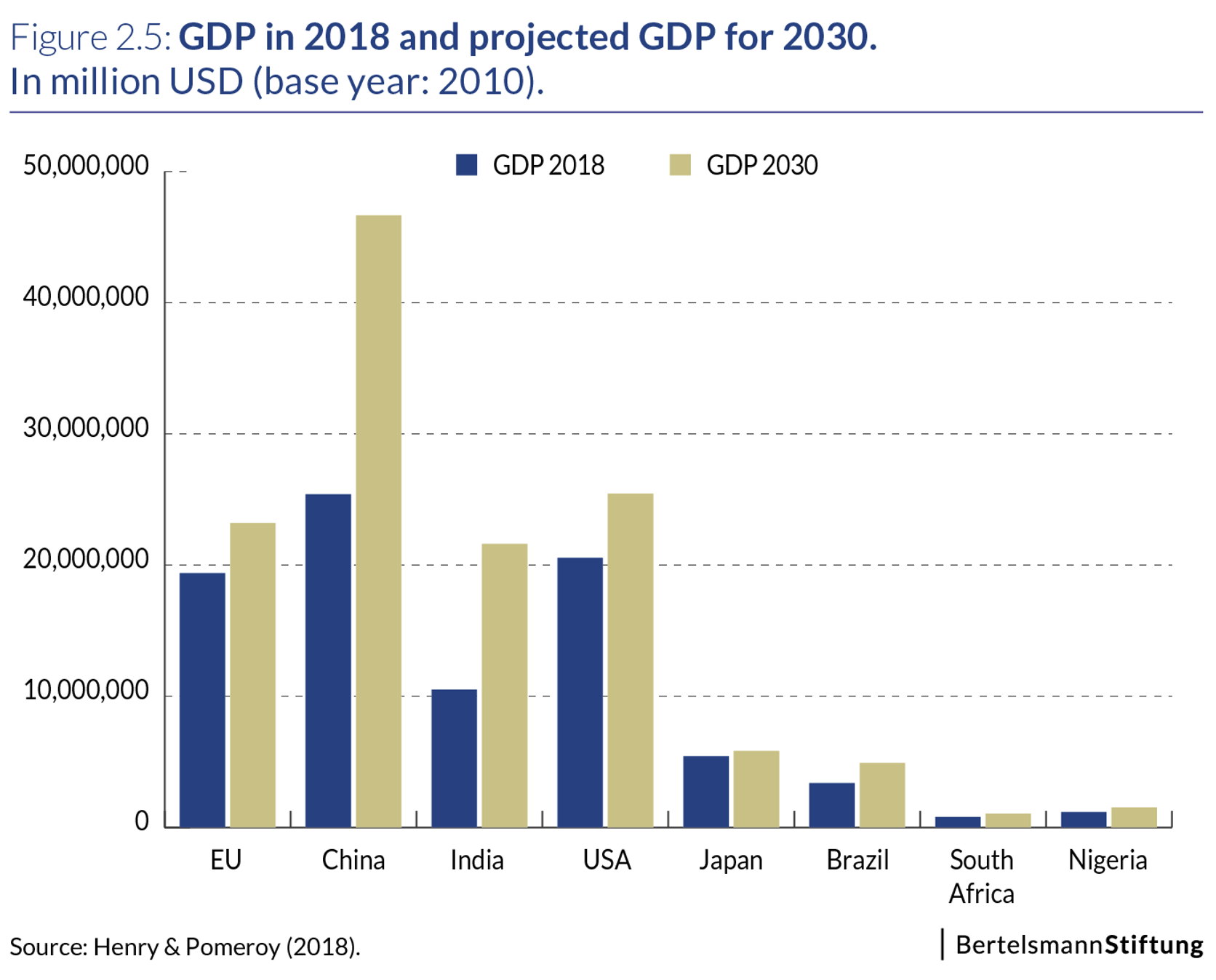

Figure 1 Estimated GDP for key economies in 2018 and 2030

Source: Henry and Pomeroy (2018)

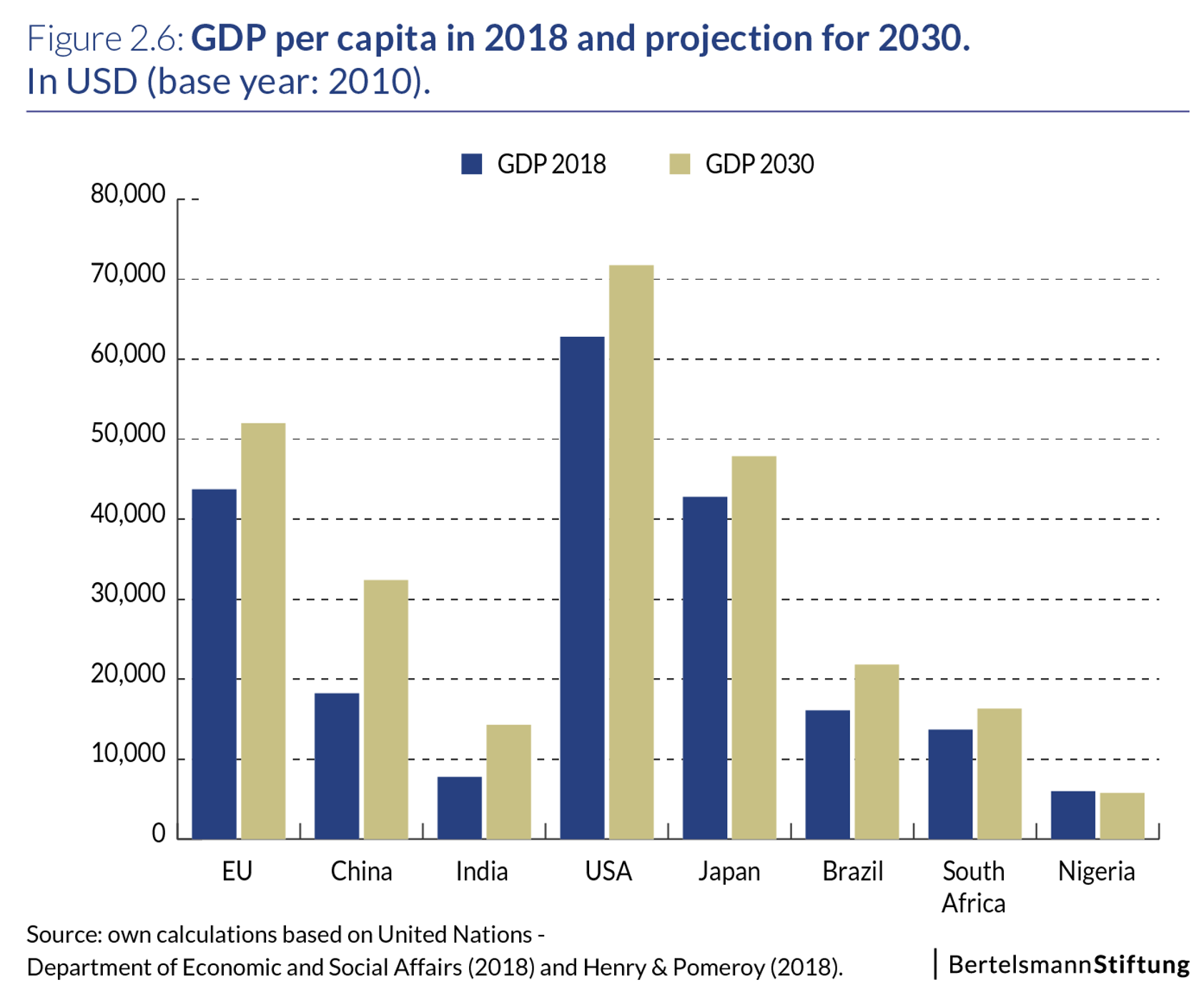

Figure 2 GDP per capita for key economies in 2018 and 2030

Source: Own calculations based on Henry and Pomeroy and United Nations (2018).

Non-political megatrends

The central non-political megatrends are the fundamental changes in the world's climate and demography, developments in technology, and the increased risk of future epidemics.

Climate change is a challenge for trade policy in several ways – especially since big trading nations are increasingly making use of aggressive carbon pricing in order to meet their emission targets. This risks changing profoundly the costs of production and, as a consequence, the localisation of production around the globe. In order to prevent leakage – i.e. production moving to low carbon price locations – the EU is contemplating introducing a carbon border adjustment tax (CBAT), which other trading powers may see as an illegitimate protectionist distortion of trade (Lowe 2019). I argue that a CBAT is a second-best solution and that the EU should make use of a political window of opportunity to create a plurilateral agreement with other large industrial nations on coordinating carbon pricing efforts which would also serve the environmental objectives of a CBAT without creating similar distortions. The EU should also seek free trade agreements (FTAs) with countries that have low-cost clean energy in order to bolster the global competitiveness of energy-intensive EU industries.

Climate change also threatens the world's food supply. While populations are rising, soil surfaces suitable for agricultural production are decreasing and extreme weather events make yields more volatile (United Nations Environment Programme 2019). Trade can play an important role in addressing local food shortages. This implies that the rules governing agricultural trade ought to be adjusted to meet the demands posed by rising global temperatures.

The size and wealth of populations are important determinants of a market's attractiveness. Global demographic dynamics therefore have important implications for trade policy. While the EU will remain a wealthy region, its relative share of the global population is declining. It is also unlikely to be a region of the world with the most dynamic growth patterns. This will translate into a gradual depreciation of the EU's bargaining power in trade policy, relative to other more populous and economically emerging world regions. Generally, the world will be ageing, which alters global investment and consumption patterns – a structural change which trade policy can accommodate. Africa's population is expected to rise dramatically, increasing the need to create economic opportunities for a young population.

Figure 3 EU falling behind US and China in cutting-edge patents

Source: Breitinger et al. (2020)

Technology is becoming an increasingly important factor determining competitiveness but also geoeconomic vulnerability or strength. Europe's capacity to innovate is lagging behind that of the US and China (Breitinger et al. 2019). It is vital that the EU increases its innovative capabilities if it is to remain globally competitive. It is also well known that the EU is underperforming when it comes to exploiting the opportunities of the digital revolution. It is important that the EU makes it easier for domestic digital business models to grow and scale up, improving its global competitiveness in this area. While defending important values, such as privacy and data protection, the EU should not succumb to digital protectionism, since the availability of digital solutions also matters for Europe's more traditional industries. In areas where digital solutions or platforms leave it geoeconomically vulnerable, the EU should consider developing its own capabilities or the diversifying the services deployed on its territory.

Finally, as the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, epidemics can have severe economic repercussions. As the frequency of epidemics is rising, this is increasingly a concern for trade policy. It is vital that critical medical supply chains continue to be operational and that – from a global perspective – production clusters in one location are avoided. Efforts to monitor supply and demand developments together with increased public stockholding can prevent further recourse to of export bans as in the spring of 2020.

Political megatrends

As important as these non-political megatrends are, the political megatrends constitute a more urgent threat to which EU trade policy needs to respond. This is particularly true for the accelerating big power competition between the US and China, but also for the tendency of ‘weaponising interdependencies’, the continued prevalence of protectionist populism and the weakening of multilateral institutions.

Both the EU and the US, along with many other countries, share several concerns about the trade implications of China's competition-distorting policies. Both find it difficult to obtain a serious policy reaction from China – the US trade war has not yielded much by way of substantial results, the EU's negotiations with China are slow to make progress. It is time for both trade policy powers to join forces and construct a multilateral initiative to address the distortions of the level playing field – in China, but also within other trading nations. The EU and the US should also use their influence to shore up the multilateral trading system and increase regulatory cooperation in order to maximise their normative influence.

A core feature of ‘geoeconomic globalisation’ is the ‘weaponisation of dependencies’, whereby trade powers seek to create asymmetric interdependencies that give them political leverage over a trading partner. The EU should therefore be careful about the dependencies it is entering into with other trading powers. The response should, however, not be reshoring of production and the pursuit of autonomy. Rather, the EU should monitor closely its supply network, diversify production chains, and try to avoid dependency on a single actor (company, country, or region). In addition, the EU should create strong defence instruments that can be deployed if a trading partner is weaponising the EU's dependency on it. Such instruments should be defensive in nature, aimed at acting as a deterrent, and the EU should make it clear that it does not intend to use such instruments aggressively, as Europe benefits from global trade integration and an over-assertive strategy may cause trading partners to reduce their dependencies on the EU in turn. If the deterrent is to become credible, the EU should also seek more streamlined decision-making mechanisms in foreign and security policy.

Rising populism is a serious challenge for EU trade policy. Political developments in trading partners, and potentially in the EU and its member states, might make trade policy less reliable and more difficult owing to increased politicisation. I argue that dealing with protectionist tendencies is best done with domestic policy tools, notably by improving the welfare state and its efficiency – providing insurance against trade-induced shocks. At the same time, it is important to maintain a societal consensus to embrace open trade, which also requires that rules and values are incorporated in trade agreements and enforced.

For the EU as a strong trading power, the weakening of multilateral institutions, in particular the WTO, is another growing challenge. There is a risk that multilateral policymaking falls victim to big power competition and geoeconomic globalisation. For the EU, it is vital to defend the liberal globalisation embodied in rules-based trade governance. The EU should therefore be careful to avoid any undermining of global economic trade governance, invest political capital in the system and play a constructive role, together with other nations supportive of liberal global trade, in modernising the WTO by making it more flexible and effective.1

References

Bluth, C J (2021), Europe’s Trade Strategy for the Age of Geoeconomic Globalisation, CEPR Press.

Farrell, H and A L Newman (2019), “Weaponised Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion”, International Security 44(1).

Henry, J and J Pomeroy (2018), The World in 2030: Our long-term projections for 75 countries, HSBC.

Lowe, S (2019), “Should the EU tax imported CO2?”, Centre for European Reform, 24 September.

United Nations (2018), Global Urbanization Prospects – The 2018 Revision, UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs.

United Nations Environment Programme (2019), Global Environment Outlook.

Breitinger, J C, B Dierks and T Rausch (2019), World class patents in cutting-edge technologies, Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Endnotes

1 A series of publications by Bernard Hoekman and others with concrete suggestions for WTO reform is available at https://ged-project.de/trade-and-investment/the-wto-as-a-cornerstone-of-the-post-covid19-relaunch-of-the-global-economy/