International cooperation between national supervisors broke down during the Global Financial Crisis. The collapse of Lehman and Fortis provide vivid illustrations that national supervisors ultimately choose for their national interest in crisis management. Reform of global governance, guided by the G20 and executed by the Financial Stability Board, has so far focused on soft law solutions (Arner and Taylor 2009). Regulators adopt a consensual approach towards the setting of international standards. For day-to-day supervision, home and host supervisors of global banks work together in supervisory colleges. For crisis management, home and host authorities cooperate in crisis-management groups. This approach is underpinned by legally non-binding Memoranda of Understandings, buttressed by peer reviews of each other’s supervisory system.

Game theory

In a new book on international banking (Schoenmaker 2013), I argue that such voluntary cooperation is bound to break down, in particular in crisis times when cooperation is most needed. The explanation is that financial stakes are high and national governments, which are accountable to their national parliament, only take care of the domestic effects of an international bank failure.

There is an emerging literature applying game theory to international cooperation for the provision of public goods (Barrett 2007). This can also be applied to analyse the public good of international financial stability. The international financial system is vulnerable to breakdown due to the financial trilemma, which comprise three parts:

- Global financial stability

- International banking

- National financial stability

If we want the first, then governments have to make a choice between the second and the third. There is no way out.

The national approach is costly

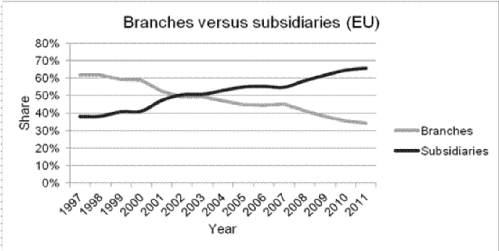

There is anecdotal evidence that host country supervisors informally push for ‘subsidiarisation’ to reassert their control over host operations. The subsidiary form is on the rise in the EU. Figure 1 illustrates that the share of foreign subsidiaries has increased from 38 to 66% over the last 15 years. In particular, the steep increase after the start of the crisis in 2007 is notable.

Figure 1 Relative share of branches and subsidiaries in Europe. The share is measured by cross-border assets in branches, respectively subsidiaries, as a percentage of overall cross-border assets in EU banks.

Source: EU Banking Structures, ECB.

Furthermore, the US is considering a sub-holding for US operations of foreign banks and the UK is consulting on a subsidiary requirement for US and Australian banks. These latter banks are subject to national depositor preference, leaving foreign depositors in the cold.

The costs of financial protectionism can be big, as national subsidiaries need to maintain separate liquidity pools and capital buffers. A first example is a pan-European bank. National supervisors force this bank to keep extra liquidity buffers up to €20 billion in the different countries in which it operates. With an opportunity cost of 1%, the annual cost amounts to €200 million. A second example involves a group of 25 European banks. Applying a shock in the form of a GDP drop of 2% and an interest-rate rise of 2%, Cerutti et al (2010) find that with ringfencing these banks need an additional €45 billion in capital. Without ringfencing, the banks need only €20 billion in extra capital.

A new international governance system

In Governance of International Banking (Schoenmaker 2013), I present governance solutions for the supervision and resolution of international banks. These solutions keep the integrated business model alive and obviate the need for separate liquidity pools and capital buffers at the national level.

The endgame of resolution sets the incentives for ex ante supervision. In that light, I apply a backward-solving approach, illustrated by the backward arrow for the fiscal backstop in Figure 2. The design of global governance thus starts with mobilising the funds for resolution, the so-called fiscal backstop. At the European level, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is fulfilling the role of the European crisis fund for countries and is now on the verge of expanding that role to banks.

A European governance system may therefore consist of the following building blocks: the European Commission as European rule maker, the ECB as European supervisor and lender of last resort, a new European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Authority, and the European Stability Mechanism as fiscal backstop (see Figure 2). The European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Authority will be the new player in this governance system. To minimise the cost for taxpayers and maximise private-sector involvement, this new authority should apply bail-in and build a fund, funded by risk-based premiums levied on the European banks. Only after that fund is exhausted would the European Deposit Insurance and Resolution Authority have access to the ESM.

Figure 2 European and global governance of financial supervision and stability. The framework illustrates the five stages from rule making to the fiscal backstop. The bottom shows the agency for each function at the European level and the world level, respectively.

Source: Schoenmaker (2013)

A bigger role for the IMF

Moving to the global level, the IMF is the international financial institution with resources for crisis management (Figure 2). The IMF would broaden its global support from sovereign countries to global banks and thus become the International Resolution Authority for global banks. The IMF already has the governance arrangements in place for involvement of, and accountability to, the ministers of finance who provide the resources to the IMF.

While many observers would also give the role of international supervisor of global banks to the IMF, I argue for the Bank for International Settlements for two reasons.

- First, supervisory independence, one of the core principles for effective banking supervision, would be violated;

As ministries of finance play a dominant role in the governance of the IMF, the IMF cannot act independently from government.

- Second, the functions of supervision and resolution should be separated;

Supervisors have a tendency towards forbearance hoping for better times, while resolution authorities aim for timely intervention to minimise the costs.

Conclusions

In the aftermath of the Global Crisis, national supervisors seem to go down the path of financial protectionism. To counter this, politicians need to come up with fresh solutions for international governance. These solutions boil down to burden sharing for the resolution of cross-border banks. In Europe, the first step is taken with a move towards banking union.

References

Arner, D and M Taylor (2009), “The Global Financial Crisis and the Financial Stability Board: Hardening the Soft Law of International Financial Regulation?’’, University of New South Wales Law Journal 32, 488-513.

Barrett, S (2007), Why Cooperate? The Incentive to Supply Global Public Goods, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Cerutti, E, A Ilyina, Y Makarova, and C Schmieder (2010), “Bankers Without Borders? Implications of Ring-Fencing for European Cross-Border Banks”, IMF Working Paper No WP/10/247.

Schoenmaker, D (2013), Governance of International Banking: The Financial Trilemma, New York, Oxford University Press.