Many companies have experienced a sudden and unanticipated decline in their revenues as a result of Covid-19, putting pressure on cash flows and leaving many with cash-flow deficits. Provided that revenues ultimately recover (even if not fully), the issue for most of these companies is not whether they remain solvent, but whether they have access to sufficient liquidity to finance temporary cash-flow deficits. Consistent with that, a key question for the economic outlook – one that has guided part of the public policy response – is whether illiquid, but solvent companies can access the finance they need to avoid a large number of unnecessary bankruptcies and the associated accumulation of economic scar tissue (Baldwin 2020).

This column summarises a large-scale accounting exercise that quantifies how the Covid-19 shock might affect the cash flows of individual UK companies and, by aggregating deficits up, the amount of liquidity that the UK corporate sector as a whole might need to weather the shock. This exercise is similar in spirit to the cross-country studies of Banerjee et al. (2020), De Vito and Gomez (2020), Bachas and Brockmeyer (2020), the US study of Crouzet and Gourio (2020) and the Italian study of Schivardi and Romano (2020). For more details on both the data and calculation, see Anayi et al. (2020) and Button et al. (2020).

The dataset

The dataset combines the latest available profit and loss accounts, cash flow statements and balance sheet data on public and private individual UK-incorporated private non-financial companies (henceforth referred to as ‘companies’) from listed company filings and Companies House. It captures variables like turnover, costs, profit, capital expenditure and a range of balance sheet items including cash and loans. The cleaned sample consists of around 95,000 companies, covering over £4 trillion in annual turnover. The sample has very good coverage of companies turning over more than £10 million, but poorer coverage of smaller SMEs and sole-traders (because these companies are not obliged to publish profit and loss accounts at Companies House). For that reason, we refer to companies in the sample as larger companies.

An illustrative Covid-19 scenario for the turnover of UK companies

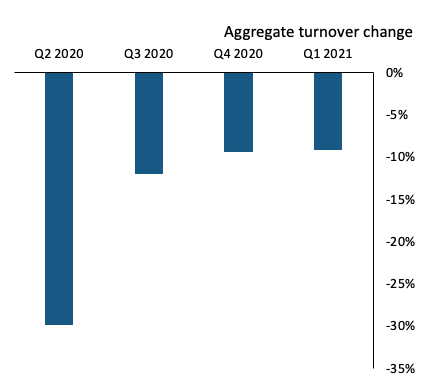

Figure 1 shows the assumed path for aggregate turnover for each quarter of the financial year 2020-21 with Covid-19 compared to a counterfactual without Covid-19. It is broadly consistent with the Monetary Policy Committee’s central projection described in the August 2020 Monetary Policy Report (Bank of England 2020). Underlying the central projection is an assumption that improved treatments or other health interventions become available, reducing the health and economic risks faced by households and businesses. As a result, the direct effects of the pandemic on the economy are assumed to fade gradually.

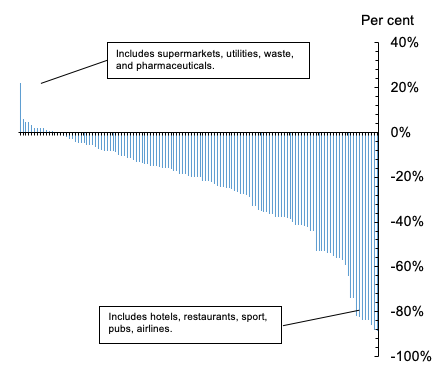

The Covid-19 shock is likely to have very different effects across sectors. Some sectors have been directly affected by social distancing. Others have been affected more indirectly by declines in non-essential spending, intermediate demand through the supply chain, or demand from abroad. Turnover has even increased in a minority of sectors as spending patterns have changed. Drawing on this logic, Figure 2 shows our sector-by-sector assumptions for turnover in 2020 Q2. These are broadly consistent with real-time spending indicators (summarised in the August 2020 Monetary Policy Report) and the UK Decision Maker Panel survey (Bloom et al. 2020). Beyond 2020 Q2, turnover in all sectors is assumed to recover gradually, consistent with the path in Figure 1, but with varying speeds depending on the sector.

Figure 1 Aggregate turnover change 2020 Q2 - 2021 Q1

Note: The chart shows the change in aggregate turnover in the illustrative scenario compared to a counterfactual in the absence of the Covid-19 shock.

Figure 2 Turnover change applied by sector and sub-sector in 2020 Q2

Note: The chart shows the modelled sector-by-sector change in turnover in the illustrative scenario in 2020 Q2 compared to turnover in the absence of the Covid-19 shock.

The mechanical accounting calculation

The cash-flow effect of these turnover shocks depends on how companies’ operating costs and other expenses change in response. We condition the calculations on an assumption that companies maintain their productive capacity at pre-Covid levels. This means that they are assumed to maintain employment and capital, including property and equipment. This assumption is intended to provide an indication of the amount of financing that could be required to mitigate the risk of scarring (Portes 2020).

In addition to maintaining productive capacity, companies are assumed to continue to pay rents, taxes and meet interest payments, but defer VAT and rental payments until the second half of the year. Other non-labour costs — the cost of goods and services used as inputs in production — trade credit and inventories are assumed to change in proportion to turnover. Finally, companies with negative cash flows are assumed to cut shareholder distributions to zero.

Cash flows are projected both with and without the fiscal measures that have been put in place to support UK companies and employment (as of August 2020). These include the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, cash grants and rates relief for smaller businesses, as well as Value Added Tax payment deferrals.

The cash-flow deficit estimates

Before accounting for fiscal policy, the aggregate cash-flow deficit of larger UK companies – the sum of deficits across all companies – is estimated to be around £160 billion in 2020-21. This is considerably larger than the ‘normal times’ cash-flow deficit of around £80 billion estimated from the pre-shock data (especially when considering the difference in assumptions about capital expenditure, which we assume to drop to maintenance level in our Covid-19 scenario).

The fiscal policy measures that have been put in place (as of August 2020) reduce the estimated cash-flow deficit considerably to around £135 billion.

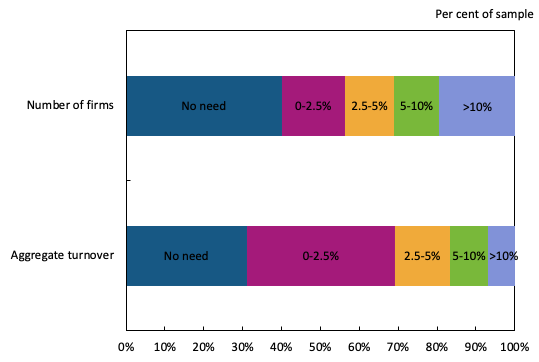

Figure 3 summarises the size distribution of the cash-flow deficits across companies in the sample. Around three in five companies are estimated to have a cash-flow deficit over the next year. This is more than double the proportion estimated in the pre-shock data. For many companies the deficit in this scenario is estimated to be small relative to turnover. Only around 20% of companies have an estimated deficit that is more than 10% of their pre-Covid turnover, and these companies account for a very small share of total turnover.

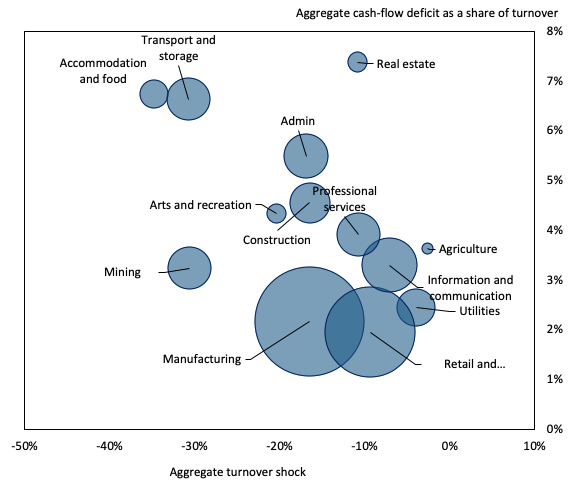

Figure 4 shows the individual company results aggregated to the sector level. Intuitively, sectors facing larger declines in turnover over the next year tend to have larger cash-flow deficits.

Figure 3 Estimate of the cumulative UK corporate cash-flow deficit after fiscal policy response from 2020 Q2-2021 Q1 as a share of turnover, distribution across companies in the sample

Source: ONS; S&P Capital IQ; Fame (Bureau van Dijk); Bank of England; Bank calculations.

Note: See the technical annex to the August 2020 Financial Stability Report for full detail on the methodology used.

Figure 4 Estimate of the cumulative UK corporate cash-flow deficit after fiscal policy response from 2020 Q2-2021 Q1, as a share of turnover for sectors on aggregate vs turnover shock applied

Source: S&P Capital IQ; Fame (Bureau van Dijk); Bank of England; Bank calculations.

Notes: The bubble sizes are in proportion to total turnover in the sector in the latest company accounts. Other services include public administration and defence, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities, and other services.

These estimates are highly uncertain. They depend heavily on the assumptions used, especially on the assumed path for turnover, both in aggregate and across sectors. While the company accounts data used is the most up-to-date one available, most of it is from the 2018-19 financial year. Financial positions will have evolved since then.

However, even despite this uncertainty, the aggregate cash-flow deficit estimate is likely to be an underestimate. That is because the dataset has very low coverage of companies with less than £10m in turnover which account for about 25% of the total turnover of UK-incorporated companies.

The assumption that companies maintain their pre-shock level of productive capacity is a useful benchmark. If companies are able to maintain productive capacity, then the economic downturn would be much less persistent. In reality, however, some companies will opt (or be forced) to cut their productive capacity. Indeed, some companies have already cut employment and several larger companies have announced that they intend to make redundancies in the near future. Under the assumptions that companies cut employment in proportion to the reduction in their turnover, adjusting for wage subsidies provided through fiscal policy, and the assumption that capital expenditure evolves in line with responses to the Bank’s Decision Maker Panel survey, the aggregate cash-flow deficit estimate is little changed. The reduction in labour costs is more-or-less offset by an increase in capital expenditure over the whole year, consistent with companies increasing investment above maintenance levels in the second half of the year as the economy recovers (Figure 1).

How might UK companies finance their cash-flow deficits?

The £135 billion aggregate cash-flow deficit estimate is sizeable. It is around three times larger than net lending to UK companies in 2019. There are various ways in which companies can finance deficits, all of which have been used throughout the shock to date.

Some companies will be able to use existing cash balances. As an extreme illustration, if companies were prepared to reduce their deficits by as much as possible using pre-Covid cash balances, then they could finance around £85 billion of the estimated cash flow deficit.

But many companies will be unable or unwilling to use cash and will seek external finance. Larger UK companies (under a similar, but slightly narrower definition than in our sample used to project cash flows) increased their borrowing by over £35 billion in the four months between March and June 2020. This includes over £15 billion in net bond issuance (mainly Investment Grade), around £5 billion in net commercial paper issuance (including those purchased by the government-backed Covid Commercial Financing Facility), and around £15 billion in net bank lending, supported by the UK government-sponsored loan schemes.

But debt is not the most appropriate form of finance for all companies. Public equity markets have remained open and a wide range of companies – including those in industries more directly affected by public health measures – raised capital totalling around £10 billion between March and June. There is also evidence that private equity markets are active and capable of providing further finance. Publicly available data suggests that funds invested in UK companies amount to £3 billion over the same period.

Taking into account the different sources of finance described above, net finance raised by larger companies exceeded £45 billion in the four months from March to June. While some of this is likely to have been used to finance anticipated cash-flow deficits, some may have been raised for precautionary reasons or to fund investment. Overall, while significant progress has been made, UK companies are likely to need to raise additional finance over the coming months to fill their cash-flow deficits.

Challenges ahead

Corporate insolvencies have remained at close to pre-Covid levels between March and June, but they are likely to rise. A minority of companies are likely to become insolvent even if turnover fully recovers because they were vulnerable already prior to the Covid-19 shock. For example, around £50 billion of the aggregate £135 billion cash-flow deficit estimate comes from companies that had a low credit rating, high leverage or were unprofitable pre-Covid. And the number of companies at risk of insolvency would increase if turnover does not fully recover in some sectors if Covid-19 precipitates or accelerates structural change (e.g. a shift from physical to online retail). Some debt restructuring is likely to be necessary (Becker et al. 2020).

Looking further ahead, there are likely to be two challenges. First, in order for productive resources to be rebuilt and reallocated as the economy recovers, it is necessary for new companies to enter the market and for incumbent companies to grow. To the extent that there are market failures in the provision of such finance, policy interventions to support the supply of finance would need to be different to the policies implemented throughout Covid-19 to date (see The Future of Growth Capital Report 2020). Second, some companies will naturally enter the recovery phase with more leveraged balance sheets, having accumulated debt to finance cash-flow deficits and survive the shock. Depending on the outlook for corporate earnings, interest rates, and credit supply, some of these companies may seek to delever, which could weigh on investment during the recovery.

Conclusions

The spread of Covid-19 and the measures taken to contain it have led to a sharp fall in economic activity, which we estimate could lead to a cash-flow deficit in the corporate sector of at least £140 billion over the next year. A large amount of finance has already been provided to UK companies, including via government-backed loan schemes. This has mitigated the immediate risk of large-scale corporate insolvency and the associated economic costs. Looking ahead, high and rising debt burdens could pose further challenges to corporate solvency, depending on the speed and nature of the recovery. And equity is likely to play a greater role, both as a means for some companies to repair their balance sheets and to finance entry of new companies as well as the growth of incumbents during the recovery.

References

Anayi, L, R Button, K Dent, J Hurley, M Rojicek, S Venables, M Waldron , D Walker and T Wise (2020), “Technical annex: updated estimates of the cash-flow deficit of UK companies in a Covid-19 scenario”, Bank of England, August 2020.

Bachas, P and A Brockmeyer (2020), “Using administrative tax data to understand the implications of COVID-19 (coronavirus) for formal firms”, World Bank Blogs.

Baldwin, R (2020), “Keeping the lights on: Economic medicine for a medical shock”, VoxEU.org, 13 March.

Banerjee, R, A Illes, E Kharroubi, J-M Serena (2020), “Covid-19 and corporate sector liquidity”, BIS Bulletin No. 10, 28 April.

Bank of England (2020), August 2020 Monetary Policy Report.

Becker, B, U Hege, P Mella-Barral (2020), “Corporate debt burdens threaten economic recovery after COVID-19: planning for debt restructuring should start now”, VoxEU.org, 21 March.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, S Chen, P Mizen and P Smietanka (2020), “The economic impact of coronavirus on UK businesses: early evidence from the Decision Maker Panel”, VoxEU.org, 27 March.

Button, R, D Gray, J Hurley, L Kirkham, M Melolinna, M Rojicek, M Waldron and D Walker (2020), “Technical annex: the cash-flow deficit of UK companies in a Covid-19 scenario”, Bank of England, May 2020.

Crouzet, N and F Gourio (2020), “Financial positions of U.S. Public Corporations”, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Chicago Fed Insights.

Deloitte, Innovate Finance and Scaleup Institute (2020), The Future of Growth Capital.

De Vito, A and J-P Gomez (2020), “Preventing a corporate cash crunch among listed firms“, VoxEU.org, 20 March.

Portes, J (2020), “The lasting scars of the Covid-19 crisis: channels and impacts”, VoxEU.org, 1 June.

Schivardi, F and G Romano (2020), “Liquidity crisis: keeping firms afloat during Covid-19”, VoxEU.org, 18 July.