The output decline in the current crisis could be larger than any since the Great Depression. Successful policy responses by governments should address both the financial crisis and the fall in aggregate demand, however in this crisis the macro policy options are limited. While each single country can adopt an export-led recovery strategy, this is clearly not an option open to the world as a whole. Likewise, the financial nature of the crisis weakens the traditional monetary transmission mechanism and the room to further lower central bank policy rates is limited.

Given these limits, this column focuses on fiscal stimulus, basing the analysis on the work in our recent IMF Staff Position Note, (Spilimbergo et al 2008).

Features of optimal fiscal stimulus packages

A fiscal stimulus should be:

- timely (as there is an urgent need for action),

- large (because the drop in demand is large),

- lasting (as the recession will likely last for some time),

- diversified (as there is uncertainty regarding which measures will be most effective),

- contingent (to indicate that further action will be taken, if needed),

- collective (all countries that have the fiscal space should use it given the severity and global nature of the downturn), and

- sustainable (to avoid debt explosion in the long run and adverse effects in the short run).

The challenge is to provide the right balance between these sometimes competing goals -- particularly, large and lasting actions versus fiscal sustainability.

Fiscal Policy in Financial Crises -- Lessons From History

A survey of the countries that have experienced severe systemic financial crises shows that these episodes are typically associated with severe economic downturns and that countries have reacted to these downturns quite differently, depending on economic and political constraints (See Chapter 4, World Economic Outlook, October 2008). The list of countries that have experienced both financial and economic crises includes some well known cases:

- Korea in 1997,

- Japan in the 1990s,

- the Nordic countries in the early 1990s,

- the Great Depression in the 1930s, and

- the US during the Savings and Loans crisis in the 1980s.

Several lessons can be drawn from these case studies.

- First, successful resolution of the financial crisis is a precondition for achieving sustained growth; delaying action led to a worsening of macroeconomic conditions, resulting in higher fiscal costs later on.

Prompt and sizeable support to the financial sector by the Korean authorities limited the duration of the macroeconomic consequences thus limiting the need for other fiscal action.

- Second, the solution to the financial crisis always precedes the solution to the macroeconomic crisis.

- Third, a fiscal stimulus is highly useful (almost necessary) when the financial crisis spills over to the corporate and household sectors with a resulting worsening of the balance sheets.

- Fourth, the fiscal response can have a larger effect on aggregate demand if its composition takes into account the specific features of the crisis.

In this regard, some of the tax and transfer policies implemented early in the Nordic crises did little to stimulate output. Fixing the financial system and supporting aggregate demand are, thus, both critical. This note focuses only on the fiscal component.

Composition of a fiscal stimulus in a long, unusual recession

Two features of the current crisis are particularly relevant in defining the appropriate composition of the fiscal stimulus.

First, as the current crisis will last at least for several more quarters, the argument that implementation lags for spending are long is less relevant when facing the current risk of a more prolonged downturn. Furthermore, given the highly uncertain response of households and firms to an increase in their income through taxes and transfers, expenditure measures may have an advantage by directly raising aggregate demand.

Second, since the current crises is characterized by a number of events and conditions not experienced in recent decades, existing estimates of fiscal multipliers are less reliable in informing policymakers about which measures will be relatively effective in supporting demand. This provides a strong argument for policy diversification ─ not relying on a single tool to support demand. (See Appendix I of Spilimbergo et al (2008) on the pros and cons of some specific spending and revenue measures.)

Public spending on goods and services

In theory, public spending on goods and services has a direct demand effect than those related to transfers or tax cuts. In practice, the appropriate increase in public spending is constrained by the need to avoid waste. What are the key prescriptions?

First, governments should make sure that existing programs are not cut for lack of resources. Governments facing balanced budget rules may be forced to suspend various spending programs (or to raise revenue). Measures should be taken to counteract the procyclicality built into these rules. For sub-national entities, this can be mitigated through transfers from the central government.

Second, spending programs, from repair and maintenance, to investment projects delayed, interrupted or rejected for lack of funding or macroeconomic considerations, can be (re)started quickly. A few high profile programs, with good long-run justification and strong externalities, can also help, directly and through expectations. Given the higher degree of risk facing firms at the current juncture, the state could also take a larger share in private-public partnerships for valuable projects that would otherwise be suspended for lack of private capital.

Public sector wage increases should be avoided as they are not well targeted, difficult to reverse, and similar to transfers in their effectiveness. But a temporary increase in public sector employment associated with some of new programs and policies may be needed.

Fiscal stimulus aimed at consumers

The support of consumer spending also needs to take the present exceptional conditions into account, specifically: i) decreases in wealth; ii) tighter credit constraints; and iii) high uncertainty. These three factors have different implications for the marginal propensity to consume out of transitory tax cuts or transfers. The first and the third suggest low marginal propensities to consume, the second a high one. Assessing the relative importance of the three is hard, but suggests two broad recommendations:

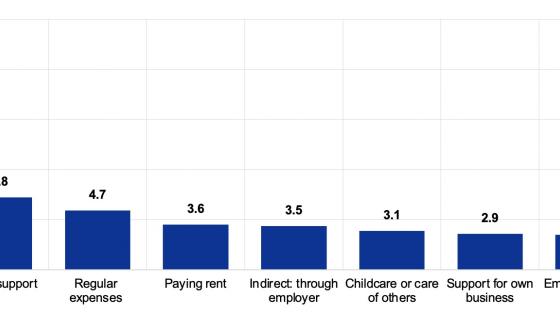

The first is to target tax cuts or transfers towards those consumers who are most likely to be credit or liquidity constrained. Measures along these lines include the greater provision of unemployment benefits, increases in earned income tax credits, and the expansion of safety nets in countries where they are limited. Where relevant, support for homeowners facing foreclosures using public resources supports aggregate demand and improves conditions in the financial sector. The second is that clarity of policy together with a strong commitment by policy makers to take whatever action may be needed to avoid the tail risk of a depression, are likely to reduce uncertainty, and lead consumers to decrease precautionary saving.

Some countries are considering broad based tax cuts. But, the marginal propensity to consume out of such tax cuts may be quite low. Some countries have introduced temporary decreases in the VAT. If the termination date is credible, the intertemporal incentives implied by such a measure are attractive. However, the degree of pass-through to consumers is uncertain, its unwinding can contribute to a further downturn, and it is questionable whether decreases of just a few percentage points are salient enough to lead consumers to shift the timing of their purchases. Possibly, larger, but more focused incentives, such as cash transfers for purchases of specific goods may attract more attention from consumers and have larger effects on demand.

Fiscal stimulus aimed at firms

In this uncertain environment, firms are also taking a wait-and-see attitude with respect to their investment decisions. Subsidies or measures to lower the tax-adjusted user cost of capital (such as reductions in capital gains and corporate tax rates) are unlikely to have much effect. Rather, the key challenge for policy-makers is ensure that firms do not reduce current operations for lack of financing. While this is primarily the job of monetary policy, there is also some scope for governments to support firms that could survive restructuring, but find it difficult to receive the necessary financing from dysfunctional credit markets. In particular, there is an argument for combining restructuring procedures with government guarantees on new credit.

It has been argued that governments should provide support to entire high-visibility sectors of the economy because of the potential effect that bankruptcies in these sectors may have on expectations. While there is some validity in this argument, its inherent arbitrariness, and risk of political capture, would make implementation difficult. Direct subsidies to domestic sectors could lead to an uneven playing field with respect to foreign corporations, and result in trade retaliation. An important principle of support should be to minimize interference with operational decisions. Credit guarantee to firms (not sectors) may be needed as long as the credit markets remain dysfunctional.

Sustainability concerns

It is essential for governments to indicate from the start that the extent of the fiscal expansion will be contingent on the state of the economy. Sizable upfront stimulus is needed, but policy makers must commit to doing more if needed. This should be announced at the start, so later increases do not look like acts of desperation.

At the same time, fiscal stimulus must not be seen as calling into question medium-term fiscal sustainability; questions about debt sustainability would undercut the near-term effectiveness of policy through adverse effects on financial markets, interest rates, and consumer spending.

Although some widening of borrowing costs within the euro zone may reflect sustainability concerns, financial markets do not seem overly concerned about medium-term sustainability. But markets often react late and abruptly. Thus, a fiscally unsustainable path can eventually lead to sharp adjustments in real interest rates, which in turn can destabilize financial markets and undercut recovery prospects.

Fiscal packages with the following features would help:

- implementing measures that are reversible or that have clear sunset clauses, or pre-committing to identified future corrective measures (e.g. future increases in upper income tax rates as part of the U.K. package);

- implementing policies that eliminate distortions (e.g., financial transaction taxes);

- increasing the scope of automatic stabilizers that, by their nature, are countercyclical and temporary;

- providing more robust medium-term fiscal frameworks should provide confidence that increases in public debt resulting are eventually offset;

- strengthening fiscal governance through independent fiscal councils that could help monitor fiscal developments, and also provide policy advice to reduce the public’s perception of possible political biases; and

- improving expenditure procedures to ensure that stepped-up public works spending is well directed to raise long-term growth (and tax-raising) potential.

It is also worth putting this into perspective. The main threat to the long-term viability of public finances in rapidly-aging countries comes from the net cost of publicly funded pension and health entitlements, whose net present values far exceed the magnitude of conceivable fiscal stimulus packages.

Finally, it should be noted that should spending will boost growth and thus tax revenues in the future. Many countries have succeeded in reducing their public debt burden through growth. A credible commitment to address these long-term issues can go a long way in reassuring markets about fiscal sustainability.

Some proposals for discussion

The gravity and singularity of the current crisis may require new solutions, which address specifically the issues of financial disintermediation and loss in confidence. Some proposals that could be considered are:

- Greater role of the public sector in financial intermediation

With the extreme shift in investors’ preferences towards liquid T-bills and away from private assets, the state is in a better position than private investors to buy and hold these private assets, and partly replace the private sector in financial intermediation.

Although the public sector does not have a comparative advantage in evaluating credit risk, nor in administering a diverse portfolio of assets, the management of the banking activities could be outsourced to a private entity.

- Provision of insurance by the public sector against large recessions

In the present environment of extreme uncertainty, the government could provide insurance against extreme recessions by offering contracts, with payment, contingent on GDP growth falling below some threshold level.

Banks could condition loan approvals on firms having purchased such insurance from the government. Widespread use of such contracts would provide an additional automatic stabilizer because payments would be made when they are most needed, namely in bad times. An obvious worry about such a scheme is that the government may not be able or willing to honor its obligations.

A collective international effort

The international dimension of the crisis calls for a collective approach. There are several spillovers that could limit the effectiveness of actions taken by individual countries, or create adverse externalities across borders.

Countries with a high degree of trade openness may be discouraged from fiscal stimulus since it will benefit less from a domestic demand expansion. The flip side of these spillovers is that if all countries act, the amount of stimulus needed by each country is reduced (and provides a political economy argument for a collective fiscal effort). At the same time, this collective fiscal effort must be tailored to country circumstances.

Some interventions currently discussed such as subsidies to troubled industries may be perceived as industrial policy by trading partners. The history of the Great Depression shows that, as the crisis deepens, there is increasing pressure to raise trade barriers. Such a race would bring significant costs in terms of efficiency.

All these factors point to the need for a concerted effort by the international community, and stricter coordination among countries with closer economic and institutional ties. Recent announcements by the EU recommending a 1.5% of GDP stimulus and the decision to finance some of the national expenditures from the EU budget are steps in this direction.

The most recent data are pointing more and more to a worldwide growth slowdown suggesting that the action should be widespread to maximize its effectiveness.

The IMF has called for a sizable fiscal response at the global level. Its precise magnitude should depend on several factors including the expected decline in private sector demand. Moreover, not all countries have sufficient fiscal space to implement expansionary fiscal policy since it may threaten the sustainability of fiscal finances. In particular, many low income and emerging market countries, but also some advanced countries, face additional constraints such as volatile capital flows, high public and foreign indebtedness, and large risk premia.

The fact that some countries cannot engage in fiscal stimulus makes it all the more important that others, including some large emerging economies, do their part. Also the policies should be tailored to those actions that are likely to provide the largest multipliers. In the United States, that is likely to be investment, other spending on goods and services, and some targeted transfers. In Europe, with its relatively large automatic stabilizers, the additional fiscal impulse can probably be somewhat less than in the United States.

Conclusion

The solution to the current financial and macroeconomic crisis requires bold initiatives aimed at rescuing the financial sector and increasing demand. The early resolution of financial sector problems is critical. But early, strong, and carefully thought out, fiscal responses are also important. Time and action are of the essence.

Editors' note: This column is a Lead Commentary on Vox's Global Crisis Debate where you can find further discussion, and where professional economists are welcome to contribute their own Commentaries on this and other crisis-linked topics.

References

Spilimbergo, Antonio, Steve Symansky, Olivier Blanchard, and Carlo Cottarelli (2008). “Fiscal Policy for the Crisis,” IMF Staff Position Note, December 29, 2008, SPN/08/