Over the last few decades, economic activity has been concentrated in the urban centres of a small handful of ‘superstar cities’ (Gyourko et al. 2013). The inelasticity of the housing stock in these urban centres has meant that a large fraction of the benefits from economic growth in the last few decades have accrued to property owners rather than improving the disposable income of local workers (Hornbeck and Moretti 2020, Hsieh and Moretti 2019).

We document how these urban agglomeration trends have shifted in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The social and economic disruption wrought by the pandemic led to large-scale migration (Coven et al. 2020), facilitated by increased work-from-home policies (Bartik et al. 2020, Bloom 2020), reduced commuting (Barrero et al. 2020), and shutdowns of city amenities. These changes raised the premium for housing characteristics found in suburbs and outlying areas, such as increased space and lower density (Bloom and Ramani 2021).

Empirical results

We study how the so-called bid-rent function has changed from before the pandemic to the present. The bid-rent function is the relationship between house prices or rents on the one hand, and distance from the city centre on the other hand. The bid-rent function for prices and rents is downward sloping. Prices and rents are highest in the city centre – reflecting land scarcity (and difficulty developing for regulatory reasons), urban amenities, proximity to work, and agglomeration effects – and fall the farther one moves away from the centre. We measure this gradient as the elasticity of prices and rents with respect to distance from the city centre and refer to it as the price gradient or rent gradient.

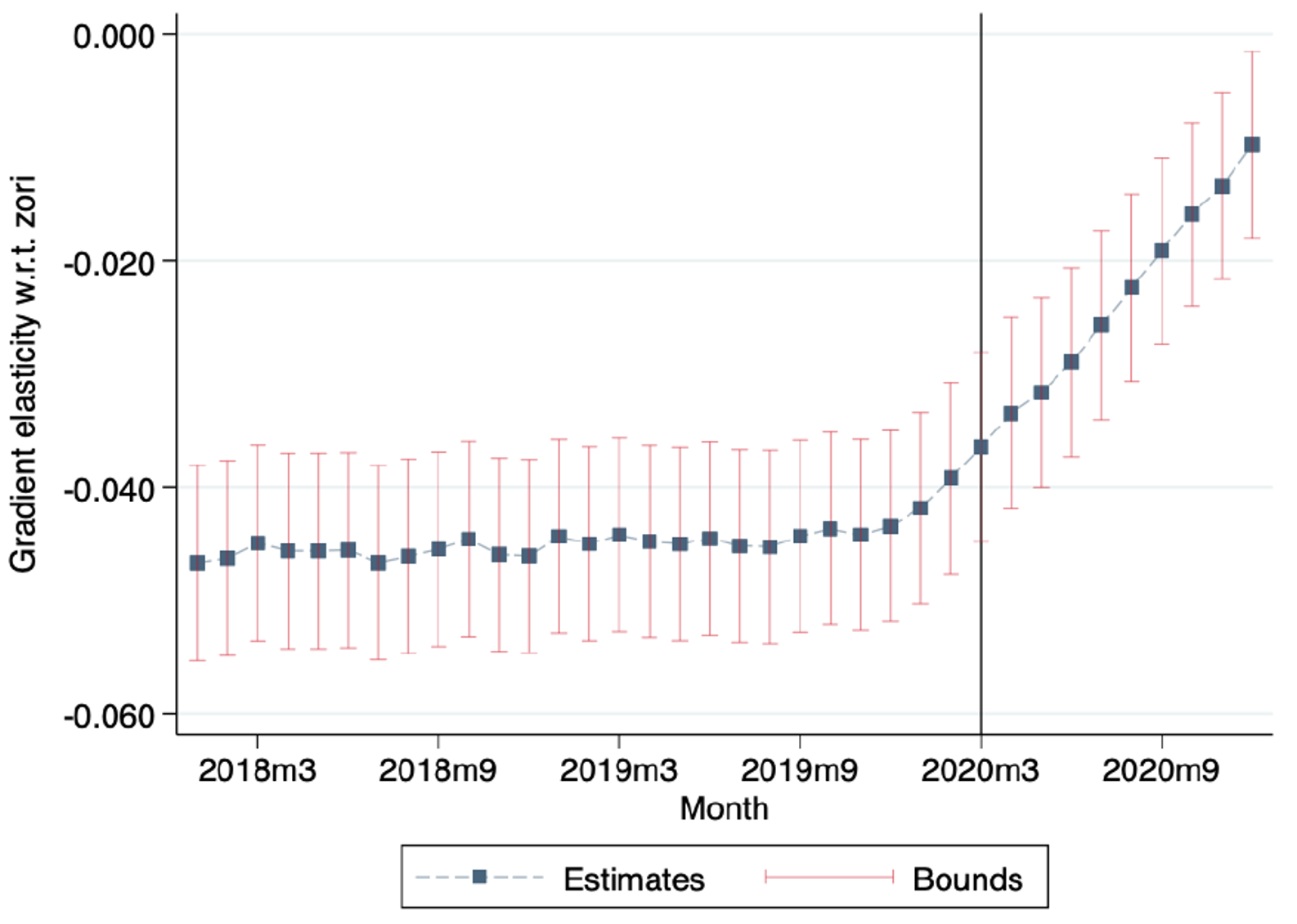

Using Zillow data at the zip code (postcode) level for the top 20 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the US, we first document changes in the rent gradient as a result of the pandemic. In Figure 1, we plot the estimated rent gradient month-by-month in a specification that includes MSA fixed effects. The rent gradient was -0.05 before the pandemic and stable over time. We find that this elasticity changed substantially after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The rent gradient flattened to -0.01 in December 2020. In economic terms, about 80% of the urban rent premium associated with urban living has reversed.

Figure 1

We also find a flattening of the price gradient, though it is smaller. We find that about 9% of the urban price premium has reversed.

The difference between our results in prices and rents suggests that a substantial component, but not all, of the Covid-19 shock is likely to be temporary. We investigate this issue through the lens of the present-value model of Campbell and Shiller (1988).

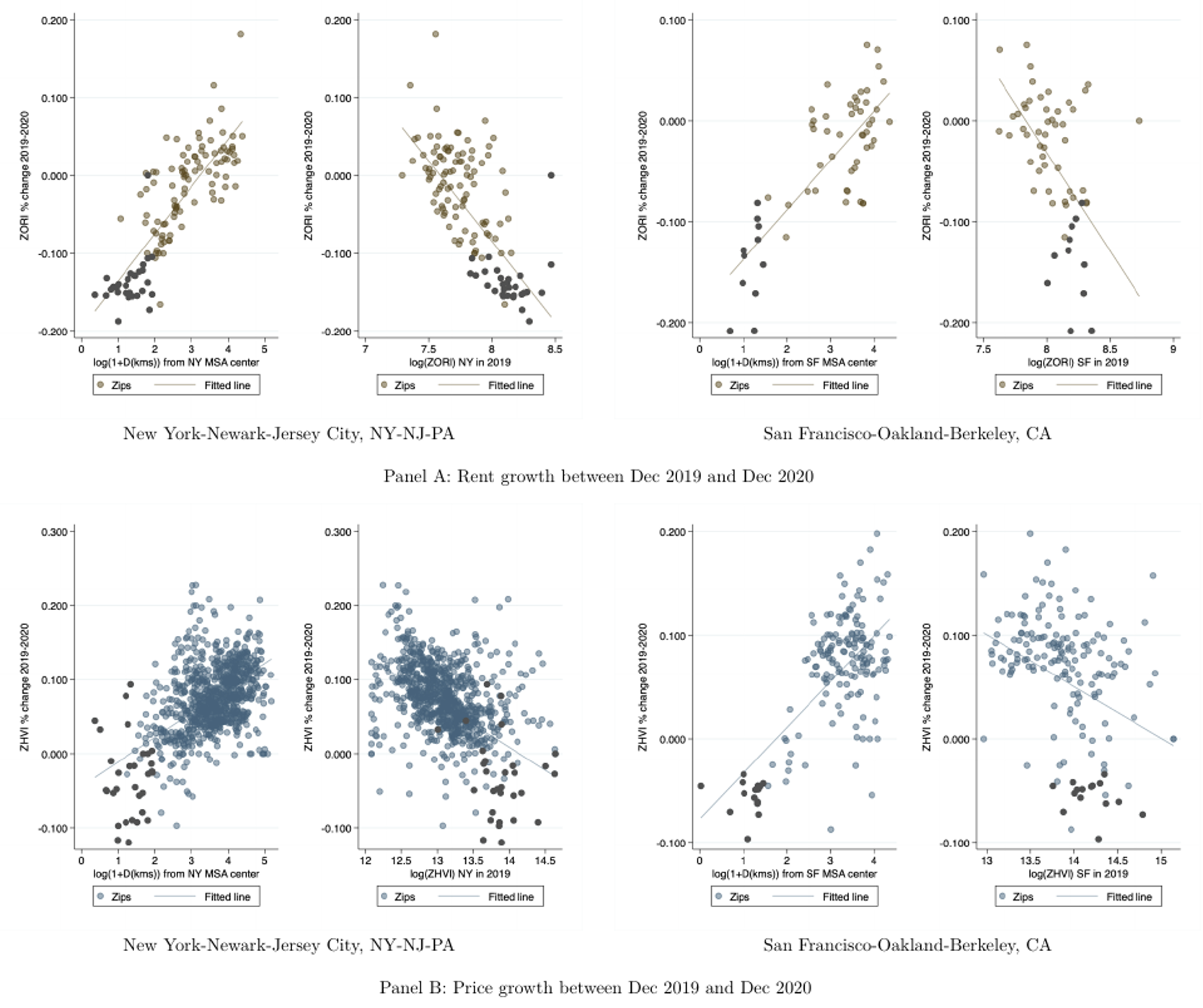

We find particularly strong effects when examining some of the largest and most expensive metropolitan areas in the US, such as New York City and San Francisco. The most expensive and centrally located areas had dramatic drops in both rents and prices, while cheaper suburban areas in the outlying districts saw increases in rents and prices. The stronger price effects in these cities points to more permanent shifts in work and residence patterns in the cities that were formerly the most desirable.

To illustrate, Figure 2 shows rent growth between December 2019 and December 2020 in Panel A, and price growth over the same period in Panel B. Growth is plotted as a function of distance from the city centre in the left plot, and as a function of pre-pandemic price or rent levels in the right plot.

Figure 2

We find similar patterns in list prices of properties for sale as in actual transaction prices. We also find that the number of active listings and days-on-the-market have shrunk in the suburbs and risen in the urban core.

Next, we use a simple present-value model in the spirit of Campbell and Shiller (1989) to infer what the changes in prices and rents imply for future rent growth expectations. If there are no changes in the urban-minus-suburban risk premia, and housing markets slowly return to their pre-pandemic state, then urban rent growth is expected to outpace suburban rent growth by 7.5 percentage points in the typical US metro over the next several years. This cumulative rent growth differential doubles to 15 percentage points if the urban-minus-suburban housing risk premium rises by 1 percentage point. If, instead of reverting to the old normal, the housing market changes that took place in 2020 are permanent, then the model implies that annual urban rent growth will exceed suburban rent growth by 0.5 percentage points absent risk premium changes, and by 1.5 percentage points if there is a 1 percentage point permanent change in relative risk premia. There is substantial variation in these numbers across metropolitan areas.

Finally, we try to better understand the variation across MSAs in the change in the price gradient. In our paper (Gupta et al. 2021), we regress the change in price gradient for each of the top-30 MSAs on several metro characteristics. We find strong evidence that cities with a greater fraction of jobs which can be done from home (Dingel and Neiman 2020) see a larger increase in their price gradient — suggesting that the greater adoption of remote work practices has led to a flattening of real estate prices.

We also find evidence that metros with more inelastic supply experience, as measured by either land unavailability (Lutz and Sand 2019) or the Wharton regulatory index (Gyourko et al. 2008), also experience reversals in their local price gradients. This suggests that some of the most inelastic regions are experiencing a reversal in urban concentration, and residents are migrating to suburban areas and other metros that have higher land elasticity. Prior research has indicated that as much as half of the national increase in rents over 2000-2018 has come from individuals sorting to inelastic areas (Howard and Liebersohn, 2020). If individuals continue migrating to areas which are both cheaper and more elastic in their housing supply, future housing cost increases will moderate compared to the recent past. Our results point to dynamic aggregate gains for renters if Covid-associated resorting continues.

Conclusion

A central paradox of the internet age has been that digital tools, which enable greater collaboration at further distances, have led to even more concentrated economic activity into a handful of dense urban areas. We document that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a partial reversal of this trend. The dispersal in activity is particularly strong for rents, but is apparent for prices as well, suggesting that some of the rent effects may last even after the end of the pandemic. These shifts in economic activity appear to be related to practices around working from home, suggesting that they may persist to the extent that employers continue to allow remote working practices. A key benefit to workers of this changing economic geography is access to the larger and more elastic housing stock at the periphery of cities, suggesting that rising rents may not weigh down the economic recovery as they did in past booms.

References

Barrero, J M, N Bloom and S Davis (2020), “60 million fewer commuting hours per day: How Americans use time saved by working from home”, VoxEU.org, 23 September.

Bartik, A, Z Cullen, E Glaeser, M Luca and C Stanton (2020), “How the COVID-19 crisis is reshaping remote working”, VoxEU.org, 19 July.

Bloom, N (2020), “How working from home works out”, SIEPR Policy Brief.

Bloom, N and A Ramani (2021), “The doughnut effect of COVID-19 on cities”, VoxEU.org, 28 January.

Coven, J, A Gupta and I Yao (2020), "Urban flight seeded the Covid-19 pandemic across the United States", SSRN 3711737, 20 October.

Dingel, J I and B Neiman (2020), "How many jobs can be done at home?", Journal of Public Economics 189: 104235.

Gyourko, J, C Mayer and T Sinai (2013), "Superstar Cities", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5(4): 167–99.

Gyourko, J, A Saiz and A Summers (2008), "A new measure of the local regulatory environment for housing markets: The Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index", Urban Studies 45.3: 693–729.

Gupta, A, V Mittal, J Peeters, and S Van Nieuwerburgh (2021), “Flattening the Curve: Pandemic-Induced Revaluation of Urban Real Estate”.

Hornbeck, R and E Moretti (2020) "Estimating Who Benefits From Productivity Growth: Local and Distant Effects of City TFP Shocks on Wages, Rents, and Inequality".

Howard, G and J Liebersohn (2020), “Why is the Rent So Darn High?”, SSRN 3236189, 31 July.

Hsieh, C-T and E Moretti (2019), "Housing constraints and spatial misallocation", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11.2: 1–39.

Lutz, C and B Sand (2019), "Highly disaggregated land unavailability", SSRN 3478900, 31 October.