How colonial extractive institutions affected social and economic development in the colonised countries is the subject of a large and growing body of research in economics and economic history (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, Dell 2010, Frankema 2010). While much of this research has focused on the long-run effects on economic outcomes in the present (Dell and Olken 2020), less is known about the immediate but long-running effects of colonial systems. We add to this research by investigating how the Dutch forced labour regime, known as the ‘Cultivation System’, affected the health of the population in 19th-century Java (de Zwart et al. 2022). We focus on mortality rates, as these are often considered a good indicator of wider demographic, health, and economic conditions (Sen 1998, Deaton 2013).

The Cultivation System was one of the most extractive forced labour regimes ever to exist. In this system, Javanese peasants were forced to devote a substantial share of their land and labour to the production of various cash crops, such as sugar, coffee, tea, tobacco and indigo. Despite the fact that these commodities were highly valued and therefore sold at very profitable rates in international markets, the local peasantry in Java received very little in return for their labour and land devoted to the cultivation of these crops. Moreover, this low cash payment (known as the ‘crop payment’) often returned into government coffers as it had to be used to pay the monetary land tax.

During most of the 19th century, the system was highly effective at increasing the output of cash crops from the island. For example, sugar production increased from 6,700 tonnes in 1831 to over 100,000 tonnes per annum in the late 1850s, while coffee production rose from 20,000 tonnes in 1829 to almost 55,000 in the late 1850s. Unsurprisingly, the system was also extraordinarily profitable for the Dutch government. At its height in the 1850s, net transfers from the East Indies – known as the ‘batig slot’ – were almost 4% of Dutch GDP and accounted for over 50% of total government revenue.

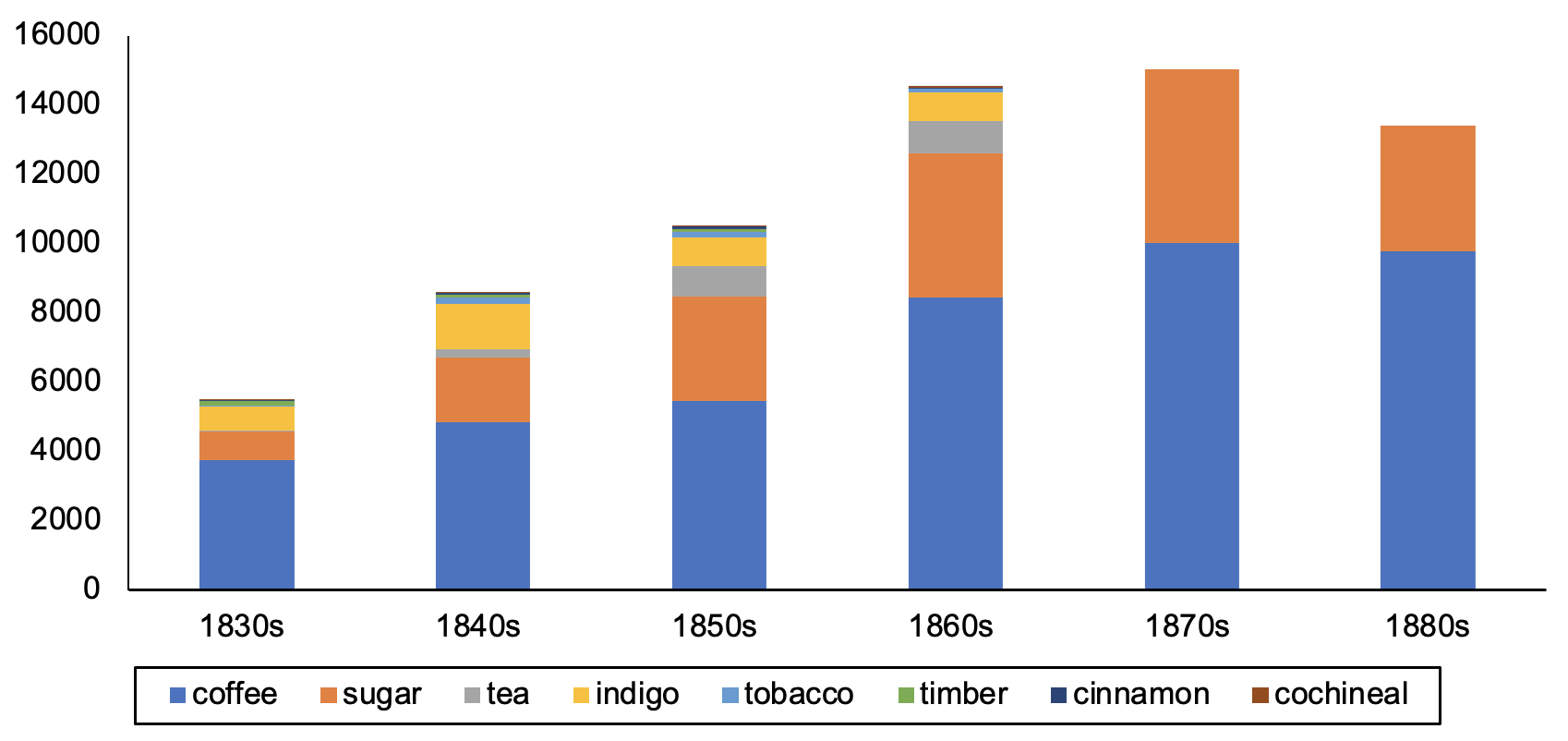

Figure 1 Value of crop payments to Javanese peasants for main cultivation crops

The system deeply intervened in local society as it involved over 70% of all Javanese households at its height. Both European and local elites were incentivised to push for higher production by the peasants via the so-called ‘kultuurprocenten’, or cultivation percentages, which represented a share of the total sale proceeds of these crops in the Netherlands.

Among the higher echelons of the colonial administration – both Dutch and Javanese – the income from these proceeds was excessive and their wealth became legendary. For lower Javanese heads, such as village chiefs, these proceeds were lower, but in terms of their relative importance in total income they may have even been more important as they received little income besides it. Via these kultuurprocenten, market prices exerted an influence on the demands placed on the local peasantry. The system was gradually abolished after 1870, when the Dutch East Indies were opened up for private enterprise and forced cultivation for the government slowly declined (see Figure 1).

There has been debate about the consequences of the system for the economic fortunes and wellbeing of the Javanese population since the nineteenth century. Contemporary commentators already suggested Javanese nineteenth-century destitution may be directly linked to the Cultivation System. Such views were confirmed in more recent historical research showing declining trends of per capita consumption and food availability (Booth 2016, van Zanden 2010).

Other researchers, however, emphasised that the Cultivation System may have led to increased commercial opportunities and the creation of a globally competitive sugar industry (Bosma 2013, Elson 1994). A recent analysis suggests that areas that were located near the sugar factories in the mid-nineteenth century have higher levels of industrialisation, education and household consumption than other areas today, mainly as a result of the persistent effects of increased investment in infrastructure (Dell and Olken 2020).

How was this system related to health conditions and mortality rates? Much of the labour in the Cultivation System had to be done on plantations, with workers who spent the night there while others travelled daily between their villages and the fields. The plantations themselves, described as unhygienic sites by contemporaries, formed particular hotbeds of disease, while the movement of workers contributed to illness spread throughout a region. Colonial investigations from the early 20th century confirm the link between plantations and infectious disease diffusion, although this information was not well received by everyone. The colonial medical official who wrote this down in his report was later discharged from service. Additional qualitative evidence suggests workers on government plantations were often malnourished, which weakened their immune systems and made them more susceptible to disease.

To see whether labour in the Cultivation System was indeed related to higher mortality rates, we compiled a dataset for 16 residencies (that is the largest administrative regional unit in the Dutch East Indies) for the years 1834 and 1879 – a period that covers the rise and decline of the Cultivation System. The dataset includes figures on the number of workers called for Cultivation System labour each year in the different residencies, as well as the overall size of population, mortality and birth rates, and finally, other indicators of local economic and social development that allow us to isolate the effect of forced labour on mortality.

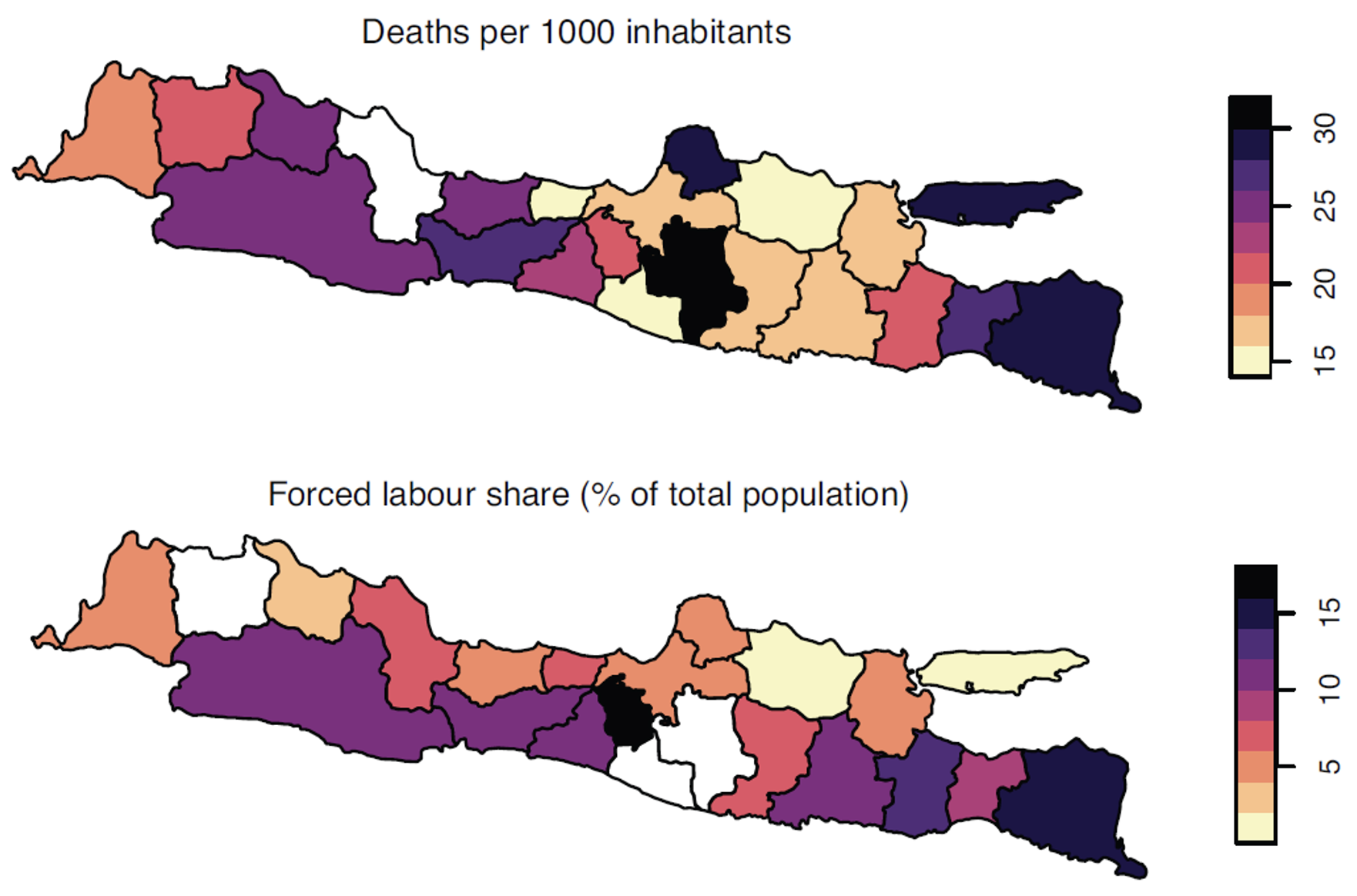

Some of the information we gathered is shown in Figure 2, where we can see that, roughly, places with high forced-labour demands were particularly deadly. Through our econometric analysis, we indeed find that, ceteris paribus, a higher number of workers called up for labour in the Cultivation System is related to a higher mortality rate. Our estimates suggests that in 1840, for example, for every additional 1,000 workers engaged in the Cultivation System, total deaths increased by 30. Over the long run, our calculations show that the abolishment of this system of exploitation by the late 19th century resulted in higher health levels. We estimate that the effect of this development was sizeable: as the number of forced labourers called up each year was about halved between the 1830s and 1870s, this caused mortality rates to decline by 10–30%.

To deal with endogeneity concerns, we employ an instrumental variable approach using variations in market prices for coffee and sugar in Amsterdam – that cannot have been influenced by mortality rates in the different residencies of Java – to predict the number of forced labourers in each residency. These analyses confirm the patterns described above suggesting that the link between forced labour in the Cultivation System and mortality was, in fact, causal.

Figure 2 Spatial distribution of mortality rates and forced labour share

This research has important implications. Whereas some earlier research highlighted potential beneficial impacts on commercialisation and long-run infrastructure investments, our study suggests that the effects on local health and wellbeing for Javanese in the nineteenth century were clearly negative. This suggests the importance of disentangling the effects on economic outcomes and on health, as well as between the immediate and long-run effects, as these may differ. When evaluating the effects of colonialism on local wellbeing, it is thus highly important to take into account more indicators rather than purely economic ones.

References

Acemoglu, D and J A Robinson (2012), Why nations fail: The origins of power, poverty and prosperity, Crown Business.

Booth, A (2016), Economic change in modern Indonesia: Colonial and post-colonial comparisons, Cambridge University Press.

Bosma, U (2013), The sugar plantation in India and Indonesia: Industrial production, 1770–2010, Cambridge University Press.

Deaton, A (2013), The great escape. health, wealth and the origins of inequality, Princeton University Press.

Dell, M (2010), “The persistent effects of Peru’s mining mita”, Econometrica 78(6): 1863–1903.

Dell, M and B A Olken (2020), “The development effects of the extractive colonial economy: The Dutch cultivation system in Java”, Review of Economic Studies 87 (1): 164–203.

de Zwart, P, D Gallardo- Albarrán, A Rijpma (2022), "The demographic effects of colonialism: Forced labor and mortality in Java, 1834-1879", Journal of Economic History 82 (1): 211-249 (see also CEPR Discussion Paper 17112).

Elson, R E (1994), Village Java under the cultivation system, 1830-1870, Allen & Unwin.

Frankema, E (2010), “The colonial roots of land inequality: Geography, factor endowments, or institutions?”, Economic History Review 63 (2): 418–51.

Sen, A (1998), “Mortality as an indicator of economic success and failure”, The Economic Journal 108 (446): 1–25.

van Zanden, J L (2010), “Colonial state formation and patterns of economic development in Java, 1800-1913”, Economic History of Developing Regions 25 (2): 155–76.