Entrepreneurs spur economic growth and are essential for economic development. According to the WTO, micro firms and small and medium-sized enterprises account for about two-thirds of total employment and a half of GDP, and constitute over 90% of all businesses in OECD high-income countries (WTO 2016). Nevertheless, several decades after the fall of the communist regimes, former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), with the exception of the Baltic states, still lag behind high-income OECD countries in terms of small business development and the ease of doing business. What are the reasons for this relative underdevelopment of entrepreneurial activities in CEE? A burgeoning literature suggests that communism had a number of long-term consequences for socioeconomic outcomes in CEE, including redistribution preferences, corruption, and trust (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln 2007, Ivlevs and Hinks 2018, Nikolova et al. 2019). In a recent study, we complement this literature by documenting that the lack of entrepreneurial activities in CEE countries can be attributed in part to the legacy of the former Communist Party (Ivlevs et al. 2019).

Former Communist Party links continue to influence entrepreneurial outcomes via several channels. First, communist regimes in the CEE forbade private enterprise, owning private property, and market exchange (Aidis et al. 2008, Estrin et al. 2013, Smallbone and Welter 2001). Because communism encouraged state reliance and denounced private initiative, people exposed to it were less likely to have sufficient entrepreneurial skills to start and successfully run businesses after the regime change. Indeed, there is convincing evidence that the former communist regimes substantially shaped individual preferences. For instance, people exposed to communism are more likely to be in favour of state intervention in the economy (Alesina and Fuchs-Schundeln 2007). Second, given the weak institutional environment still eminent in some transition countries, informal networks and the system of mutual favours created by the former Communist Party could have fully or partially substituted for the formal rule of law (Smallbone and Welter 2001, Estrin et al. 2013). Supporting evidence for this channel comes from Djankov et al. (2005), who show that social networks in Russia increase the likelihood of becoming an entrepreneur. These informal networks not only helped former elites in securing capital and resources to start their own businesses, but also helped create barriers to business entry for outsiders (Aidis et al. 2008).

Entrepreneurship trial and success

Based on individual data from Life in Transition Survey-III, in a recent paper (Ivlevs et al. 2019) we find that 5.5% of people across CEE set up and are currently running a business (“Business still active” in Figure 1), 3.6% set up a business in the past that is no longer operational (“Business closed”), 2.4% tried to set up a business but did not succeed (“Failed at setting up a business”), and the remaining 88.5% never tried to set up a business (“Never tried”).

Next to that, our key finding is that having personal or familial links to the former Communist Party has a causal and relatively large effect on some – but not all –entrepreneurial activities. In particular, former Communist Party ties increase the likelihood of having set up a business that is no longer operational by 4.1 percentage points and the likelihood of having unsuccessfully tried to set up a business by 4.1 percentage points; they decrease the chance of having never tried to set up a business by 12.2 percentage points. At the same time, links to the former Communist Party have no effect on having set up and currently running a business. All in all, our results suggest that former Communist Party ties were instrumental for entrepreneurial start-ups in the CEE, but did not guarantee entrepreneurial success and longevity.

Figure 1 Entrepreneurial activity in Central and Eastern Europe

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the LiTS-III.

Notes: The figure shows proportions of the CEE respondents associated with different entrepreneurial outcomes.

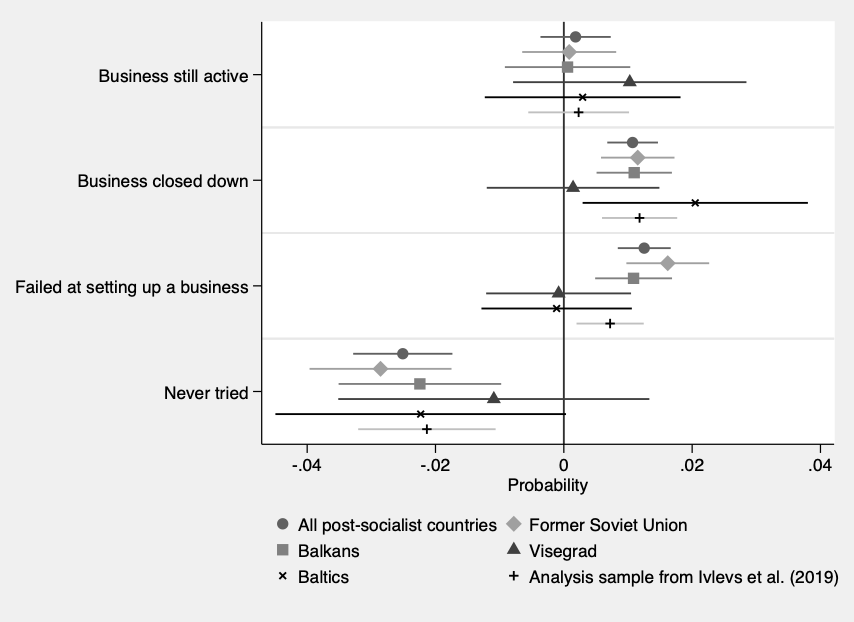

As shown in Figure 2, the relationship between former Communist Party membership and entrepreneurship is nearly universal in the transition region. One exception is that former Communist Party membership is not associated with failing to set up a business in the Visegrad countries (Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary) and in the Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia). To succeed in these countries, nascent entrepreneurs likely did not have to rely on former Communist Party networks, but rather on their past experiences and entrepreneurial skills.

Figure 2 Links to the former Communist Party and present-day entrepreneurial activity

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the LiTS-III.

Notes: The figure shows the effect of former Communist Party membership on the predicted probability of various entrepreneurial activities. The results in the figure adjust for a large number of individual and geography controls. For technical details, see Ivlevs et al. (2019).

We also document that individuals with fewer of the traits associated with entrepreneurship – such as motivation, risk tolerance, and ability – were more likely to join the former Communist Party, while people with former Communist Party links were more likely to believe that success depends on political connections and breaking the law rather than effort and skill.

Therefore, our findings indicate that the least capable Communist Party members (or their children) became entrepreneurs and subsequently closed down their business due to a lack of entrepreneurial talent. In the early stages of democracy, networks, resources, and opportunities provided by former party membership triggered entrepreneurial start-ups by former Communist Party members in CEE.

Implications

Former Communist Party networks still affect business practices in Central and Eastern Europe. This has a number of implications for social welfare and economic development in the region. First, by encouraging a culture of state-reliance rather than personal initiative, communism caused long-lasting damage to entrepreneurship (Alesina and Fuchs-Schundeln 2007). Second, despite its focus on equality and egalitarianism, communism created barriers to entry for business ventures outside party circles, which, paradoxically, laid the foundations for inequality of opportunity when it comes to entrepreneurship. From a social viewpoint, the fact that the least capable former Party members started businesses and subsequently failed, while also possibly crowding out those without elite connections, suggests a social welfare loss. Since entrepreneurship is one of the main drivers of economic growth, ensuring a level playing field and reducing barriers to entrepreneurship for all should be a policy priority in countries undergoing political and economic regime change.

References

Aidis, R, S Estrin and T Mickiewicz (2008), “Institutions and Entrepreneurship Development in Russia: A Comparative Perspective”, Journal of Business Venturing 23(6): 656-672.

Alesina, A and N Fuchs-Schundeln (2007), “Good-Bye Lenin (or Not?): The Effect of Communism on People’s Preferences”, The American Economic Review 97(4): 1507-1528.

Djankov, S, E Miguel, Y Qian, G Roland and E Zhuravskaya (2005), “Who are Russia’s Entrepreneurs?”, Journal of the European Economic Association 3(2-3): 587-597.

Estrin, S, J Korosteleva and T Mickiewicz (2013), “Which Institutions Encourage Entrepreneurial Growth Aspirations?”, Journal of Business Venturing 28(4): 564-580.

Ivlevs, A, M Nikolova and O Popova (2019), “Former Communist Party Membership and Present-Day Entrepreneurship in Central and Eastern Europe”, IZA Discussion Paper 12761.

Ivlevs, A and T Hinks (2018), “Former communist party membership and bribery in the post-socialist countries”, Journal of Comparative Economics 46: 1411-1424.

Nikolova, M, O Popova and V Otrachshenko (2019), “Stalin and the Origins of Mistrust”, IZA Discussion Paper 12326.

Smallbone, D and F Welter (2001), “The Distinctiveness of Entrepreneurship in Transition Countries”, Small Business Economics 16(4): 249-262.

WTO (2016), Levelling the Trading Field for SMEs, World Trade Report.