Over the past 30 years, most central banks across the advanced economies have been given the ability to conduct monetary policy independently from interference by fiscal and political authorities (Crowe and Meade 2007). Today, almost all central banks in OECD countries are operationally instrument-independent, counting on their own tools to set or target several interest rates, even if none of them is goal-independent, since political bodies give them their mandate.

Closely related to central bank independence has been the adoption of inflation targeting as a policy framework, whereby central banks announce their target for inflation in the near or medium term, and transparently describe their different policy choices with respect to the target (Svensson 2010). Empirical work has measured independence using a variety of different indicators. The more commonly used include:

- the rules for appointment and dismissal of central bank governors;

- the extent to which the government or fiscal authorities must be consulted before monetary policy decisions;

- whether the goals of the central bank are wide-ranging or tightly focused on what the central bank can achieve; and

- the ability of the central bank to finance its operations without relying on the government.

Research has also emphasised the importance of transparency and accountability of the central bank, the ability of the central bank to use its balance sheet, and the extent to which the central bank counts on fiscal backing and the rules for distribution of its revenues (Reis 2013). As a result, central bank independence is not a binary outcome of either independent or not, but rather can increase or decrease in a more continuous fashion.

Empirical evidence has supported the institutional changes that have given central banks greater independence. An influential study by Alesina and Summers (1992) showed that central bank independence was associated with lower inflation on average, without any significant increase in unemployment or volatility. And summarising a long research literature on the topic, Cukierman (2008) said that “the evidence is consistent with the conclusion that inflation and actual [independence] are negatively related in both developed and developing countries”.

Partly driven by these results, the argument for independence has been extended to other realms of economic policymaking. For example, the IMF documents 39 independent fiscal councils that publicly assess fiscal plans, budget forecasts, and policy implementation and performance (IMF 2016).

At the same time, central banks have embraced – more or less reluctantly – roles for financial stability and the use of macroprudential policies, where some cooperation with other public authorities is needed and which have clear distributional implications. This has created institutional pressures for central banks to be less independent.

Will central bank independence continue?

In spite of an academic consensus on the value of central bank independence and a three-decades-long movement towards greater independence, there are some signs that this trend may reverse in the near term. The vice chair of the Federal Reserve, Stanley Fischer, recently described the many current challenges to central bank independence (Fischer 2015).

As central banks have assumed wider responsibilities for financial stability, used unconventional instruments and acted with a great deal of discretion during the global financial crisis, these controversial choices have been subject to political scrutiny and disagreement (Cochrane and Taylor 2015). More recently, discussions of explicit fiscal measures by the central bank, such as helicopter drops of money, have led to increasingly critical voices of central banks as overstepping their mandates.

Some academics have even wondered whether central bank independence is already dead (Baldwin and Reichlin 2013). Among policymakers, Abenomics in Japan involved significant intervention by political authorities over the target and actions of the Bank of Japan. In the Eurozone, only 30% of Germans trust the European Central Bank (ECB), according to the Eurobarometer survey of public opinion, and the ECB’s rescue operations have led to questions about its independence (Reuters 2015).

In the UK, some commentators have been critical of governor Mark Carney’s involvement in the Brexit debate, and senior figures in both major political parties have written public pieces criticising the Bank of England’s independence (Balls et al. 2016; Hague 2016). These critiques by politicians receive much media coverage.1

Finally, in the United States, president-elect Donald Trump frequently criticised the Federal Reserve during the election campaign, and members of congress have argued that the House should have more oversight over the activities of the central bank. Some of these criticisms contradict each other, but together they form a tide of opinion questioning the independence of the central bank.

Can we expect the era of central bank independence to come to an end or at least to be modified in a substantial way? Is this possibility real not only in Japan but also in Europe? That is the focus of the first question in the latest CFM-CEPR expert survey. Given that our panel consists of economists based in Europe, who are thus most capable of understanding the political and institutional environment in Europe, the focus is on the ECB and the Bank of England.

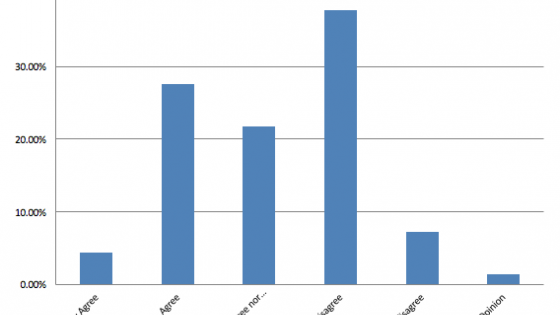

Question 1: Do you agree that central bank independence in the Eurozone and the UK will decline over the next 48 months?

Seventy panel members answered this question. The panel members are roughly evenly divided, with a minority of 32% that either agrees or strongly agrees, a larger minority of 45% that either disagrees or strongly disagrees, and a large fraction of 22% that neither agrees nor disagrees. Given that central bank independence has been largely uncontroversial for a long period, it is remarkable that a substantial fraction of our experts now think that there could be serious changes in central bank independence.

In spite of the evenly distributed final responses, the comments made by the experts provide a more united view. Many of them acknowledge that there will be pressures challenging central bank independence. The disagreement mainly lies in whether the pressure will be strong enough and whether it will last long enough to make a difference. An exception is David Miles (Imperial College London), who argues that “some of what appear to be criticisms of central banks is not so much a threat to their independence but more a questioning of the goal they are set”.

Several panel members point out that institutional aspects make it less likely that the independence of the ECB will be affected in the near future than the independence of the Bank of England. For example, Sean Holly (University of Cambridge) writes “according to the Maastricht Treaty ‘neither the ECB, nor a national central bank, nor any member of their decision-making bodies shall seek or take instructions from Community institutions or bodies, from any government of a Member State or from any other body’. Any such revision of the Treaty would require the agreement of all EU members, not just those part of the Euro Area. This is not going to happen over the next four years. … However, the case of the UK is a different matter. An Act of Parliament revoking Bank of England operational independence could go through Parliament in an afternoon.”

Some panel members believe that independence may also be affected by more subtle pressures. Lars Svensson (Stockholm School of Economics) points out that “[o]ne has to distinguish de jure and de facto central bank independence. I do not think de jure independence will decline in the next four years in the Eurozone and the UK. However, political pressure on central bank policy may increase, and that may marginally affect central bank policy, so in that sense de facto independence may decline somewhat.”

Some respondents think that political pressures have already affected central bank independence. Jürgen von Hagen (Universität Bonn) argues that “[u]nder President Draghi, the ECB’s independence has proven to be very low already in past years. The ECB has consistently done what was politically convenient.” Similarly, Panicos Demetriades (University of Leicester) says that “the independence of central banks has been eroded through political capture of central bank boards and other indirect actions by governments”.

Our experts distinguish three different reasons why central bank independence is currently being challenged.

The first reason is populism. Ricardo Reis (London School of Economics, LSE) writes “the rise of populism in the Western world in 2016, the recent electoral success of authoritarian politicians, and the public relations campaign against experts and knowledge, all point to pressure on attacking independent technocratic institutions and reducing their power, including the central bank”.

At the same time, several panel members point out that political forces are hard to predict. Albert Marcet (Institut d’Analisi Economica, Barcelona) comments that “because of the crisis all institutions are in question, including central banks, but I doubt a clear constituency against their current role will emerge. But then, so many weird things have been happening in politics that who knows.”

The second reason for central bank independence being challenged is a changing landscape in terms of the overall economy and central banks’ responsibilities relative to the times when their independence took off. Martin Ellison (University of Oxford) notes that “the original rise in central bank independence was motivated by successful taming of inflation in the 1980s”.

Andrew Mountford (Royal Holloway) goes even further, arguing that “central bank independence only makes sense within a mindset of a stable balanced economy where the only implication of too lax a credit policy is inflation”. But times have changed and as Pietro Reichlin (LUISS, Università Guido Carli) remarks, “since 2008, the ECB’s objectives have expanded from inflation targeting to financial stability, prevention of speculative attacks on sovereign debt, liquidity provision to national banks in peripheral countries and quantitative easing”.

Several panel members think that such changes will affect central bank independence. For example, Sylvester Eijffinger (Tilburg University) suggests that “the unprecedented size of the central bank balance sheets in the Eurozone and the UK has far-reaching implications for the financial dimension of central bank independence by the monetary financing of government debt undermining the credibility and independence of the central banks. The threat of fiscal dominance with monetary accommodation is particularly strong in developed countries (the Eurozone and the UK) with high public debt levels.”

More generally, Jagjit Chadha (National Institute of Economic and Social Research) points out that “[o]nce the central bank gets involved in more than one objective, trade-offs may start to appear and some discussion of the social welfare function may be needed”.

The third reason for the challenge to independence is a loss of credibility due to recent policies that central banks have pursued. Several panel members choose strong wordings to characterise recent central bank actions and policies. For example, Fabrizio Coricelli (Paris School of Economics) says that “credibility of ECB policies is undermined by the past several years of erratic policy and several commitments to do ‘whatever it takes’”.

Patrick Minford (Cardiff Business School) argues that “central banks allowed a sizeable credit boom to develop in the run-up [to the financial crisis]; they failed to resolve the resulting contraction by providing sufficient liquidity to the banking system and the Lehman collapse resulted, triggering the acute crisis downturn; afterwards central banks coordinated around a massive regulatory backlash which prevented the recovery of credit and worsened the crisis recovery process badly. These actions have badly shaken confidence in central banks’ competence.”

Is central bank independence still important for low and stable inflation?

Inflation has been running below target and is expected to do so in the near future, yet conventional theory (still) predicts that independent central banks setting interest rates are able to control inflation (Reis 2016). Because in most well-specified models inflation is the result of an interaction between monetary and fiscal policy, looking into the future, perhaps the way to have inflation rise is for fiscal policy to be more active, effectively reducing central bank independence (Sims 2016).

Theory and evidence (described in the background information above) indicate that giving independence to the central bank lowers inflation expectations and inflation itself. Most of the theoretical arguments are symmetric, suggesting that if central bank independence declines, inflation should rise.

At the same time, the symmetry comes from assuming linear models, but this may have been the result of modelling convenience. Moreover, the arguments rely on the effect of institutions on expectations, and there is enough uncertainty on how best to model expectations to not be overly confident that they will move symmetrically.

Question 2: Do you agree that the traditional argument that less central bank independence leads to higher inflation will (still) be relevant over the next 48 months in Western economies?

Seventy panel members answered this question. Again, the panel members seem divided with a minority of 34% that either disagrees or strongly disagrees and a larger minority of 48% that either agrees or strongly agrees. It is again remarkable that a proposition that has been taken for granted in the academic literature for a considerable period can no longer count on a clear majority.2

The panel members who agree provide few comments and those who do mostly claim that traditional arguments still apply. For example, John Driffill (Birkbeck, University of London) writes that “the argument will remain relevant, despite weak demand in the Eurozone and Japan. If populist governments in the US or UK get more control of monetary policy, there may be no danger of higher inflation in the short run, but it would bring risks of inflation further into the future.”

Sir Christopher Pissarides (LSE) argues that financial markets would be the first to react to any reduction in independence: “financial markets will interpret it as political meddling with inflation targets and will adjust inflation expectations upward. This will be immediately reflected in lower real interest rates.”

Those who disagree provide a wider range of arguments. Several experts point out that inflation is unlikely, even with central banks becoming less independent because of the weak state of the economy, and that it would take something else to trigger inflation. Jonathan Portes (King’s College London) says that “[t]he traditional frame is increasingly irrelevant. Higher inflation has not been a problem – quite the opposite – in advanced economies for most of the last decade.”

Others argue that central banks’ influence on inflation is limited in the current state of the world. Per Krusell (Stockholm University) writes that “[t]he difference is unlikely to be small, given that the central banks have shown limited ability to affect inflation in the current low-interest rate regime”.

A different set of arguments points to the interaction of independence with other features that would determine whether inflation rises or falls. Lars Svensson points to transparency: “it seems that pressure to deviate from the inflation target may be in either direction, not necessarily always to exceed the target. … central bank independence must be accompanied by sufficient central bank accountability to achieve the democratically determined objectives of monetary policy.”

Jordi Gali (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) comments on the role of fiscal policy as being more important: “A more expansionary fiscal policy, supported by monetary policy, would be a more suitable way to tighten labour markets and capacity and raise inflation where it needs to.”

Martin Ellison notes that political pressures do not always lead to more expansionary monetary policies as indicated by the traditional reasoning. He writes that “if central bank independence falls, then people like former Conservative Party leader William Hague will have more influence. He wants interest rates to rise to reward savers, but if this happens then inflation would actually turn out to be lower than it would be under a fully independent Bank of England.”

Similarly, John Muellbauer (University of Oxford) says “there are different counterfactuals, and the answer would then depend very much on the nature of the reduction in central bank independence. For example, if the ban on monetary finance of the fiscal authorities were removed, this might change the long-term inflation outlook. But if an independent ECB remained the guardian of when such monetary finance were offered, I see little reason why worries about inflation should increase.”

Is central bank independence desirable?

The institutional shift towards greater central bank independence followed a successful theoretical literature that began 40 years ago. The influential Nobel Prize-winning work of Kydland and Prescott (1977), followed by research by Barro and Gordon (1983), argued that if central banks were dependent on politicians, then there would be a bias towards higher inflation without any corresponding benefit. Politicians would be tempted to set looser policy and unexpectedly increase inflation in order to lower unemployment via the Phillips curve.

Aware of this temptation, people would have higher inflation expectations, which would lead to higher inflation without any gains in employment. Likewise, fiscal authorities would be tempted to inflate away the debt, leading to a large inflation premium paid on the borrowing costs of the government. Everyone would be better off if an independent authority were able to commit credibly to not increasing inflation, and central banks could be naturally designed with this goal.

Further arguments have been put forward for central bank independence over the years. For example, independent central banks are less prone to fund fiscal deficits via seigniorage, which is the common harbinger of hyperinflations (Cagan 1956).

An independent central bank may also be the optimal answer to the political economy equilibrium between different public policy bodies with different expertise and effects on the income distribution (de Haan and Eijffinger 2016). In the Eurozone, the ECB’s independence is tied to independence from national policymakers, and further arguments for it are that it is able coordinate policies across countries and to internalise macroeconomic externalities across countries.

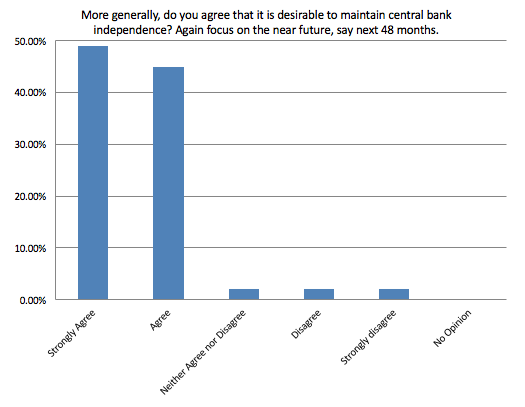

Question 3: More generally, do you agree that it is desirable to maintain central bank independence in the future?

On this normative question, the panel members responded with almost unanimity and great confidence. Of the 49 panel members who answered this question, 46 either agreed or strongly agreed. Only one neither agreed nor disagreed, another disagreed, and a third strongly disagreed.

Several experts mention the traditional argument that too much political influence will lead to expansionary policies that lead to higher inflation and at best some short-term increase in real activity. As Michael McMahon (University of Warwick) writes, “monetary policy independence should be maintained to avoid concerns that that government is trying to regain control of monetary policy for such manipulation”.

Francesco Lippi (Università di Sassari) points to the difference in horizon as a fundamental reason why independence must remain: “Central bank independence is useful because monetary policy decisions are for the medium run, a horizon for which the typical policymakers are not well equipped. The central bank’s ex-post accountability ensures the process remains ultimately accountable to the citizens.”

The discussion above makes clear that our experts think that there are serious challenges to central bank independence and that the current economic environment is quite different to the one that led to central bank independence.

Some repeat their desire for an improvement in current arrangements. Jordi Gali comments, “Appointments of governors/presidents are still too partisan in many countries. Parliamentary hearings, possibly with the participation of external experts, and a significant multi-partisan support for a candidate, would be highly welcome.” John Hassler (Stockholm University) writes that “[i]t needs to be clarified that the broad measures with substantial fiscal components used during the Great Recession cannot permanently be in the hands of an independent central bank.’

Nevertheless, an overwhelming majority still favours central bank independence. Gali unequivocally states that “[c]entral bank independence, combined with a high level of transparency and accountability, is in my view the best arrangement for advanced economies”.

Others argue that central bank independence has a proven track record. For example, Ricardo Reis says that “among all economic policymaking institutions in most advanced countries today, central banks tend to be the better prepared, the better informed, and make the more sensible decisions. Their success at keeping inflation close to targets in the past 15 years has been extraordinary. Their responses to the financial and debt crisis were, with all their flaws and shortcomings, still much better than that of almost all other policy institutions. I am worried that there has been too much discretionary policymaking, and too quick an embrace of financial stability as a goal that can be achieved by the central bank alone. But for now, the track record of independent central banks is very good.”

In contrast, the very few who disagree reject the validity of independent institutions making choices with political consequences. Andrew Mountford argues that “the control of the amount of credit in the economy and the control of the banking sector more generally is intrinsically political. … The idea that control of this sector should be removed from government and thus ultimately from accountability to those that the system is supposed to work for (the general public) is economically ludicrous … and politically terrifying.”

References

Alesina, A, and L Summers (1993), ‘Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 25(2): 151-62.

Baldwin, R, and L Reichlin (eds) (2013), Is Inflation Targeting Dead? Central Banking After the Crisis, CEPR Press.

Balls, E, J Howat and A Stansbury (2016), ‘Central Bank Independence Revisited: After the Financial Crisis, What Should a Model Central Bank Look Like?’, Harvard Kennedy School Mossavar-Rahmani Centre for Business and Government Associate Working Paper No. 67.

Barro, R, and D Gordon (1983), ‘Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy’, Journal of Monetary Economics 12(1): 101–21.

Cagan, P (1956), ‘The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflations’, in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money edited by Milton Friedman, University of Chicago Press.

Cochrane, J, and J Taylor (2016), Central Bank Governance And Oversight Reform, Hoover Institution.

Crowe, C, and E E Meade (2007), ‘The Evolution of Central Bank Governance around the World’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(4): 69-90.

Cukierman, A (2008), ‘Central Bank Independence and Monetary Policymaking Institutions – Past, Present and Future’, European Journal of Political Economy 24(4): 722-36.

De Haan, J, and S Eijffinger (2016), ‘The Politics of Central Bank Independence’, in Handbook of Public Choice, Oxford University Press.

Fischer, S (2015), ‘Central Bank Independence’, speech, 4 November.

Hague, W (2016) Central bankers have collectively lost the plot. They must raise interest rates or face their doom, The Telegraph 18 October.

IMF (2016) Fiscal Council Dataset.

Kydland, F, and E Prescott (1977), ‘Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans’, Journal of Political Economy 85(3): 473-92.

Reis, R (2013) ‘Central Bank Design’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(4): 17-44.

Reis, R (2016), ‘Funding Quantitative Easing to Target Inflation’, in Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future, Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Reuters (2015), "Cracks showing in Germany’s fragile truce with the ECB", 25 September.

Sims, C (2016), ‘Fiscal Policy, Monetary Policy, and Central Bank Independence’, in Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future, Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Svensson, L (2010), ‘Inflation Targeting’, in Handbook of Monetary Economics Volume 3B edited by Benjamin M. Friedman and Michael Woodford, Elsevier.

Endnotes

[1] See http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-38010222 and https://www.ft.com/content/2616611e-a665-11e6-8b69-02899e8bd9d1.

[2] If we weigh the answers with self-assessed confidence, then the fraction of panel members who agree or strongly agree increases to 52%. If we exclude the panel members who neither agree nor disagree, then a majority of 60% agrees or strongly agrees.