Women have been facing significant barriers to their economic inclusion (World Bank 2021). And in some economies, the pandemic has exacerbated existing gender gaps (Alon et al. 2020, Taneja et al. 2021). Yet in the area of women’s emancipation, there is a long history of scepticism regarding the relevance of laws that discriminate on the basis of gender (Cascio and Shenhav 2020), reflecting the view that de jure changes are often not informative about de facto changes. While several studies have analysed the link between laws and women’s economic outcomes using data from individual countries (for example, Combs 2005, Deininger et al. 2013, and Hazan et al. 2019), we put this view to the test using a global database of legal gender equality (described in Hyland et al. 2020). We first ask which factors explain the variation in legal gender equality across countries, and then ask whether this de jure measure of equality correlates in a meaningful way with several de facto measures of women’s economic empowerment. The implications of this research are far-reaching, as women’s empowerment and gender diversity are associated with long-run economic growth (Baten and de Pleijt 2019, Lagarde and Ostry 2018).

Country characteristics that evolve slowly, or not at all, are strong predictors of legal equality between men and women

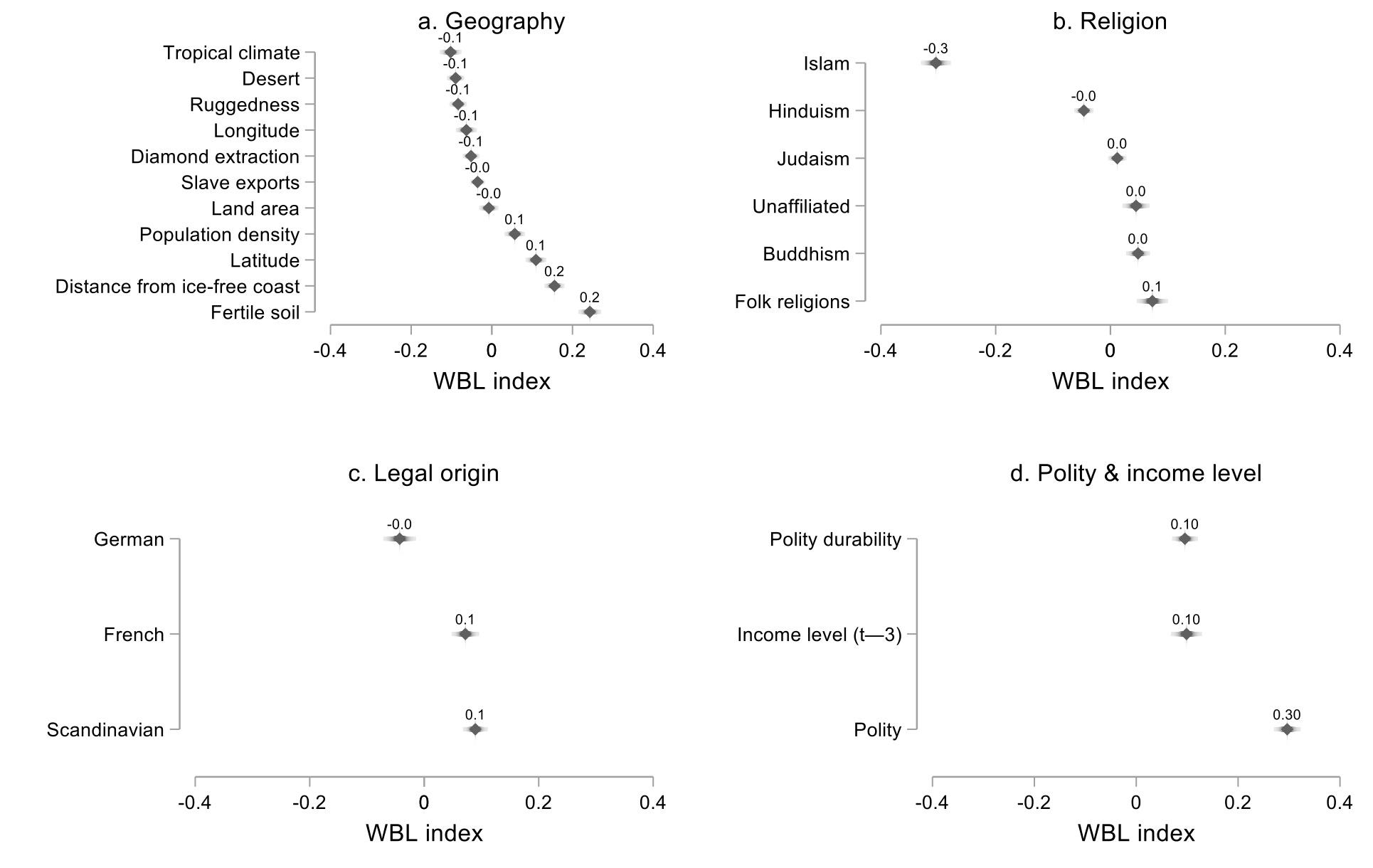

In a new paper (Hyland et al. 2021), we find that legal equality is correlated with countries’ geographic characteristics, and that the associations hold even after controlling for real income per capita (Figure 1, Panel A). Our results show that religion is also a significant predicator of gender equality. Relative to countries in which the main religion is Christianity (the reference category), countries in which the main religion is a folk religion, Buddhism or Judaism, and countries with no official religion have higher gender equality; countries in which the main religion is Hinduism have slightly lower levels of gender equality, and countries that are predominately Muslim are characterized by significantly lower levels of gender equality (Figure 1, Panel B).

A country’s legal origin is a significant predictor of legal gender equality (Figure 1, Panel C). Economies with French or Scandinavian legal origins have more gender-equal laws than those based on the English common law system (the reference category). This is unsurprising as countries whose legal origin was based on common law adhered – in some cases for several centuries – to the doctrine of couverture, whereby upon marriage, a woman’s legal rights were subsumed by her husband. We also find that more democratic systems of government are associated with greater legal equality between genders (Panel D).

Figure 1 Correlation between geography, religion, legal origin, and polity and income level with the Women, Business and the Law (WBL) index

Source: Authors’ calculations.

The analysis of the links between country characteristics and legal gender equality yields two major insights. First, approximately 70% of the variation in legal equality between countries is explained by the characteristics presented in Figure 1. Second, almost all of the statistically significant characteristics presented in Figure 1 evolve either slowly or not at all. This may make one pessimistic about the prospect of change. Nevertheless, as we show in earlier work (Hyland et al. 2020), considerable progress in legal gender equality has taken place over the past half century. Laws may be slow to change, but they do change. However, do such changes translate to meaningful improvements in women’s lives?

Legal equality between men and women is correlated with women’s empowerment

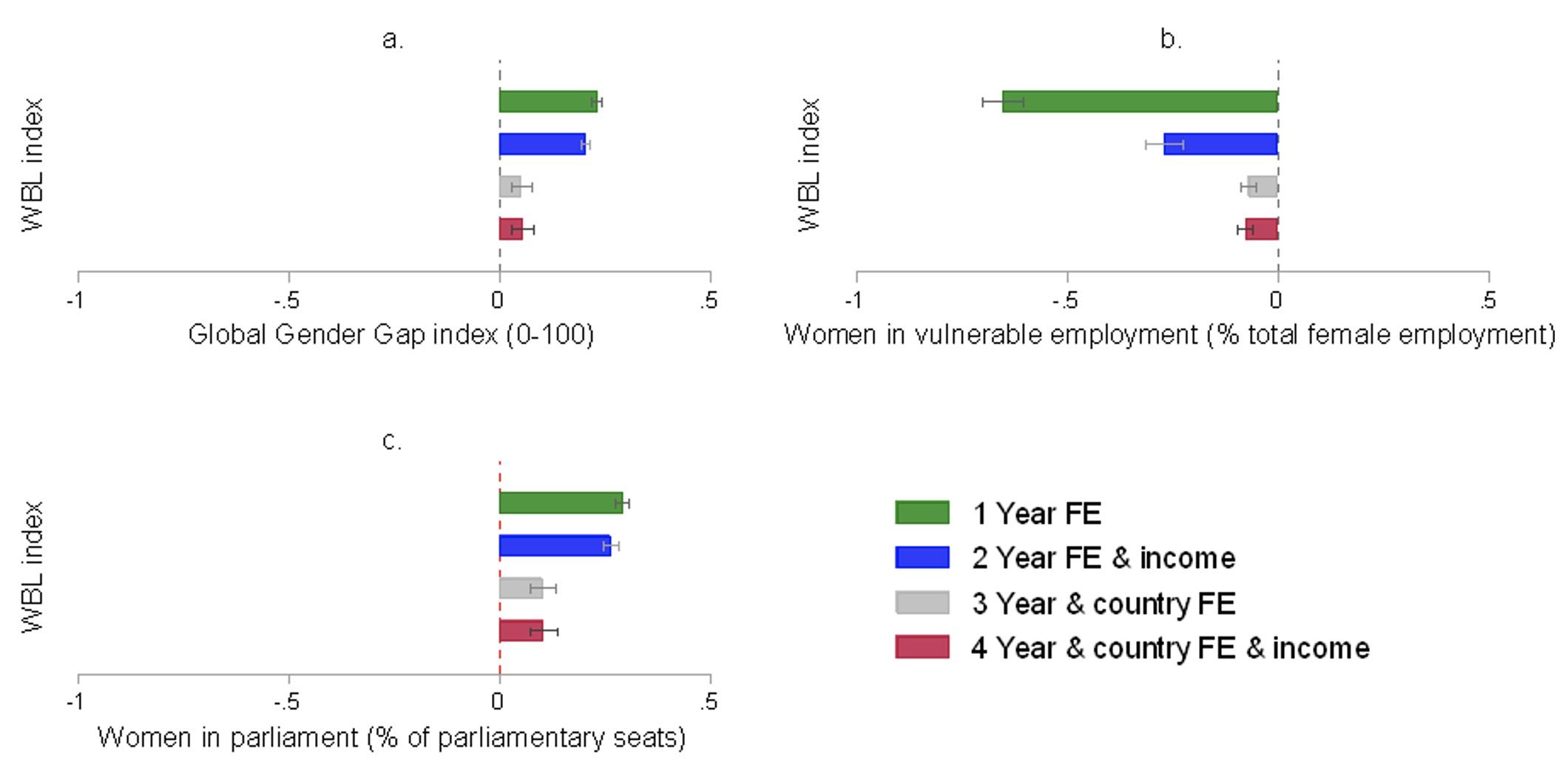

We investigate the relationship between equality and empowerment using three broad measures. The first is an aggregate measure of the gap between women and men in outcomes and opportunities computed by the World Economic Forum and published annually in their Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum 2019). The second is female employees’ propensity to be in positions of vulnerable employment as opposed to wage and salaried jobs; these workers are the most likely to fall into poverty, the least likely to have access to social protection and safety nets, and the least likely to be in a position to save. The third is women’s representation in national parliaments, as recorded by the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Figure 2 Correlation between the Women, Business and the Law (WBL) index and the gender gap in outcomes, women in vulnerable employment, and women’s representation in parliament

Source: Authors’ calculations.

We find that higher legal equality is associated with a narrower gender gap in opportunities and outcomes, with fewer women in positions of vulnerable employment, and with greater political representation for women (Figure 2). These results are robust to conditioning on the level of economic development as proxied by GDP per capita. Moreover, they are robust to conditioning on country fixed effects, where the association between laws and outcomes is identified based on variation over time within each country rather than on cross-country comparisons. While the magnitudes of the correlations are small once year and country fixed effects, as well as income level are accounted for (the fourth bar in Panels A, B, and C of Figure 2), legal discrimination represents only one form of discrimination that a woman may face. Furthermore, these indicators of inclusion and empowerment move slowly; for example, the average annual global increase in women’s political representation in parliament since 1998 is only 0.56 percentage points.

These associations provide reasons for optimism since law changes are actionable. The fact that, according to our analysis, legal reforms are correlated with important metrics of women’s empowerment, implies that changes in the law, however slow these may be, translate to real change and serves as an important motivating factor to abolish legal discrimination against women.

References

Alon, T, M Doepke, J Olmstead-Rumsey, and M Tertilt (2020), “The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality,” Covid Economics 4.

Baten J and A de Pleijt (2019), “Female autonomy generates superstars in long-term development: Evidence from 15th to 19th century Europe”, VoxEU.org, 11 February.

Cascio, E U and N Shenhav (2020), “A Century of the American Woman Voter: Sex Gaps in Political Participation, Preferences, and Partisanship Since Women’s Enfranchisement”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(2): 24-48.

Combs, M B (2005), “A Measure of Legal Independence: The 1870 Married Women’s Property Act and the Portfolio Allocations of British Wives”, Journal of Economic History 65(4): 1028-57.

Deininger, K, A Goyal, and H Nagarajan (2013), “Women’s Inheritance Rights and Intergenerational Transmission of Resources in India,” Journal of Human Resources 48(1): 114-41.

Hazan, M, D Weiss, and H Zoabi (2019), “Women’s liberation as a financial innovation”, VoxEU.org, 23 March.

Hyland, M, S Djankov, and P K Goldberg (2020), “Gendered Laws and Women in the Workforce”, American Economic Review: Insights 2(4): 475-90.

Hyland, M, S Djankov, and P K Goldberg (2021), “Do gendered laws matter for women’s economic empowerment?”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper.

Lagarde, C and J D Ostry (2018), “The macroeconomic benefits of gender diversity”, VoxEU.org, 05 December.

Taneja, S, P Mizen, and N Bloom (2021), “Working from home is revolutionising the UK labour market”, VoxEU.org, 15 March.

World Economic Forum (2019), Global Gender Gap Report 2020.

World Bank (2021), Women, Business and the Law 2021.