The global financial crisis that originated in the advanced economies has dealt a severe blow to growth in the rest of the world over the last two years. But why did some countries fare better than others?

To examine this question, researchers have started to take a look at the cross-country evidence:

- The World Bank (2009) has examined the structural factors that could help explain the change in actual growth in 2007 and projected growth in 2009. Given that many countries were expected to experience a sharp slowdown even prior to the crisis, this approach does not provide a clean picture of the distribution of growth collapses attributable to the global shock.

- Meanwhile, Berglöf, Korniyenko, and Zettelmeyer (2009) analyse the effects of the global financial crisis on growth in emerging Europe. Using actual growth rates (instead of forecast revisions) for a limited set of countries, they find that external debt liabilities, a decline in export volumes in the fourth quarter of 2008, real effective exchange rate appreciation relative to 2002, foreign direct investment liabilities as a share of GDP, and political instability tended to add to the depth of the output declines between 2008 and 2009.

- Finally, Rose and Spiegel (2009) find no evidence that international linkages have an impact on the incidence of the crisis.

The forecast-revision approach

In recent research (Berkmen et al. 2009), we have taken a somewhat different approach. We focus on revisions in GDP growth forecasts before and after the crisis for a sample of 40 emerging market countries and for a larger sample of 126 developing countries, including emerging markets. We then assess the importance of a wide range of factors that could explain differences in the size of these forecast revisions. Using forecast changes allowed us to bypass many otherwise difficult issues – for example, to control for differences in growth rates that are due to differences in levels of development or cyclical positions, or other factors unrelated to the impact of the crisis. In addition, it allows us to incorporate the expected short-term effects of policies.

Emerging markets

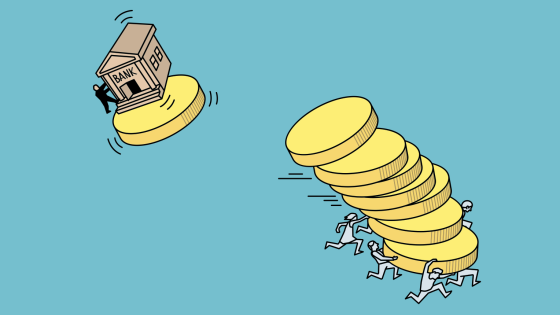

For the 40 emerging markets, financial factors appear to have been key in determining the size of the growth revision. In particular, countries that experienced strong credit booms were more vulnerable to the slowdown. Leverage – measured as the credit to deposit ratio – and cumulative credit growth, turn out to be significant explanatory variables across various specifications.

For the most part, countries with pegged exchange rates experienced larger downward growth revisions (on average, in excess of two percentage points) compared to countries with more flexible exchange rates. None of the least-affected countries in the sample had a pegged exchange rate.

The stock of international foreign exchange reserves – measured in numerous ways – did not have a statistically significant effect on the growth revisions (Blanchard 2009 reports finds similar results). This may reflect the fact that the benefits of international reserves may diminish sharply once they grow above a level considered sufficient to guard against risks. Several of the countries that had the largest growth revisions, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, had levels of international reserves similar to those prevailing in some of the less-affected countries in Europe or Latin America.

On fiscal policy, while the evidence is somewhat less robust, there is some indication that the primary fiscal gap (the difference between the actual primary balance and the one consistent with keeping public debt constant as a share of GDP) is positively associated with better growth performances. This is in line with the idea that countries which had conducted prudent fiscal policies prior to the global crisis were less prone to confidence crises and were in better position to adopt stimulus measures during the slowdown.

Leverage explains virtually all of the growth revision for the least-affected emerging market countries in the sample, roughly two thirds of the revision for the average emerging market country, and slightly more than half of the revision for those countries most affected by the crisis. Credit growth explains a significant share of the growth revision for the average country as well as those most affected.

Trade linkages

We also examine growth revisions for a larger group of developing economies (including emerging markets) to explore whether other channels, such as trade linkages, mattered for a broader set of countries.

Interestingly, the trade channel appears to matter in this sample, although not for emerging markets. Although the degree of trade openness does not appear to be decisive, the composition of trade does make a significant difference. In particular, the share of commodities (both food and overall) in total exports is associated with smaller downward growth revisions. The share of manufacturing products in total exports is correlated with worse growth performance both for advanced and developing countries. This is consistent with the notion that countries exporting manufacturing goods to advanced countries seem to have been hit hard by the decline in demand from these markets, while countries exporting food appear to have fared better.

More generally, the results are in line with the intuition that the transmission of shocks to countries with lower financial linkages to the world (such as low-income countries) tend to occur predominantly through trade, while the financial channel is more relevant for countries with close financial ties to the advanced economies, where the crisis originated.

Policy lessons

The evidence suggests drawing some – preliminary – policy lessons:

- Exchange-rate flexibility is crucial to dampen the impact of large shocks;

- Prudential regulation and supervision need to focus on preventing the build-up of vulnerabilities that are particularly associated with credit booms, such as excessive bank leverage;

- A solid fiscal position during “good times” creates some buffers to conduct countercyclical fiscal policies during shocks.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management

References

Berkman, Pelin, Gaston Gelos, Robert Rennhack, and James P Walsh (2010), “The Global Financial Crisis: Explaining Cross-Country Differences in the Output Impact”, IMF Working Paper WP/09/280.

Berglöf, Erik, Yevgenia Korniyenko, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer (2009), “Crisis in Emerging Europe: Understanding the Impact and Policy Response,” unpublished manuscript.

Blanchard, Olivier (2009), “Global Liquidity Provision”, presentation given at the Jornadas Monetaria y Bancarias of the BCRA (Argentina).

Rose, Andrew K. and Mark M Spiegel (2009), “Cross-Country Causes and Consequences of the 2008 Crisis: International Linkages and American Exposure”, NBER Working Paper 15358.

World Bank (2009), “Update on The Global Crisis: The Worst is Over, LAC Poised to Recover”, Office of the Regional Chief Economist (Washington: The World Bank Group).