Historically, governments have relied on economic sanctions to defend their actual and/or perceived national interests in their dealings with foreign competitors or adversaries. But the form that international sanctions take, their frequency, and coverage vary substantially across time and across targeted countries and groups. Further, the motivation and objectives of sanction policies are fairly heterogenous. Finally, the efficacy of sanctions is a controversial topic that is discussed heatedly by policymakers and researchers alike (Crozet et al. 2021, Dizaji and van Bergeijk 2013).

Despite the controversy surrounding the success of sanction policies (van Bergeijk 2012), in recent years the world has experienced a strong rise in their use. Along with its protectionist trade policies, the Trump administration has accelerated the implementation of unilateral sanction policies against other countries (such as Venezuela, Iran, North Korea, and Russia). In fact, President Trump imposed sanctions at a record-shattering rate, more than any other president in US history. At the same time, other large countries (or groups of countries), such as China and the EU, have followed this policy trend.

Motivated by these developments, in 2016 we initiated the creation of the ‘Global Sanctions Data Base’ (GSDB 2021, Kirilakha et al. 2021). The first version of the database was published in 2020 (Felbermayr et al. 2020a, 2020b). In the initial setup phase, sanction cases were collected from a limited number of sources with a focus on the years 1950-2016. Multilateral sanctions, which were mostly based on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolutions, were collected from publicly available UN documents. For the US and the EU, policy orders and corresponding national sources were screened. Additionally, for each individual country in the database, national sources were searched to identify additional cases. Likewise, international newspapers and history books were screened and keyword web searches in online search engines were consulted to identify country specific sanctions. With this procedure we were able to identify a total of 729 sanction cases.

The coverage of the recently updated database (version 2) has improved it in two ways. First, due to the discovery of new sources for sanctions and the improved listings in public databases, the Global Sanctions Data Base now identifies additional cases for the period 1950-2016. Second, the updated database covers an additional three years (i.e. from 2016-2019).

As a result, the new version lists a total of 1,101 publicly traceable, multilateral, plurilateral, and unilateral sanction cases over the period 1950-2019.

There are several reasons for the increase in the number of sanction cases in our first update of the database. First, we relied on additional new sources. Most notably, we utilised the ‘Sanctions Alert’ for new sanctions imposed between 2013 and 2017. Second, we managed to record additional sanction cases (primarily related to financial and military aid cuts, travel bans, and diplomatic sanctions) by relying on the ‘Intrastate Dispute Narratives of the Dynamic Analysis of Dispute Management’ (DADM) project, led by the political science department at the University of Central Arkansas. Third, we revisited existing sanction databases and, once again, cross-checked our cases against them. In particular, we studied in detail each sanction case in Hufbauer et al. (2007). Within a number of sanction policies, we identified additional cases. We also cross-checked with Morgan et al. (2014) for missing cases (mostly for the 1950-1990 period). Fourth, we compared the cases in the Global Sanctions Data Base with newly constructed datasets (i.e. the EUSANCT database by Weber and Schneider (2020)). Lastly, we included several cases per suggestions that we received from some users of the Global Sanctions Data Base.

In the update we discovered 306 additional cases that were imposed up to 2016, and 75 new cases imposed during 2016-2019.

In the database, sanction cases are classified into distinct types, including trade sanctions, financial sanctions, travel restrictions, arms sanctions, military assistance sanctions, and other types of sanctions. For each case, the database identifies policy objectives that appear in official documents. Finally, the database assesses the success of each sanction case in four categories.

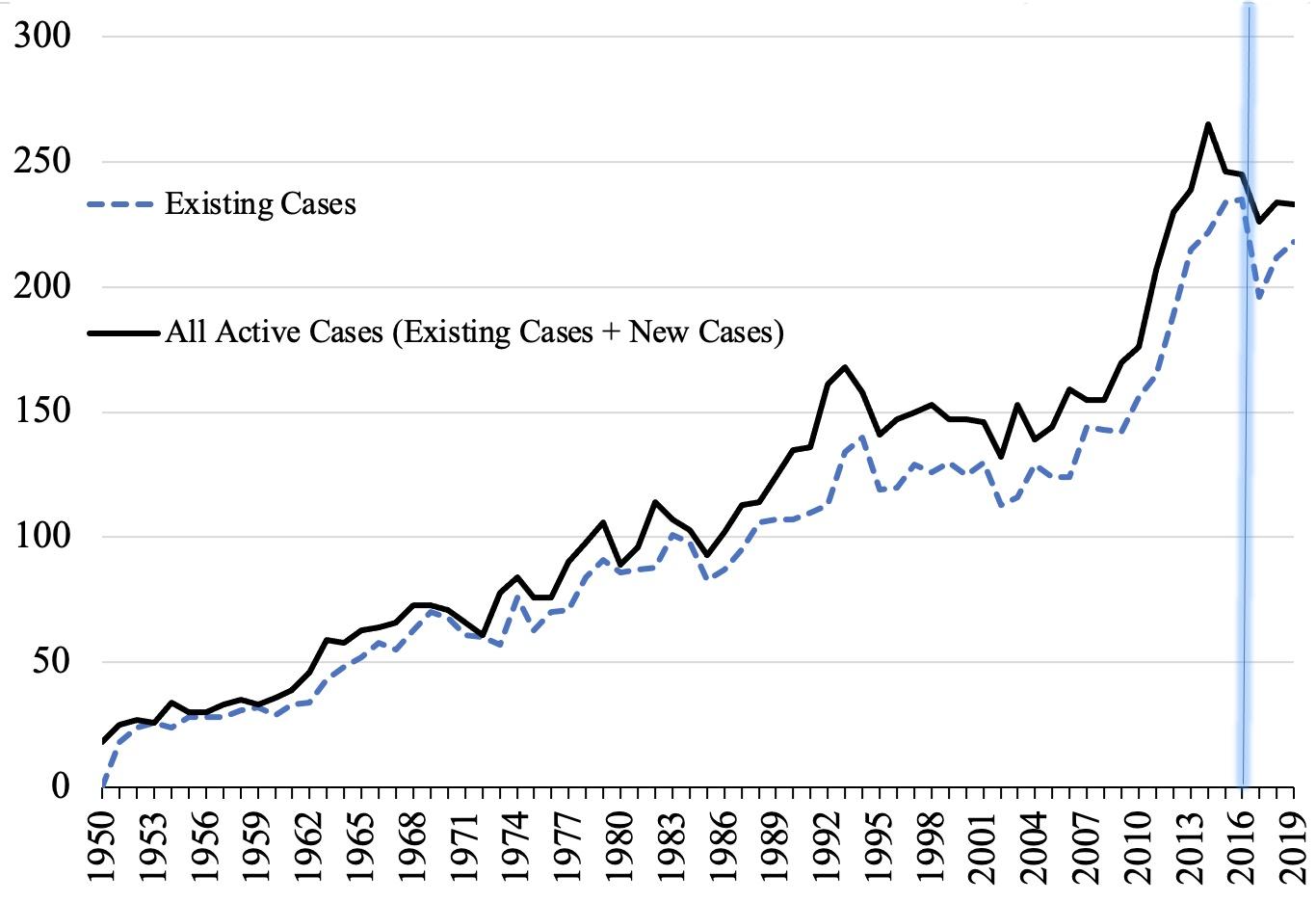

Figure 1 Evolution of Sanctions

a) Exisiting cases vs all active cases

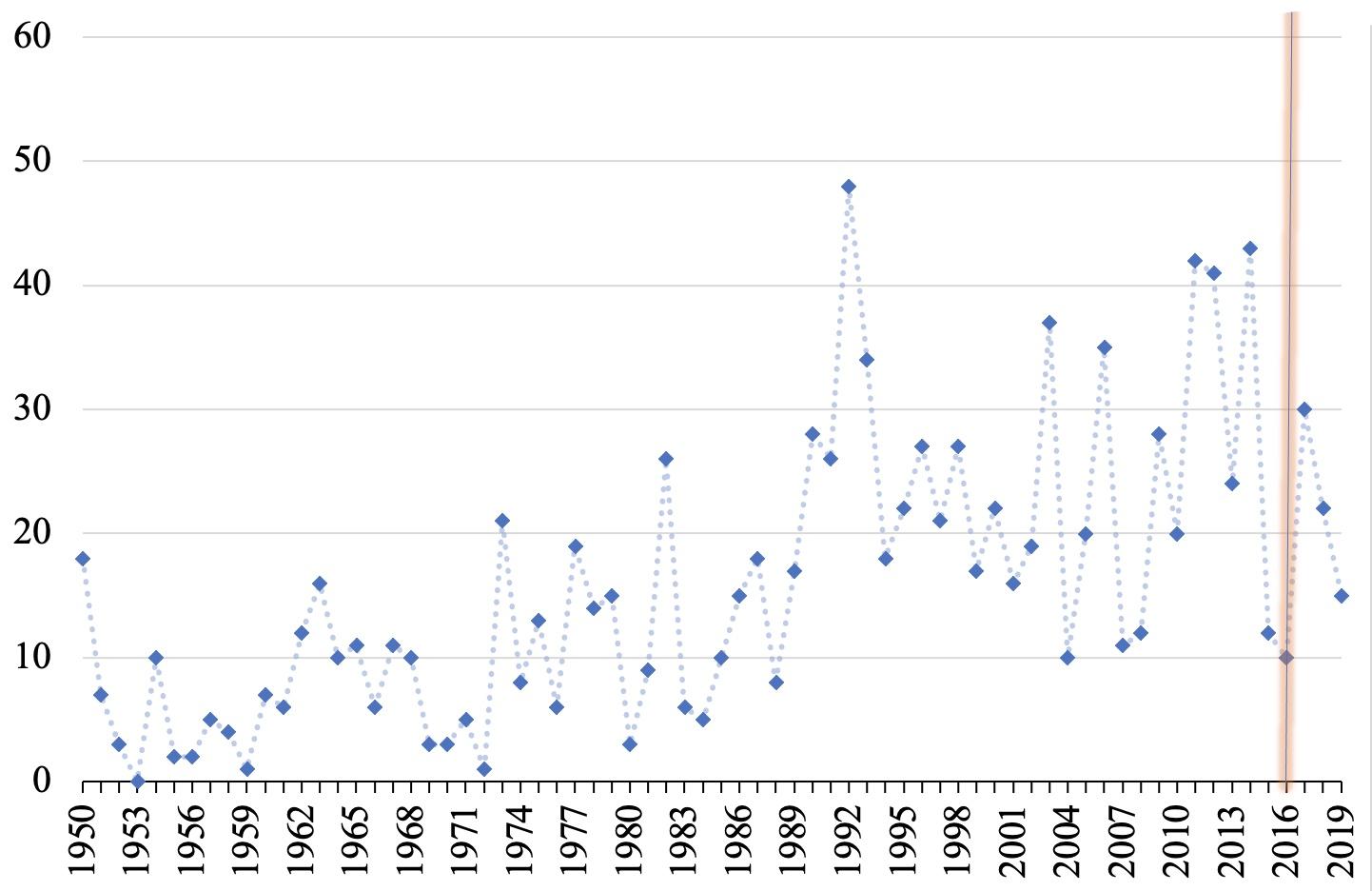

b) New cases

Note: This figure illustrates (a) the evolution of sanctions and (b) the yearly number of new sanctions impositions over the period 1950-2019.

Panel (a) of Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of all identified sanctions between 1950 and 2019. For each year over this period, the total number of imposed sanctions for the different types of sanctions is identified. Panel (b) of Figure 1 depicts the number of new sanction cases in each year for the period 1950-2019. Two important developments can be observed. First, the number of new sanction cases has, on average, increased over the period under consideration. Second, while the number of new sanction impositions turns out to be volatile in the 2000s, their number has, on average, increased. This development can be explained primarily by the more frequent adoption of so-called ‘smart sanctions’ (i.e. sanctions that typically target specific individuals, companies, or organisations with financial and/or travel restrictions).

The US as a major driver of international sanctions

The updated database allows for a detailed analysis of various policy and research questions. In what follows we briefly illustrate some new insights for the extended period. Our consideration of the 2016-2019 period is motivated by two ideas. First, because the original edition of the version of the database included sanctions up to the year 2016, all cases recorded during 2016-2019 constitute new additions and deserve some attention. The second idea is that these years coincided with most of Donald Trump’s term in office.

The focus on US sanctions can be explained by the following reasons. First, it is widely believed that the Trump administration imposed more sanctions than any other US administration. Second, according to the database, since 1950 the US has been the most frequent user of international sanctions in the world (accounting for more than one third of all observed sanction cases). Third, for various reasons, the US sanctions have been of keen interest to scholars working on sanctions research (e.g. Kohl 2021).

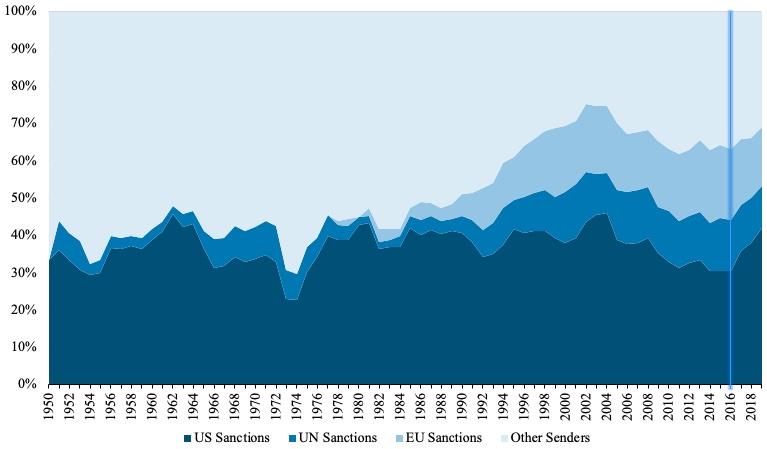

Figure 2 US vs. UN vs. EU Sanctions (% Worldwide)

Note: This figure depicts the yearly % of the sanctions imposed by the US vs. the % of sanctions imposed by the UN, the EU, and the rest of the world. The US has been the most frequent imposer of unilateral sanctions throughout 1950-2019. The percentage of the US sanctions increases during the Trump administration.

Figure 2 illustrates the dominant utilisation of sanctions by the US since 1950 to achieve its foreign policy objectives, as well as the increase in the frequency of their usage by the Trump administration. The US has been the single most frequent user of sanctions throughout this period. On average, more than 35% of all sanctions during 1950-2019 were imposed by the US. A noteworthy exception appears in the early 1970s.

Second, a significant and steady rise in the EU and UN sanctions is observed since the early 1990s. Finally, the Global Sanctions Data Base documents a strong difference between the evolution of the fraction of US sanctions under the Obama and the Trump administrations. Specifically, at the end of the Obama presidency in 2016, US sanctions accounted for 30% of all sanctions in the world. In contrast, in 2019 this fraction rose to more than 40% under the Trump administration.

Figure 3 Evolution of US Sanctions by Type, 1950-2019

a) US sanctions by type (number)

b) US sanctions by type (%)

Note: This figure illustrates the evolution of US sanctions by type. Panel (a) depicts the number of imposed sanctions by type in each year for the period 2005-2019, and panel (b) illustrates the percentage share of sanctions by type in each year for the same period. To facilitate readability the order of different sanction types in the legend corresponds to the order of the shaded areas in the two panels. There has been a significant increase in financial and travel sanctions during the years of the Trump presidency (2017-2019), followed by a decrease in the share of arms sanctions during these years.

Figure 3 depicts the types of sanctions employed by the US. In addition to confirming the increase in the absolute number of sanctions imposed by the Trump administration, two important patterns can be discerned from panel (a).

First, while trade sanctions appear to have risen significantly during the Obama years, there is a strong decline in 2017 due to the abolition of many active Obama sanctions in 2016. In contrast, arms sanctions remained relatively steady during the Trump years between 2016 and 2019, and military sanctions increased marginally.

Second, the Trump and Obama administrations differ in their imposition of smart (i.e. travel and financial) sanctions. Specifically, we observe a significant rise in the number of smart sanctions under Trump’s presidency. A possible explanation for this relative increase in the number of smart sanctions (which is consistent with a general worldwide trend) is that, by design, smart sanctions aim to influence policymakers in sanctioned countries by imposing economic pain on targeted individuals, companies, and/or economic sectors (in the hope of limiting the negative impact on ordinary people).

These stylised facts, which represent only a small fraction of possible additional insights that can be derived from the Global Sanctions Data Base, illustrate the increasing popularity of sanction policies. The update database offers a comprehensive collection of internationally observed sanction cases enabling researchers to analyse a large scope of important policy questions.

References

Crozet, M, J Hinz, A Stammann and J Wanner (2021), “Firms’ exporting behaviour to countries under sanctions”, VoxEU.org, 5 March.

Dizaji, S F and P A G van Bergeijk (2013), “Could Iranian sanctions work? ‘yes’ and ‘no’, but not ‘perhaps’”, VoxEU.org, 1 June.

Felbermayr, G, A Kirilakha, C Syropoulos, E Yalcin and Y V Yotov (2020a), “The Global Sanctions Database”, European Economic Review 129.

Felbermayr, G, A Kirilakha, C Syropoulos, E Yalcin and Y V Yotov (2020b), “The Global Sanctions Database”, VoxEU.org, 4 August.

GSDB (2021), “The Global Sanctions Data Base (GSDB)”.

Hufbauer, G C, J J Schott, K A Elliott and B Oegg (2007), Economic Sanctions Reconsidered (3rd edition), Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Kirilakha, A, G Felbermayr, C Syropoulos, E Yalcin and Y V Yotov (2021), "The Global Sanctions Data Base: An Update that Includes the Years of the Trump Presidency", in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.) Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar.

Kohl, T (2021), “In and Out of the Penalty Box: U.S. Sanctions and Their Effects on International Trade”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.) Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar.

Morgan, T C, N Bapat and Y Kobayashi (2014), “Threat and imposition of economic sanctions 1945-2005: Updating the TIES dataset”, Conflict Management and Peace Science 31 (5): 541-558.

Weber, P M and G Schneider (2020), “Post-Cold War sanctioning by the EU, the UN, and the US: Introducing the EUSANCT Dataset”, Conflict Management and Peace Science 20200827.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2012), “Failure and success of economic sanctions”, VoxEU.org, 27 March. Available at: https://voxeu.org/article/do-economic-sanctions-make-sense