Over the past three years, there has been a steady increase in international anti-trade rhetoric around the world, resulting in a real trade conflict between leading economies, including the US, China, and the EU (Bown 2017, Bown and Zhang, 2019)

The threat to free trade is, however, not new. Following the dramatic collapse of international trade in the wake of the financial crisis in 2007-8, there was a common fear that governments may respond to domestic economic challenges by increasing customs duties (tariffs) and other trade barriers to protect their economies. Such an uncoordinated restrictive trade policy might possibly have satisfied domestic interests in the short run as a symbolic reaction. At the same time, it would have resulted in an even stronger slowdown in economic growth.

Indeed, one big difference in how countries reacted to the global financial crisis of the 21st century in contrast to the great recession of the last century has been a stronger cooperation in international trade policies under the shelter of the WTO that has successfully prohibited a surge in border tariffs.

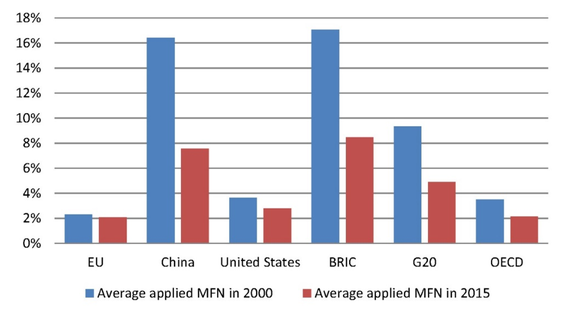

Figure 1 Average tariff developments across the world

Note: The figure presents average applied most favoured nation tariffs for the EU, China, the US, BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China), G20 countries and OECD member countries for the years 2000 and 2015.

Source: WITS Database.

Figure 1 illustrates the successful prohibition of tariffs across important countries and country groups. Average tariffs in all considered countries and regions have been declining. The extent of average tariff cuts varies across regions, partly due to the large differences in the level of customs duties in 2000. Advanced economies tend to have significantly lower average tariffs than emerging countries. These figures support the conclusion that the WTO successfully managed to maintain a trade liberalization process after the latest financial crises in 2009 and thereby supported the recovery of the world economy.

The new face of trade protectionism in the 21st century

The above assessment of global trade protection neglects other important trade policy instruments that have been increasingly used to protect domestic markets from international competition. In our latest empirical analysis (Kinzius et al. 2019), we illustrate the increasing relevance of so-called non-tariff barriers (NTBs) based on the Global Trade Alert database (Evenett and Fritz 2018) covering the years 2009 to 2014. NTBs are not clearly defined and incorporate a variety of measures, including import controls, state aid and subsidies, as well as public procurement and localisation policies. Unlike tariffs, which are transparent and accessible via each countries’ customs authority, NTBs are often much more hidden and therefore hard to assess.

The GTA database offers a systematic identification and provision of NTBs for a large number of countries. The database collects protectionist policies that were implemented worldwide since 2009. It covers an outstanding range of NTBs, which makes a detailed and up-to-date assessment of implemented NTBs possible.

Figure 2 Number of newly implemented protectionist interventions by type, 2009 - 2017

Note: Numbers in the bars represent a rise in protection by specific policies: we count the change in tariff increases (tariff changes), newly introduced anti-dumping, anti-subsidy and safeguard measures (trade defense), and newly introduced non-tariff barriers (non-tariff barriers) e.g. new national regulations.

Source: GTA.

Figure 2 illustrates that over the past years tariffs were not the major trade policy tool to protect domestic economies. Instead, NTBs have been most often applied. Since 2009, only 20% of all implemented protectionist interventions could be attributed to an increase in tariffs. In contrast, NTBs accounted for on average 55% of the implemented protectionist interventions. The use of NTBs increased steadily relative to trade defence measures which are normally used for a restricted time, for example in the form of anti-dumping duties. Moreover, while in 2010 54% of all protectionist interventions were NTBs, their usage increased to 61% in 2016. Trade defence measures observed a slight backdrop. In 2009, 30% of all applied protectionist policies could still be attributed to either anti-dumping duties, safeguards or countervailing duties. These measures dropped to only 21% in 2015, while increasing slightly again in 2016 – potentially driven by the increasing amount of anti-dumping disputes in industries with over-capacities like the steel sector.

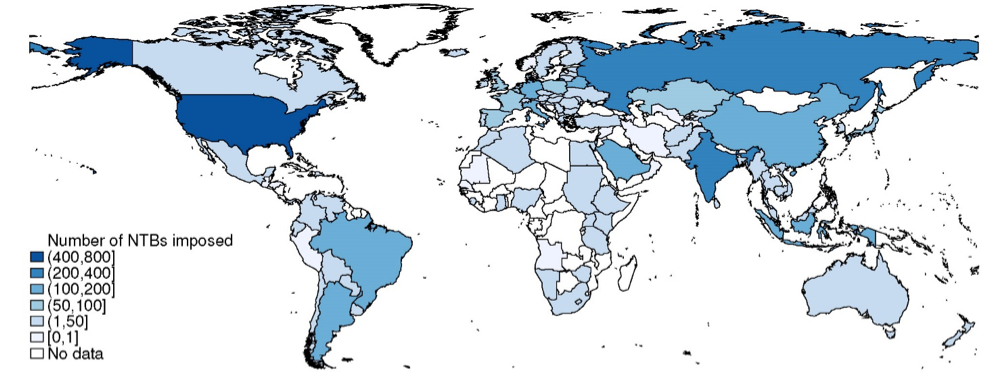

Figure 3 Number of NTBs imposed by country, 2009-2017

Note: Own calculations.

Source: GTA.

Figure 3 visualises the usage of NTBs across the world, pointing towards industrial and emerging economies as the main users of NTBs. Overall, the above numbers illustrate the increasing utilization of NTBs as trade policy instruments over the past years across the world. However, it remains unclear in how far such new measure influence international trade.

Quantification of NTB effects on trade

We estimate a structural gravity equation with tariffs pooled across different products based on Yotov et al. (2016). To identify the effect of NTBs on trade, we exploit the fact that for each implemented protectionist measure the GTA database has information about the detailed type of policy measure, trading partners that are most likely affected, products that are affected (at the CPC product level) and the year of implementation. We use this information to construct dummies for different types of protectionist policies. In the following, we present our three main specifications. The results are illustrated graphically in Figure 4.

In the baseline specification, we distinguish two groups of protectionist policies: trade defence measures and NTBs (Panel A of Figure 4). Imports decrease on average by 11.8% following the implementation of at least one NTB. This effect is significant at the 1% level. TDIs have a similarly large effect on bilateral trade flows. On average, imports of a particular product from a targeted country fall by 7.6% if at least one TDI is implemented against this product. The coefficients are significantly different from each other (5%), indicating that NTBs have on average a larger trade dampening effect than traditional TDIs.

It is reasonable to assume that NTBs have a smaller impact on imports from countries that have an FTA with the importer. For example, common sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS) of two countries that have an FTA would mean that such NTBs only affect countries outside the FTA. To investigate whether common FTA membership reduces the trade dampening effect of NTBs, the NTB dummy is interacted with a dummy identifying common FTA membership of the importer and the exporter.

The results of the second specification are illustrated in Panel B of Figure 4. The NTB coefficient identifies the effect of NTBs on imports from non-FTA exporters while the coefficient of the interaction term NTBxFTA identifies the difference in the trade effect of NTBs between non-FTA and FTA members. It is positive and statistically significant, indicating that imports from FTA members fall by less following an implementation of an NTB than imports from non-FTA countries

Figure 4 Gravity estimation results using OLS dummies of NTBs

Note: All regressions include exporter–importer-product, importer-product-time, exporter-product-time and exporter–importer-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at exporter–importer-product level. Tariff rates are controlled for but not reported. Variables for NTBs, TDIs and tariffs are lagged by 1 year. Except for tariffs all explanatory variables enter the regression as dummies. Estimates are transformed so that the y-axis shows the percentage change in bilateral trade in a particular sector following the imposition of at least one TDI / NTB. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Source: Kinzius et al. (2019).

In the third specification, we split NTBs into four subgroups: (1) import controls; (2) state aid and subsidy measures; (3) public procurement and localisation requirements; and (4) other NTBs, which include SPS, technical barriers to trade (TBT) and capital controls. As illustrated in Panel C of Figure 4, estimated coefficients are significantly negative for all four types of NTBs.

Beyond the above results, we also find that an individual NTB does not reduce trade as much as a traditional TDI. However, taking into account the number of implemented NTBs, their effect on trade is comparable to that of traditional TDIs such as anti-dumping, countervailing duties or safeguards. Import controls significantly reduce imports across all specifications. Specifically, the implementation of one additional import control reduces trade by 2–8%, so that imports fall on average by 2–11% if at least one import control is implemented. Public procurement and localization policies have an even larger average effect (8–16%), although evidence is less robust when it comes to marginal effects of one additional such policy. State aid and subsidies as well as other NTBs (SPS, TBT and capital controls) also reduce imports by up to 6 and 17% respectively.

Conclusion

Overall, the empirical analysis demonstrates the importance of exploiting new data on NTBs to reveal the significant protectionist impact of non-standard trade policies. For the period from 2009 to 2014, our baseline results show that implementation of at least one NTBs by a country reduce imports of affected products from targeted exporters by 4–12%, depending on the estimation method used. This negative effect can, however, be mitigated through FTAs. The results imply that the WTO should follow recent developments in bilateral trade agreements by accounting for NTB rules. More precisely, it should shift its focus towards multilateral agreements that aim at limiting the use of NTBs to avoid the increase in hidden protectionism that might otherwise result in lower levels of trade.

References

Bown, C (2017), “New eBook: Economics and policy in the Age of Trump,” VoxEU.org, 5 June.

Bown, C and E Zhang (2019), “Will a US-China trade deal remove or just restructure the massive 2018 tariffs?” VoxEU.org, 1 May.

Evenett, S and J Fritz (2018), Brazen Unilateralism: The US-China Tariff War in Perspective, the 23rd Global Trade Alert report.

Kinzius, L, A Sandkamp and E Yalcin (2019), “Trade protection and the role of non-tariff barriers,” Review of World Economics, forthcoming.

Yotov, Y V, R Piermartini, J-A Monteiro and M Larch (2016), An advanced guide to trade policy analysis: The structural gravity model, WTO.