A key feature of both socialism with Chinese characteristics and the Vietnamese socialist-oriented market economy has been the important contribution of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to these countries’ economies (Malesky and London 2014). Building off this pattern, the staggering success of these economies over the past three decades has triggered a new debate over ‘state capitalism’ as a viable growth and development model (The Economist 2012). Donald Trump recently heralded Vietnam as a role model for North Korean development. China’s growth, an even more striking success story, has competing explanations: the triumph of ‘markets over Mao’ and ‘state capitalism’, driven by large and successful SOEs (Lardy 2014, Hsieh and Song 2016). Our understanding of these new varieties of capitalism (or socialism) and of the new form of enterprises driving them is still very limited. What role do SOEs actually play in the economy? How do they respond, if at all, to market forces and reforms? Are they an obstacle or an engine of growth in a globalised economy?

In a recent paper (Baccini et al. 2019), we attempt to tackle this problem by studying the effect of the 2007 WTO accession on Vietnamese firms’ productivity, profitability, and survival rates. Our main findings suggest the presence of substantial selection effects for privately owned enterprises (POEs), with WTO entry reducing their average profitability and survival rate and increasing their average productivity. Nevertheless, we do not observe any of these effects for SOEs. A counterfactual exercise suggests that the productivity gains from trade five years after WTO entry would have been 66% higher if SOEs were replaced by private firms. Moreover, we show that the divergent pathways for SOEs and POEs after trade integration can be partially attributed to formal and informal benefits that advantaged SOEs, such as easier access to credit and regulatory barriers to business entry in certain sectors.

State-owned enterprises in Vietnam

Since the initiation of the Doi Moi in 1986, Vietnam had moved a substantial distance from its days of strict central planning. The state removed itself from a wide range of distortionary activities, market prices prevailed, and a large number of SOEs were been merged together, dissolved, or sold off. Most importantly, the reformed SOEs were expected to set their own prices based on market costs and were allowed to retain their profits and reinvest as they saw fit.1 Although Vietnam sought to reduce the number of SOEs, it simultaneously entrenched them by merging SOEs into large, Chaebol-like conglomerates and limiting entry into strategic sectors where SOEs operated. There were important development motivations behind this choice. The Vietnamese government relied on SOEs as a source of tax revenue and as a vehicle for economic redistribution to poor regions. Despite these noble goals, higher barriers to entry allowed SOEs to operate in less competitive markets where they were protected from domestic and foreign competition.

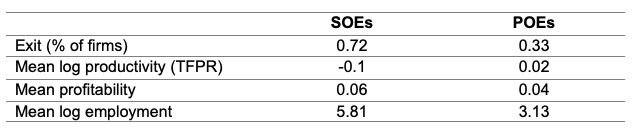

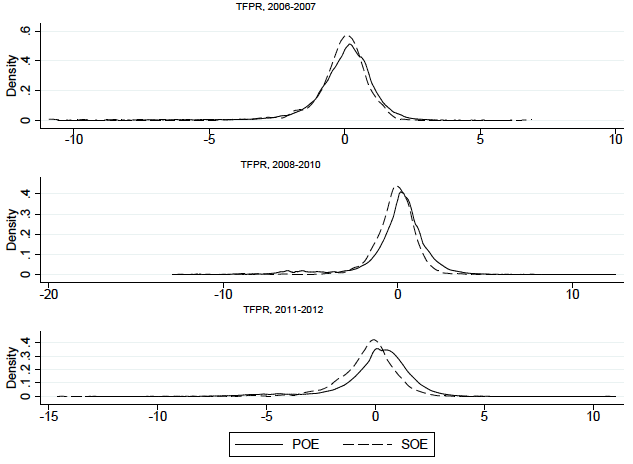

On the eve of WTO accession, the remaining SOEs accounted for less than 10% of total Vietnamese firms, but were present in all sectors of the economy and contributed a large share of capital (e.g. 80% in agriculture and electricity, 40% in manufacturing). Despite being corporatised and drastically reformed, on the eve of WTO access Vietnamese SOEs were more profitable and less productive than POEs, as shown in Table 1. Importantly, the productivity differences between SOEs and POEs expanded substantially after WTO entry. As can be seen in Figure 1, during the 2006-2007 period there was a wide productivity dispersion and a substantial overlap between the productivity distributions for the two types of firms. In the post-WTO years, however, the productivity distribution of POEs progressively shifted to the right, leading to a much larger gap between POEs and SOEs.

Table 1 Firms descriptive statistics before WTO accession (2006-2007)

Figure 1 SOE and POE productivity distribution before and after WTO accession

WTO entry: Competition, selection, and productivity

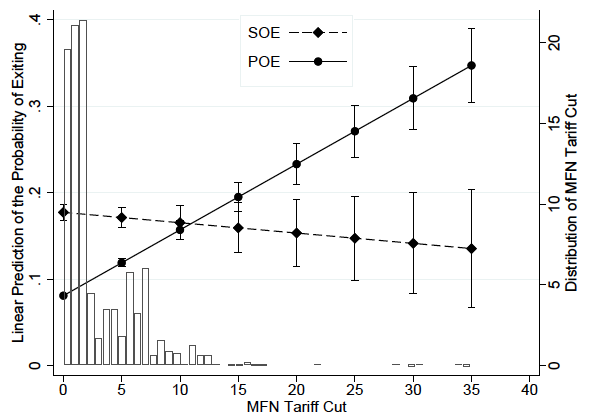

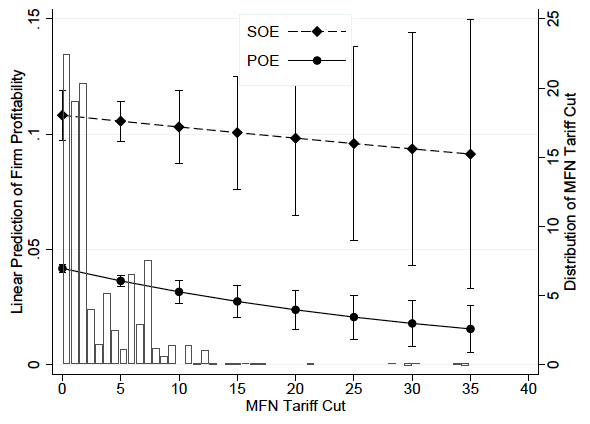

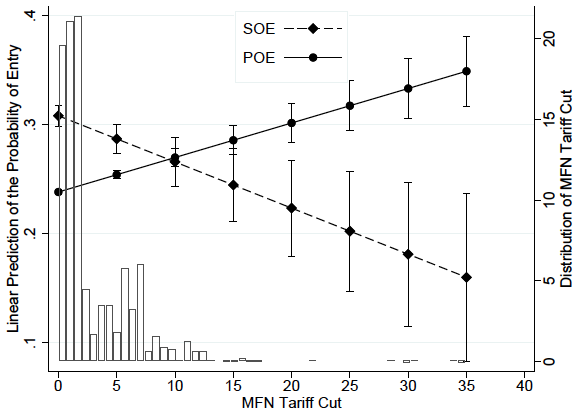

Because Vietnam was in a weak bargaining position in seeking accession to the WTO, most-favoured nation (MFN) tariff cuts provide arguably exogenous variation in international exposure, as tariff rates fell from an average of 20% in 2006 to 8% in 2009 and varied extensively across industries. Our econometric analysis, based on firm-level data from manufacturing firms in the Vietnam’s Enterprise Census, produces several fascinating findings. As predicted by canonical trade models (e.g. Melitz and Ottaviano 2008), firms’ profitability declined and poorly performing firms were driven out of the market. However, this trade-induced selection only applied to private companies. Figure 2 shows that in industries where the WTO accession brought stronger import tariff cuts, the survival probability of POEs experienced a stronger decline. Similarly, POEs’ profitability declines are associated with tariff cuts. Thus, the profitability decline is most pronounced in the industrial sectors that experienced the deepest cuts. By sharp contrast, there is no observable relationship between tariff cuts, profitability and survival among SOEs.

Figure 2 Effects of MFN tariff cuts on firms’ probability of exiting (top panel) and profitability (bottom panel)

By clearing the market of unproductive private firms, the trade-induced selection brought about by WTO entry increased manufacturing productivity by 3.7% annually in the five years following accession. Yet, no similar productivity improvement is evident among SOEs. The lack of structural adjustment by SOEs dampened the overall effects of integration. In fact, when we estimate the expected productivity increases of WTO entry if SOEs were removed from the economy, we find that annual gains in productivity would have been 40% higher!

Exploring the mechanisms: SOEs and behind-the-border barriers

Trade agreements have recently begun to involve discussions about behind-the-border barriers. These include domestic regulations on the environment, health, safety and labour standards, and domestic taxation, which often generate non-tariff barriers behind national borders. The WTO is taking its first steps in the direction of eliciting cooperation on this type of barriers (Ederington and Ruta, 2016). The empirical and theoretical literature are also trying to understand the nature of these barriers and the mechanisms through which they affect the outcomes of trade agreements (Brou and Ruta 2013, Antras and Steiger 2012, Costinot 2008). Drawing on Melitz and Ottaviano (2008) and Manova (2013) we build a theoretical model to explore the hypothesis that political/regulatory entry barriers and preferential access to credit can function as de facto behind-the-border barriers and hamper gains from ‘shallow’ integration limited to tariff reduction. The model delivers three predictions:

- Barriers to entry I. POEs facing high entry barriers due to credit constraints, therefore operating in less competitive markets, experience stronger competition and selection effects of trade.

- Barriers to entry II. Pecuniary barriers to entry cannot explain the different response of SOEs and POEs to trade, but political barriers to entry can.

- Barriers to exit. The neutrality of trade liberalisation for SOEs’ profitability and survival is produced by a bailout mechanism via credit supply.

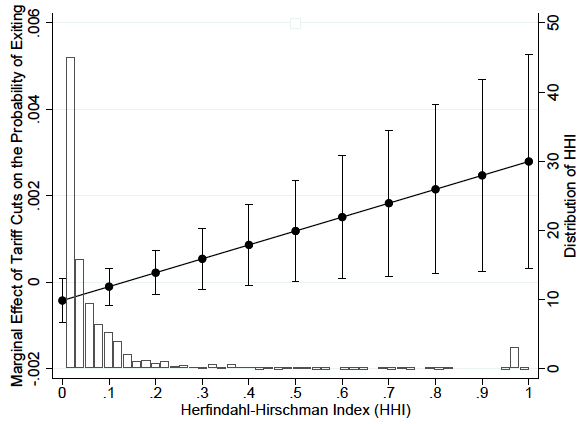

The top panel of Figure 3 shows evidence broadly supporting the model’s predictions. Sectors with higher market concentration (measured by a high Herfindahl index) feature a stronger effect of tariff cuts on the exit probability of POEs, while there is no significant effect for SOEs. Intuitively, higher entry barriers (perhaps due to greater credit constraints) generate more concentration. More concentrated, less competitive sectors benefit more from trade liberalisation, experiencing stronger competition and selection effects. SOEs tend to operate in sectors that are on average less competitive. The lack of competition in SOE-dominated sectors is less likely to be related to credit constraints and more likely to come from political barriers. If entry is politically controlled, it should not respond to trade liberalisation. Accordingly, the bottom panel of Figure 3 shows that firms’ entry increases with WTO tariff cuts for POEs but decreases for SOEs.

Figure 3 Selection effect and the role of barriers to entry and exit

Figure 4 Trade, selection, and firms’ credit

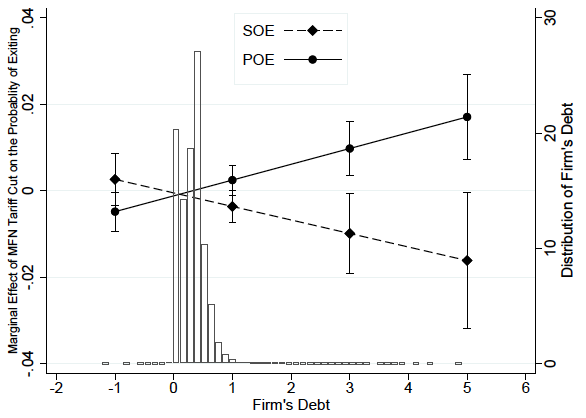

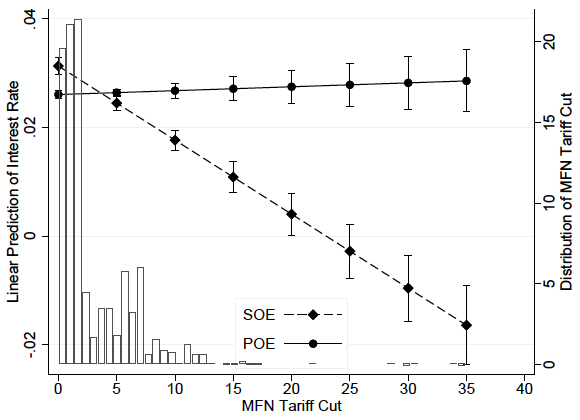

Finally, the top panel of Figure 4 shows that a given level of debt ratio (debt to own capital) increases the post-liberalisation probability of exiting for POEs but not for SOEs. This suggests that a given level of borrowing makes it harder for POEs to survive trade liberalisation, but it has no effect on SOEs’ exit rates. The model suggests that this differential behaviour is due to different borrowing costs faced by POEs and SOEs. To provide further support, we then ask whether trade openness affects the cost of credit differentially for POEs and SOEs (Figure 4, bottom panel). We find that the interest rate paid on their debt increases with trade liberalisation for POEs, and actually decreases for SOEs. This suggests that government might have helped SOEs face the trade-induced competition shock by reducing the cost of borrowing. This result is broadly compatible with the role of credit constraints as ‘de facto’ subsidies directly affecting the exit margin.

Concluding remarks

The idea that state capitalism can constitute a new model of development is fascinating and represents an important challenge for academics and policymakers. SOEs have the size to exploit economies of scale, the access to credit and government contracts to guarantee economic stability in turbulent times, but the risk of cronyism might outweigh the benefits. Our analysis shows that Vietnamese SOEs have hampered the efficiency gains brought about by globalisation. Their ‘political advantage’ creates serious obstacles to the structural adjustments needed for a country to fully reap the benefits of trade integration.

References

Antràs, P and R W Staiger (2012), “Offshoring and the role of trade agreements”, American Economic Review 102(7): 3140-83.

Baccini, L, G Impullitti and E J Malesky, (2019), “Globalization and state capitalism”, Journal of International Economics, forthcoming.

Brou, D and M Ruta (2013), “A commitment theory of subsidy agreements”, The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 13(1): 239-270.

Costinot, A (2008), “A comparative institutional analysis of agreements on product standards”, Journal of International Economics 75(1): 197-213.

The Economist (2012), “Emerging Market Multinationals: The Rise of State Capitalism", 21 January.

Ederington, J and M Ruta (2016), “Nontariff measures and the world trading system”, Handbook of Commercial Policy 1: 211-277.

Hsie, C-T and Z Song (2015), “Grasp the Large, Let Go of the Small: The Transformation of the State Sector in China”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring.

Lardy, N (2014), Markets over Mao, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Malesky, E and J London (2014), “The political economy of development in China and Vietnam”, Annual Review of Political Science 17: 395-419.

Manova, K (2013), “Credit Constraints, Heterogeneous Firms, and International Trade”, Review of Economic Studies 80: 711-744.

Melitz, M J and G I Ottaviano (2008), “Market Size, Trade, and Productivity”, The Review of Economic Studies 75(1): 295-316.

Endnotes

[1] A similar reform process took place in China in the 1990s, in which SOEs were ‘corporatised’ and merged into large state-owned conglomerates; see Hsieh and Song (2015) for details.