Recent decades have seen a proliferation of regional trade agreements. There are currently more than 300 of these agreements in force, most of which take the form of free trade agreements (FTAs). For example, the US has 14 FTAs in force with 20 countries, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS). Multilateral rules require members of regional trade agreements to reciprocally eliminate “duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce” on “substantially all the trade” between them.1

According to Rodrik (2018), FTAs “are shaped largely by rent-seeking, self-interested behavior on the export side. Rather than rein in protectionists, they empower another set of special interests and politically well-connected firms, such as international banks, pharmaceutical companies, and multinational corporations.”

Rodrik’s argument seems in contrast with the standard view that trade liberalisation is opposed by import-competing interests, who lobby in favour of protection. This standard view is elegantly captured in the ‘Protection for Sale’ model by Grossman and Helpman (1994) and has been supported by several studies (e.g. Goldberg and Maggi 1999, Gawande and Bandyopadhyay 2000, Bombardini 2008). It should be stressed, however, that this literature is focused on unilateral and sector-specific trade policies, so domestic firms have nothing to gain from trade liberalisation. By contrast, FTAs are reciprocal – allowing exporting firms to improve access to foreign markets for their final goods – and cover multiple sectors, thus reducing the cost of importing intermediate inputs.

Firm-level lobbying on trade agreements

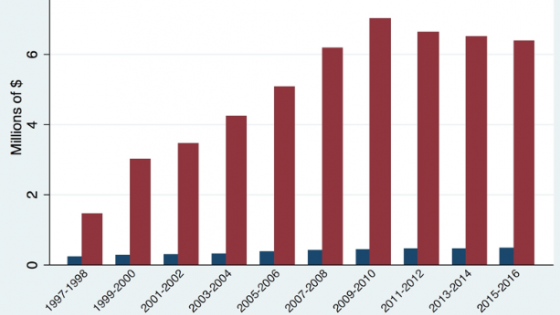

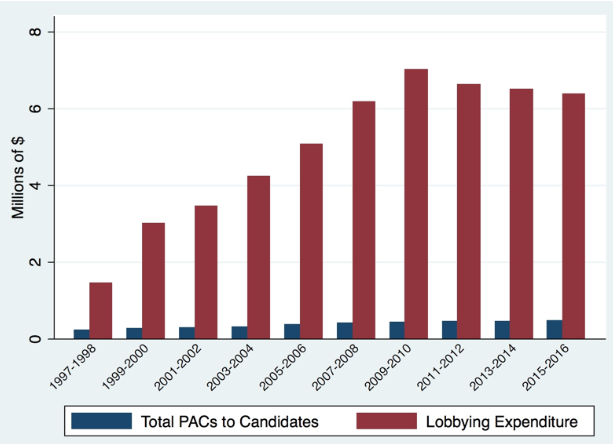

In a recent paper (Blanga-Gubbay et al. 2020a), we study theoretically and empirically how firms shape the political economy of trade agreements. We start by looking at the data, exploiting detailed information from lobbying reports available under the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995. This Act requires individuals and organisations to file semi-annual reports providing information on their lobbying activities at the federal level and imposes significant civil and criminal penalties for violations of its requirements. All lobbying expenditures must be disclosed, no matter how small. Data on lobbying reports have been used in recent studies on lobbying (e.g. Blanes i Vidal et al. 2012, Bertrand et al. 2014, Kim 2017). Using these data has two key advantages compared to the data on campaign contributions that were used in earlier studies. First, data on lobbying expenditures can directly be traced to the issues targeted by lobbyists, which is not possible for data on contributions. This is because the Lobbying Disclosure Act requires the disclosure of not only the amounts of lobbying expenditures, but also the issues for which the lobbying is carried out. Second, lobbying expenditures are the most important channel of political influence, more than ten times larger than Political Action Committee (PAC) contributions (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 Lobbying expenditures vs campaign contributions (all issues)

Notes: The figure reports the total amounts of lobbying expenditures and campaign contributions on all policy issues, between the 105th Congress (1997-1998) and the 114th Congress (2015-2016). The data come from the Center for Responsive Politics.

We collect all reports filed by firms related to lobbying expenditures on FTAs negotiated by the US.2 Our dataset provides information on the identity of the lobbying firm, its lobbying expenditure on a particular FTA, and whether it supported or opposed the agreement.

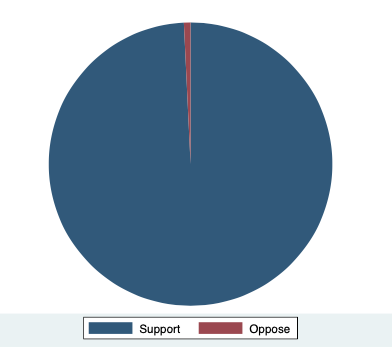

Using this dataset, we uncover new facts about firm-level lobbying on trade agreements. The most striking of these facts is that virtually all firms that lobby on FTAs support their ratification. In 99.25% of the cases, lobbying firms are in favour of the trade agreements (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2 Firms’ position on US FTAs

We also find that relative to non-lobbying firms, firms that lobby on FTAs are larger, more likely to be engaged in international trade, and tend to operate in sectors in which the US has a comparative advantage.

Selection into lobbying by the largest winners

These novel facts cannot be explained by the existing literature on the political economy of FTAs, which is focused on industries rather than firms.3 We thus develop a new model of the political economy of trade agreements with heterogeneous firms.

We consider first the distributional effects of an FTA in the canonical model of firm heterogeneity under monopolistic competition (Melitz 2003). By eliminating all tariffs among members, the entry into force of an FTA creates winners and losers. Non-exporting firms lose since they suffer from the increase in competition in the domestic market and do not benefit from improved access to the foreign market. By contrast, exporting firms gain, with the most productive among them being the largest winners. Crucially, these ‘superstar’ firms have higher stakes in the agreement than the biggest losers. Their gains are larger in absolute terms than the maximum losses incurred by non-exporting firms.

In a monopolistically competitive setting, each individual firm has no mass and thus no impact on market and policy outcomes. We show that the key insights of Melitz (2003) about the distributional effects of an FTA can be extended to models with heterogeneous oligopolistic firms, if the presence of a competitive fringe or comparative advantage shelter large exporting firms from losses in their domestic market.

The political structure of the model is characterised by two key features. First, in line with what we observe in the data, lobbying expenditures are paid before the policy outcome is realised. To model ex-ante lobbying, we follow the literature on lobbying/rent-seeking in contests (e.g. Tullock 1980, Dixit 1987, Siegel 2010). Firms choose whether to be politically organised and how much to lobby in favour of or against a proposed FTA, anticipating the impact of their lobbying expenditures on the probability of ratification. Second, politicians deciding on the ratification of the FTA may be biased in favour of or against it, and there is some uncertainty about this political bias. This feature captures the political uncertainty faced by firms when making their lobbying decisions.

The model provides a simple explanation for why lobbying firms are always in favour of FTAs: only firms with the largest stakes in a policy are politically organised. Since the biggest winners from a trade agreement have higher stakes than the biggest losers, only the largest pro-FTA firms select into lobbying. The model is also consistent with the other facts that emerge from our dataset. It can explain why lobbying firms are larger, more likely to be engaged in international trade, and to operate in comparative advantage sectors than non-lobbying firms.

The intensive margin of lobbying

We derive testable predictions about the determinants of expenditures by lobbying firms. First, larger firms should spend more lobbying in support of trade agreements. Second, individual firms should spend more when their potential gains from the improved access to the foreign market are larger. Third, lobbying expenditures should increase in the probability that legislators are biased against ratifying the agreement. Intuitively, when politicians are more likely to be in favour of the agreement, pro-FTA firms can free ride on their preferences and exert less effort.

To assess the validity of these predictions, we exploit both cross-firm and within-firm variation in lobbying expenditures on trade agreements. In line with the first prediction, we find that larger firms spend more in favour of the ratification of FTAs. We also find strong empirical support for the second prediction: individual firms spend more supporting FTAs when their potential gains from the agreement are larger. These potential gains are captured in terms of (i) the extent of the reduction in the tariffs they face to export their final goods and to import their intermediate inputs, (ii) the depth of the agreement, and (iii) the export and sourcing potential of the FTA partners. Finally, individual firms spend more in support of FTAs when US congressmen are less likely to be in favour of ratification.

Concluding remarks

Overall, our analysis shows that lobbying on FTAs has been dominated by a few very large firms, which experience large gains as a result of the entry into force of these agreements. By contrast, losing firms have had no voice in the lobbying process, finding it too costly to be politically organised.

An important avenue of future research is to understand the extent to which firms shape the content of trade agreements. In an ongoing separate project, we examine whether firms can influence provisions on non-trade issues, e.g. rules on intellectual property rights and investment (Blanga-Gubbay et al. 2020b).4

References

Bertrand, M, M Bombardini and F Trebbi (2014), “Is It Whom You Know or What You Know? An Empirical Assessment of the Lobbying Process”, American Economic Review 104: 3885-3920.

Blanes i Vidal, J, M Draca and C Fons-Rosen (2012), “Revolving Door Lobbyists”, American Economic Review 102: 3731-3748.

Blanga-Gubbay, M, P Conconi and M Parenti (2020a), “Globalization for Sale”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14597.

Blanga-Gubbay, M, P Conconi, I S Kim and M Parenti (2020b), “Lobbying by Firms on Deep Trade Agreements”, mimeo.

Bombardini, M (2008), “Firm Heterogeneity and Lobby Participation”, Journal of International Economics 75: 329-348.

Dixit, A K (1987), “Strategic Behavior in Contests”, American Economic Review 77:891-898.

Gawande, K and U Bandyopadhyay (2000), “Is Protection for Sale? Evidence on the Grossman-Helpman Theory of Endogenous Protection”, Review of Economics and Statistics 82: 139-152.

Goldberg, P K and G Maggi (1999), “Protection for Sale: An Empirical Investigation”, American Economic Review 89: 1135-1155.

Grossman, G M and E Helpman (1994), “Protection for Sale”, American Economic Review 84: 833-850.

Grossman, G M and E Helpman (1995), “The Politics of Free Trade Agreements”, American Economic Review 85: 667-690.

Kim, I S (2017), “Political Cleavages within Industry: Firm-level Lobbying for Trade Liberalization”, American Political Science Review 111: 1-20.

Kohl, T, J Lake and S Hakobyan (2020), “Lobbying for Tariff Phase-Outs in United States Free Trade Agreements”, mimeo.

Melitz, M J (2003), “The Impact of Trade on Intra-industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity”, Econometrica 71: 1695-1725.

Rodrik, D (2018), “What Do Trade Agreements Really Do?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 23: 73-90.

Siegel, R (2010), “Asymmetric Contests with Conditional Investments”, American Economic Review 100: 2230-2260.

Tullock, G (1980), “Efficient Rent Seeking”, in J Buchanan, R Tollison and G Tullock (Eds.), Toward a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society, Texas A&M University Press.

Endnotes

1 In line with Article XXIV of the GATT/WTO, very few products are indeed excluded from FTA, as shown by Kohl et al. (2020). For example, the US did not exclude any HS8 good from the NAFTA agreement. The highest percentage of products excluded by the US is 1.73 (in the case of the FTA with Australia).

2 Our main dataset is based on all reports that explicitly mention the FTA ratification bills in Congress. Our results are robust to using keywords rather than bill numbers as an alternative methodology to trace lobbying reports related to a particular agreement.

3 The workhorse model in this literature is Grossman and Helpman (1995), which applies the ‘Protection for Sale’ framework to study lobbying by industry groups on a proposed FTA. In this model, lobbying is exogenous: it is simply assumed that some industries are organized, while others are not. Moreover, contributions are paid ex-post (i.e. after the incumbent government has decided whether or not to ratify the agreement), while actual lobbying expenditures are paid ex-ante (i.e. before the ratification of the agreement).

4 Anecdotal evidence suggests that large corporations are able to ‘buy’ favourable provisions in trade agreements. For example, in the first quarter of 2012, GlaxoSmithKline spent $2,120,000 lobbying on the ‘Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPP) - provisions related to intellectual property’, among other issues. Other pharmaceutical companies spent considerable amounts lobbying on this agreement. The text of the TPP agreement seems to reflect these lobbying efforts, since it contains various provisions that are particularly favourable to drug manufacturers (e.g. strengthening patent exclusivity, providing protections against bulk government purchasing).