Looking at the fate of the fifteen states that emerged from the Soviet Union, it is striking how different their economic evolutions have been. The severity of the plunge around 1989 was closely related to the extent of the systemic failure of central planning as well as to local mismanagement.

Estonia, after regaining independence in 1991, quickly embarked on bold and decisive political, institutional, and economic reforms. Strong, sustained growth followed. Within thirteen years Estonia could accede to the EU. The “EU perspective” provided a critical anchor for sustained reforms.

In contrast, Georgia, after regaining independence, was torn by civil war, caught in a low-income trap, and suffered from pervasive corruption. The country lacked bold economic and institutional reforms. The absence of a EU perspective and a tense relationship with Russia did not help. But the Rose Revolution in 2003 inspired hopes for fundamental reforms and economic advance. Indeed, in 2007, Georgia became “the number one economic reformer” (World Bank, 2007). Between 2006 and 2007, Georgia skyrocketed from 112th place to 18th by the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index. Georgia is now just one place behind Estonia.

The plunge in recorded output was significantly deeper and lasted longer in Georgia than in Estonia (Figure 1). In Georgia, GDP per capita contracted by almost 80% from 1988 to 1994 while in Estonia it fell by 33% (1989-93). Even so, since 1993, Estonia’s GDP per capita has grown more rapidly than that of Georgia – 6.6% annually compared to Georgia’s 6.1%.

Economic growth can be either extensive, driven by the build-up of capital, or intensive, springing from more efficient use of existing capital through the accumulation of live capital via education, on-the-job training, and health care. Free trade enables countries to break outside their production frontiers. Good institutions and good governance help generate sustained growth.

Figure 1 GDP per capita 1975-2005

Note: Constant 2000 international dollars at purchasing power parity

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2007.

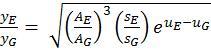

We have attempted a rudimentary quantitative assessment of the contributions of education, investment, and efficiency to the relative per capita incomes of Estonia and Georgia, employing a simple Cobb-Douglas constant-returns-to-scale production function that yields the equation1

Here y is GDP per capita, A is efficiency, s is the share of investment in GDP, and u is the number of years of schooling. The subscripts E and G represent Estonia and Georgia. The square root and the cube follow from the underlying Cobb-Douglas formulation.

Investment, trade, and education

To understand the income differential between Estonia and Georgia we need to estimate the relative contributions of investment, education, and efficiency.

We start with domestic investment. Estonia invested 29% of GDP in machinery and equipment on average 1989-2005 compared with 20% in Georgia. Foreign investment was virtually nonexistent in the early 1990s. Since then Estonia has attracted more foreign capital than Georgia. Net inflows of FDI in Estonia amounted to 7% of GDP 1992-2005 on average compared with 4% in Georgia. Estonia has also been more open than Georgia to foreign trade. Exports of goods and services from Estonia amounted to 73% of GDP on average 1992-2005 compared with 33% in Georgia. Geography helped, and so did a liberal trade policy outlook: When Estonia’s foreign markets collapsed in the 1990s, it managed quickly to win new markets for its exports. Georgia could not.

Turning to human capital, nearly all Estonian youngsters attend secondary schools compared with four-fifths of Georgians. In 2004, nearly two-thirds of young Estonians attended colleges and universities compared with 42% in Georgia. In recent years, public and private expenditure on education amounted to about 6% of GDP in Estonia compared with 2% in Georgia. Neither of these input measures captures the quality of education, however, a common problem in education research. With early reforms, Estonia sought harmonisation with EU standards, another benefit of the aforementioned EU perspective. Education reform in Georgia started more recently.

Other indicators point in the same direction. In Estonia, there were 483 personal computers per 1,000 inhabitants in 2005, almost the same figure as in Finland, compared with 42 personal computers in Georgia in 2004. Likewise, in Estonia, there were 513 internet users per 1,000 inhabitants in 2005, the same as in Finland in 2004; the Georgian figure for 2004 is 39 internet users per 1,000 inhabitants. Estonia now has more mobile phone subscribers than people, surpassing even Finland next door, while Georgia has 326 mobile phone subscribers per 1,000 inhabitants. Education and technological sophistication are clearly conducive to a business-friendly climate for domestic as well as foreign investment.

Democracy and governance

Due to the difficult status of its Russian citizens, Estonia does not score high in surveys of democracy. According to the Polity IV Project, Estonia only scores six out of ten. For comparison, Georgia has scored between four and five since 1992 and, more recently, in 2004, seven. Democracy is good for growth because it improves governance. Democratisation can be viewed as an investment in social capital.

According to the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, about the same proportion of managers surveyed in 2005 said they lacked confidence in the court system to uphold property rights (30% in Estonia, 29% in Georgia). In Estonia, two% of the managers surveyed described crime as a major business constraint compared with 24% in Georgia. Further, according to Transparency International, Estonia is less corrupt than Georgia. On a scale from one to ten, there is a three-to-four-point difference between the corruption perceptions indices for Estonia and Georgia. In 2005, 20% of managers surveyed in Georgia described corruption as a major constraint on their business operations compared with 4% of managers in Estonia. Since 1999, Estonia has made some progress in the battle against corruption. Georgia has not.

Accounting for the income differential

In 2005, Estonia’s per capita GDP was 4.73 times larger than that of Georgia. The average investment rates were 0.29 in Estonia and 0.20 in Georgia as mentioned before. The imputed years of schooling are 14.2 years in Estonia and 12.7 for Georgia. When we plug these numbers into our formula, we find that differences in education measured by years of schooling could by themselves explain a bit more than a twofold per-capita-output difference between Estonia and Georgia. Different investment rates could likewise explain a 20% income differential. This leaves an 86% per-capita-output difference between Estonia and Georgia to be explained by the efficiency differential, including differences in trade, inflation, economic structure, and various aspects of governance as we have discussed. Put differently, our computation suggests that education and efficiency make roughly comparable contributions to explaining the income differential between Estonia and Georgia, while investment plays a less significant role. Intensive growth is what counts.

Policy implications

Our comparison of the different development trajectories of Estonia and Georgia since 1991 suggests policy implications that seem especially relevant to Georgia and other second-tier former Soviet states, as well as other countries lagging behind their erstwhile equals. In brief, rapid economic growth requires:

- public policies that foster education and training, free trade, and domestic as well as foreign investment in a business-friendly environment;

- monetary and fiscal policies that support price stability and sound private banking and other financial intermediation, sustainable government budget positions, and international, consumer-friendly competition;

- sound and transparent societal institutions that support the rule of law; and

- good governance of both the public sector and the private sector.

Further, the prospect of EU membership may create favourable conditions for sound economic policies, rapid structural change, and institution building in relevant countries. Such a EU perspective may also help to forge a broad-based political consensus on the policy actions required for change.

We can summarise our findings as follows.

First, Estonia has invested significantly more relative to GDP than Georgia and also attracted more foreign investment than Georgia, thereby accumulating capital and increasing output per person.

Second, Estonia sends more young people to secondary schools and higher education than Georgia does, thereby building up precious human capital that, like real capital accumulation, helps lift output per person to higher levels and encourages long-term growth. Estonia’s strong emphasis on education at all levels is reinforced by its rapidly increasing technological sophistication as evidenced by widespread personal computer and mobile phone ownership.

Third, Estonia has done more than Georgia to increase economic efficiency – that is, total factor productivity. This effort has taken many different forms, including the important trinity of liberalisation, privatisation, and stabilisation. Estonia did

- increase its openness to trade in goods, services, and capital;

- privatise its banks and other erstwhile state enterprises while ensuring competition through, among other things, foreign ownership; and

- stabilise prices following the temporary bout of inflation that was bound to follow the rapid liberalisation of prices at the beginning of transition.

Estonia has moved farther and faster in a growth-friendly direction. Corruption and associated problems are much less of an issue in Estonia than in Georgia.

In view of all this, it is not surprising that Estonia has grown more rapidly than Georgia. The growth differential would have been significantly smaller had Georgia embarked earlier on fundamental reforms. The proportions in which the different factors we have discussed account for the growth differential between the two countries since 1991 remain to be quantified in detail. Even so, we think the qualitative point we have made is pretty clear. You judge.

References

Gylfason, T., and E. Hochreiter (2008), “Growing Apart? A Tale of Two Republics: Estonia and Georgia“, IMF Working Paper, forthcoming.

Hall, R. E., and C. I. Jones (1999), “Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker Than Others?,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 114, No. 1, February, 83-116.

World Bank (2007), Doing Business – Economy Rankings. Available at http://www.doingbusiness.org. See also http://www.enterprisesurveys.org.

1 For the derivation, see Gylfason and Hochreiter (2008). See also Hall and Jones (1999).