During the Great Recession, governments enacted fiscal stimulus packages to combat the decline in economic activity. Significant spending on long-lived investment goods was common to these policies. In the US, for instance, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 contained provisions to raise funding to spend more than $70 billion on infrastructure and transportation.1

In other countries infrastructure investment was also a significant fraction of stimulus spending, most notably China, where it made up approximately 40% (International Labour Organisation 2011). Debates on fiscal stimulus typically assume government investment is highly effective. For instance, Paul Krugman wrote in the New York Times (Krugman 2016):

“[T]he simplest, most effective answer to a downturn would be fiscal stimulus – preferably government spending on much-needed infrastructure.”

I have been studying the fiscal multiplier associated with government investment, and comparing it to the multiplier of government consumption spending (Boehm 2019). The fiscal multiplier measures by how many dollars GDP increases after a one dollar increase in expenditure.

I found that a large and conventional class of macroeconomic models predicts that the government investment multiplier for short-lived shocks (such as the stimulus during the Great Recession) is small – typically below 20 cents on the dollar. This contrasts with the government consumption multiplier, which is between 0.6 and 1 under standard assumptions on parameters.

So I estimated government consumption and investment multipliers in a panel of OECD countries. The data broadly support the theory's predictions: The estimated government consumption multiplier is around 0.8, and the government investment multiplier near zero.

Why could the government investment multiplier be small?

Standard macroeconomic models predict that the investment multiplier is small because private investment falls drastically after temporary government investment shocks – known as 'crowding out'. Intuitively, a transitory increase in government purchases raises the price of goods today relative to tomorrow. This prospect of falling prices leads households and firms to delay expenditures, offsetting the government increase in demand.

The degree to which purchases can be delayed is much higher for durable investment goods such as cars, manufacturing equipment, or structures, than for nondurable consumption goods such as groceries or haircuts (e.g. Mankiw 1985). As a result, a large class of models predicts that the government investment multiplier associated with transitory expenditure increases is smaller than the government consumption multiplier.

Evidence for a small government investment multiplier

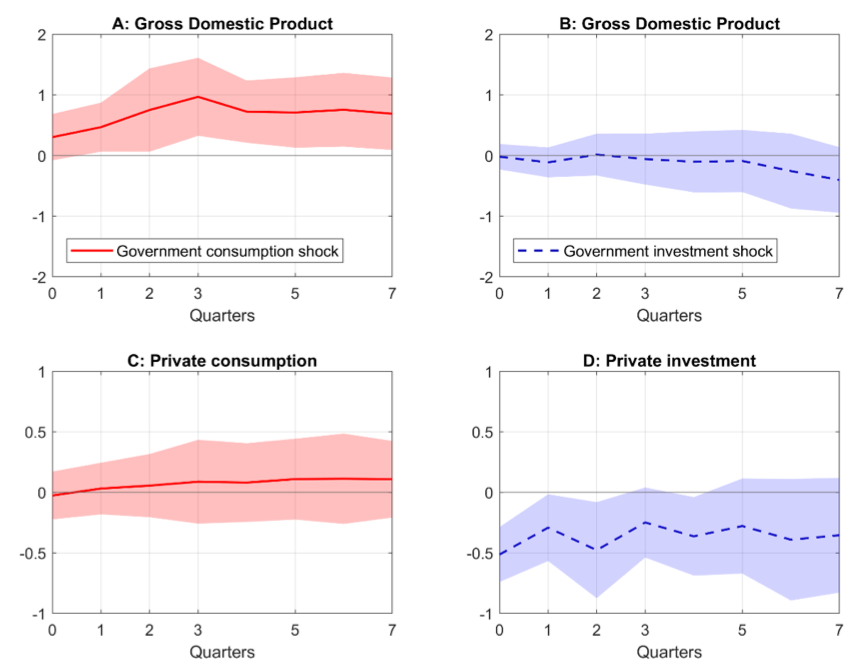

To estimate government consumption and investment multipliers, I build on prior work by Blanchard and Perotti (2002), Ramey (2011), and Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012). Figure 1 illustrates the estimated responses after a one-dollar increase in government expenditures.

Figure 1 Estimated GDP response to increase in government expenditure on consumption and investment, and crowding out

Source: Boehm (2019).

In response to a government consumption shock, GDP rises above zero and becomes statistically significant in the second quarter (Panel A). In contrast, GDP remains indistinguishable from zero at all horizons after a government investment shock (Panel B). The associated multipliers are approximately 0.8 for government consumption, and near zero for government investment.

Panel C demonstrates that private consumption remains roughly unchanged after a government consumption shock, suggesting that there is no offsetting drop in private demand. At no horizon is the response significantly different from zero at the 10% level. This contrasts with the behaviour of private investment shown in Panel D. After a government investment shock, private investment falls significantly below zero – without a lag. The estimates become insignificant in the sixth quarter, but remain more than one standard error below zero until the eighth quarter. Hence, the data support the theories’ prediction that private investment is crowded out, and the government investment multiplier small.

Recent work has argued that the government expenditure multiplier could be greater when the monetary authority is constrained by the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates (for example Christiano et al. 2011), or when factors of production are underutilised as is the case during downturns (Auerbach and Gorodnichenko 2012). When I tested these predictions separately for government consumption and investment, I found some evidence for larger multipliers at the zero lower bound. No robust differences emerge when I estimate separate multipliers for alternative states of the business cycle.

Multipliers that mislead

A small multiplier for temporary increases in government investment does not imply that government investment is undesirable. In fact, research has shown that government capital is productive (Aschauer 1989) and found that the government investment multiplier can be large in the long run (Baxter and King 1993). Since the productivity effects of government capital operate at much longer time horizons than the short-lived demand effects associated with fiscal stimulus programs, the alternative mechanisms are mutually consistent and evidence in favour of one should not be interpreted as evidence against the other.

And yet, my findings raise concerns about the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus targeted on infrastructure. As with many other stimulus programs, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act contained provisions to raise spending on highly durable goods such as highway infrastructure, high-speed rail corridors, railroads, airports, and broadband. This investment may be desirable for many reasons, but it is not clear that it stimulates aggregate demand. The data suggests that any increase in government demand is offset by shortfalls in private demand.

My work also has implications for the empirical research on fiscal policy. If different components of government expenditures are associated with different multipliers, the multiplier for total government purchases, which is commonly estimated, may have external validity problems. Building on earlier work by Kraay (2012), I could show that the multiplier for total purchases is approximately a weighted average of the government consumption and investment multipliers, in which the weights reflect the composition of purchases.

Since this composition generally differs across applications, the multiplier for total purchases can vary, even if the multipliers of government consumption and investment remain unchanged. For instance, if a stimulus program has a different composition of government consumption and investment to the identifying variation for the estimated multiplier, then this estimate will be a misleading guide for policymakers. Similarly, we would not expect that estimates for the multiplier of total purchases are necessarily comparable across samples and identification schemes.

References

Aschauer, D A (1989), “Is public expenditure productive?”, Journal of Monetary Economics 23(2): 177-200.

Auerbach, A J and Y Gorodnichenko (2012), “Measuring the Output Responses to Fiscal Policy”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(2): 1-27.

Baxter, M and R G King (1993), “Fiscal Policy in General Equilibrium”, American Economic Review 83(3): 315-34.

Blanchard, O and R Perotti (2002), “An Empirical Characterization of the Dynamic Effects of Changes in Government Spending and Taxes on Output”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1329-1368.

Boehm, C (2019), “Government Consumption and Investment: Does the Composition of Purchases Affect the Multiplier?” Forthcoming in Journal of Monetary Economics.

Christiano, L, M Eichenbaum, and S Rebelo (2011), “When Is the Government Spending Multiplier Large?”, Journal of Political Economy 119(1): 78-121.

International Labour Organization (2011), “A review of global fiscal stimulus”, European Commission-International Institute for Labour Studies EC-IILS joint discussion paper series no. 5.

Mankiw, N G (1985), “Consumer Durables and the Real Interest Rate”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 67(3): 353-62.

Kraay, A (2012), “How large is the Government Spending Multiplier? Evidence from World Bank Lending”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(2): 829-887.

Krugman, P (2016), “A Pause That Distresses”, The New York Times, 6 June.

Ramey, V A (2011), “Identifying Government Spending Shocks: It's all in the Timing”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(1): 1-50.

Endnotes

[1] This information is taken from The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act website. Since the website is now offline, I accessed a cached version (dated 4 January 2014) at The Internet Archive.