The future is unknowable, but also inevitable. This conundrum – we must think ahead, but we can’t be certain about our thinking – leads us to shy away from it. By training and temperament, we are more comfortable with historical data and time-honoured models. That won’t work this time.

COVID-19 is changing the world faster than most expected and in ways few anticipated. The US’s “Pandemic Influenza Plan: 2017 Update” covers all manner of medical issues, and even legal issues, but the word ‘economic’ appears only five times in the 53 pages. The 2005 “National Strategy for pandemic influenza” mentions it six times in 17 pages – almost always in the context of something vague like “health, social and economic impacts.” The idea that America would need a $2 trillion package in the first-round response to a pandemic was not thought out in advance.

The US’s “Pandemic Influenza Plan: 2017 Update” covers all manner of medical issues, and even legal issues, but the word ‘economic’ appears only 5 times in the 53 pages … The idea that America would need a $2 trillion package … was not thought out in advance.

This column speculates about the unknowable future that I think is inevitable – the Great Trade Collapse of 2020.

When leaping mentally into the future, it’s best to get a running start with a quick trot through the past.

The Great Trade Collapse of 2008 Q4 to 2009 Q4

The “Great Trade Collapse” was extensively documented in a VoxEU.org eBook that I edited in November 2009 (Baldwin 2009). Three facts suggest why the ‘Great Trade Collapse’ moniker stuck.

Fact #1: It was unexpected and it was big.

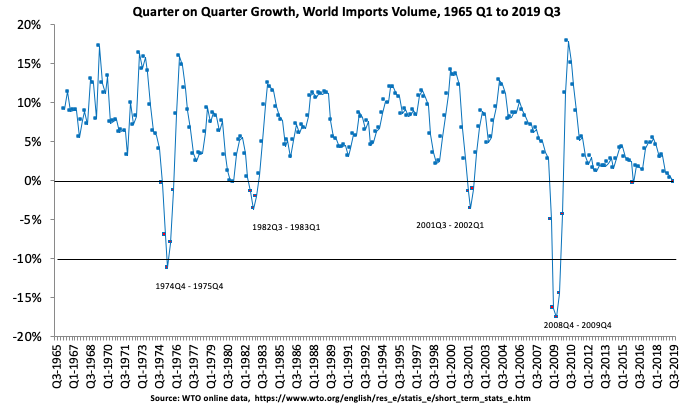

World trade had dipped into negative territory only three times from WWII to 2008 (during the oil-shock recession of 1974-75, the inflation-defeating recession of 1982-83, and the Tech-Wreck recession of 2001-02), so it was unexpected. Global trade growth has flitted briefly into the red twice since 2009 – but never for more than a quarter (Figure 1).

The 2008-09 fall was really big. It was not as deep as that of the Great Depression, but it was much steeper (Eichengreen and O’Rourke 2009). It took 24 months in the Great Depression for world trade to fall as far as it fell in the nine months from November 2008.

Figure 1 Historical world trade growth, 1965 – 2019

Source: Baldwin and Tomiura (2020) based on WTO online data.

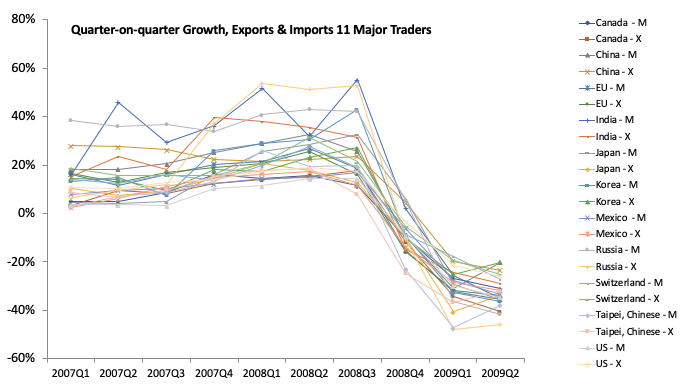

Fact #2: It was sudden, synchronised, and broad.

At the end of 2008, all nations reporting data to the WTO saw their imports and exports plummet. The chart (Figure 2) looks like a waterfall; imports and exports collapsed for the EU27 and ten other nations that together account for three-quarters of world trade. Each of these trade flows dropped by more than 20% from 2008 Q2 to 2009 Q2; many fell 30% or more.

Figure 2 The Great Trade Collapse, 2008 Q2 to 2009 Q2

Source: Baldwin (2009) based on WTO online database.

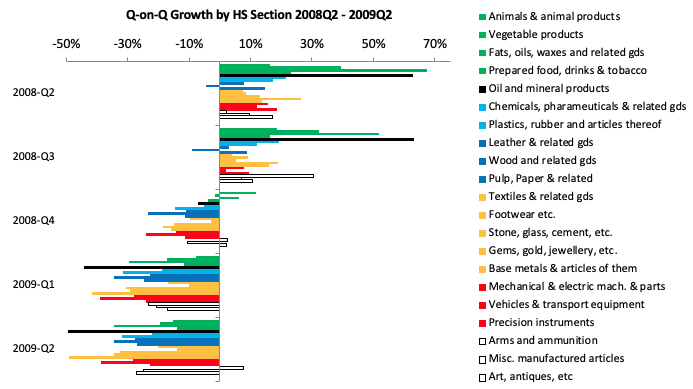

The drop was very broad, hitting sectors ranging from food and pharma to gems and guns. Figure 3 shows that world trade growth rates were positive in 2008 Q2 for almost all products; they were all negative by 2009 Q1. The categories of goods where global value chains were most important at the time (mechanical and electrical machinery, precision instruments, and vehicles) saw some big drops. The figure, however, shows that the falls were by no means extraordinarily large in these sectors.1 Things are different in 2020 (more on this below).

Figure 3 Trade in all types of goods collapsed simultaneously

Source: Baldwin (2009) based on WTO online database.

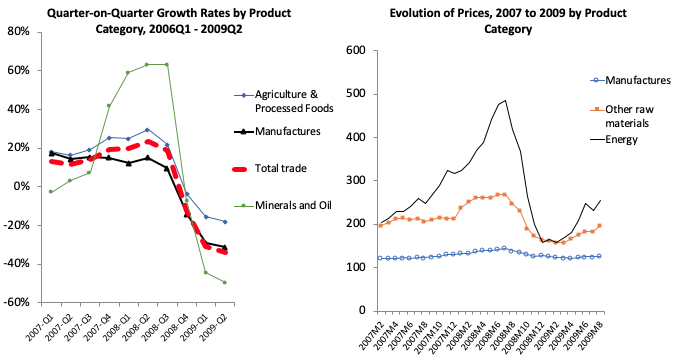

Fact #3: Commodities were hit harder.

Commodities back then were struck doubly hard since prices and volumes fell together. Starting from the end of a commodity super-cycle, the value of trade in minerals and oil fell faster than total trade as prices fell along with volumes (Figure 4). The price of manufactures, by contrast, was rather steady in this period even as volumes nosedived.

Figure 4 Prices and values in the Great Trade Collapse: Food, oil, and manufactures

Source: Baldwin (2009) based on ITC online database.

A key element of the Great Trade Collapse was a synchronised expectations shock. Psychologists tell us that people act in extremely risk adverse ways when gripped by fear of the unknown. Such fear typified the Fall of 2008. It really was a shock.

How the Subprime Crisis became the Global Crisis

The Subprime Crisis broke out in August 2007. For 13 months, it was viewed as a financial crisis afflicting North Atlantic nations who had badly mismanaged their regulatory affairs. But then the shock came – the Subprime Crisis metastasised into the Global Crisis on 15 September 2008. The financial world was flabbergasted; the rest of us were bewildered.

The Subprime Crisis broke out in August 2007. For 13 months, it was viewed as a financial crisis afflicting G7 nations who had badly mismanaged their regulatory affairs. But then the shock came – the Subprime Crisis metastasised into the Global Crisis on 15 September 2008. The financial world was flabbergasted; the rest of us were bewildered.

When the US Treasury let Lehman Brothers go under, things fell apart. Given the intertwining of counterparty risks, some financial institutions were bankrupt overnight. But no one really knew who these ‘some’ were. To be on the safe side, everyone stopped lending to anyone. Credit markets froze, but liabilities did not, so the ‘some’ became ‘most’.

And that was just one of a half dozen impossible events in the autumn of 2008. Here’s my favourite list of shockers. All big investment banks disappeared. The US Fed lent $85 billion to an insurance company (AIG) and had to borrow money from the US Treasury to cover it. A US money market fund lost so much that it could not repay its depositors capital. US Treasury Secretary Paulson asked the US Congress for a $750 billion bailout package – based on a three-page proposal about which he had difficulties answering direct questions, and then Congress said “no” (at first). Some European banks, which were too big to fail, turned out to be too big to save. Their assets had been allowed to grow to multiples of their home nations’ GDPs. In attempting to bail out their banks, nations like Ireland and Iceland went broke themselves.

If ever there was a time to reel and ‘wait and see’, the autumn of 2008 was that time. People around the world watched the unsteady and ill-explained behaviour of the US government. A massive feeling of insecurity and anxiety emerged. None of this was good for economic activity, especially not trade. Two-thirds of trade is made up of manufactured goods whose purchases can be postponed.

If ever there was a time to reel and ‘wait and see’, Fall 2008 was that time. People around the world watched the unsteady and ill-explained behaviour of the US government. A massive feeling of insecurity and anxiety emerged. None of this was good for economic activity, especially not trade.

Causes of the Great Trade Collapse of 2008-2009

The lion’s share of the collapse was driven by a massive demand shock which was in the first instance caused by the wait-and-see reaction.2 At first, the supply sides of most economies were unscathed. This is a key difference to today’s shock, so it’s worth taking a closer look.

The Global Crisis started with ‘financial cardiac arrest’. It was a supply-side hit, but quite limited – and this in two ways.

- The lightning struck the financial sector and nothing else (to start with).

The Lehman crashed caused an ‘economic heart attack’ and that, in turn, did massive damage to the real economy. As MIT Professor Ricardo Caballero put it in a famous 17 November 2009 VoxEU column: “Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is a condition in which the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. When this happens, blood stops flowing to the brain and other vital organs … SCA usually causes death if it’s not treated within minutes”. Caballero called the Global Financial Crisis a sudden financial arrest (SFA).

- The financial aspects of the Global Financial Crisis were geographically limited.

Back then, the financial sectors of most nations were not sophisticated enough to have set up ‘shadow banks’, to have been involved in subprime shenanigans, or to have issued mortgages to NINJA investors (in the US, NINJA stood for ‘no income, no job, and no assets’). Those things were the exclusive purviews of clever financial innovators in advanced economies.

… at first the crisis was a landmine upon which the US and European economies had, tragically, trodden … emerging nations thought of themselves as only indirectly concerned. But then the crisis spread at the speed of fear – firms and customers shelved investment and spending plans. The ‘landmine crisis’ became a ‘cluster-bomb crisis’ – throwing recession-inducing projectiles in every direction. The bomblets decimated all the world’s trade flows at once.

For the first few months, the crisis was thought of as a financial crisis – and mostly confined to the G7 economies. To use a military analogy, at first the crisis was a landmine upon which the US and European economies had, tragically, trodden. Because the landmine had also been ‘planted’ by US and European financial markets, Brazil, India, China, South Africa and other emerging nations were bemused and thought of themselves as only indirectly concerned. But then the crisis spread at the speed of fear – firms and customers drew back investment and spending plans. The ‘landmine crisis’ became a ‘cluster-bomb crisis’ – throwing recession-inducing projectiles in every direction. The bomblets decimated all the world’s trade flows at once.

The Greater Trade Collapse of 2020

In today’s COVID Crisis, we have all the makings of the 2008-2009 demand side shock, but on top of that we have massive, supply-side shocks across most sectors of most major economies. Taking just the US, China, Japan, Germany, Britain, France, and Italy, the stricken economies account for 60% of world supply and demand (GDP), 65% of world manufacturing, and 41% of world manufacturing exports.

In today’s COVID Crisis, we have all the makings of the 2008-2009 demand side shock, but on top of that we have massive, supply-side shocks across most sectors of most major economies … The 2020 trade collapse will be big, sudden, synchronised and broad – but it should not be unexpected.

The 2020 trade collapse will be big, sudden, synchronised and broad – but it should not be unexpected. The world is experiencing a massive, difficult-to-comprehend shock that has scared consumers and investors into a wait-and-see crouch. It is not quite like 2009 – the Queen is not going to ask: “Why didn’t anybody see this coming?”, since pandemic scenarios foresaw this one pretty well – but the size, speed and nature of the pandemic blindsided most economic agents. But there’s more this time.

This crisis is also accompanied by a massive supply-side shock. The supply-side ‘lightning strike’ is not limited to one sector, or to one geography. The virus – or more precisely, the government containment policies meant to combat COVID – is keeping workers away from work, and consumers away from consumption in a very direct, sudden, and synchronised manner. Production in almost all sectors has been shut down or severely curtailed. China’s manufacturing may be on the mend, but easing the supply-side constraints brings it up against the demand-side shock.

On top of all this – but perhaps not coincidentally – oil prices have plummeted as Saudi Arabia has chosen now to try to drive American shale oil and gas producers (fracking companies) out of business by bringing prices far below the newcomers’ breakeven points. A drop in price, timed with a perfectly predictable plunge in demand, may see American shale producers turning belly up in just a few quarters. While the storyline behind oil’s plunge is unique, commodity prices are softening in the COVID crisis as always happens in recessions - apart from some food crops, which are being hoarded/stockpiled by people and nations (Terazono 2020).

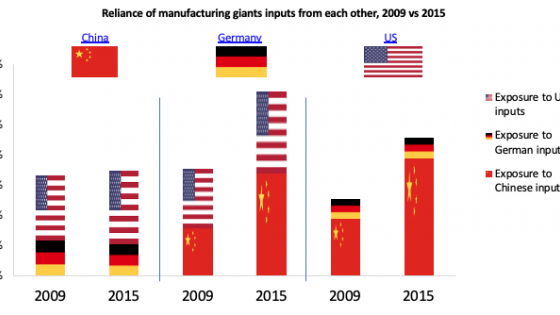

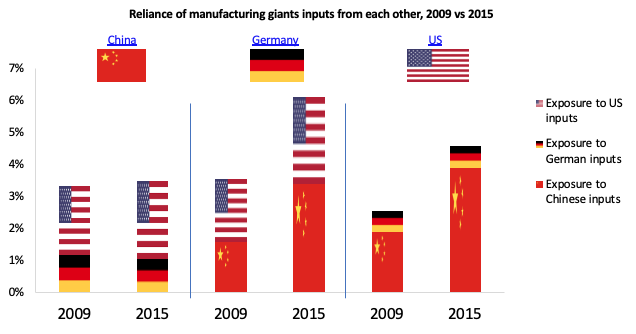

Supply-chain contagion was not a major amplifier of the 2009-08 trade catastrophe since the demand shock back then was globally synchronised; producers everywhere shut down together. This time, the fact that the pandemic first struck ‘Factor Asia’, then struck ‘Factory Europe’, and then struck ‘Factory North America’ is creating a separate cause of collapse (Baldwin 2020). Manufacturing sectors in less-affected nations are finding it harder and/or more expensive to acquire the necessary imported industrial inputs from the hard-hit nations, and subsequently from each other. As Figure 5 shows that for the three global manufacturing hubs – China, Germany and the US – interdependence on international supply chains has increased substantially for Germany but less so for the US and especially China.

Figure 5 Global manufacturing hubs’ interdependence

Source: Computations by author and Rebecca Freeman using OCED Inter-Country Input Output Tables Available online at https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/inter-country-input-output-tables.htm.

The increased dependence is really increased interdependence. As the calculations in my last Vox column showed, manufacturers around the world rely on Chinese inputs, but Chinese manufacturers rely on inputs from the US and Germany. This suggests that the Greater Trade Collapse of 2020 may have wave-like properties – not unlike the wave-like pattern of the pandemic that some epidemiologists are predicting. As China gears back up having mastered the first epidemic wave, the explosions of cases in the two other manufacturing giants, Germany and America, are likely to create reverse supply-chain contagion – the industrial equivalent of reinfection.

Concluding remarks

What are the learnings from the Great Trade Collapse? All nations will see their exports and imports fall in tandem as in 2009. The dollar-value downswing will hit most sectors at the same time, but it will probably hit commodities more than manufactured goods since prices and quantities will be slashed. Since proportional reductions in the levels of imports and exports shrink their difference, trade balances will all swing toward zero (Baldwin and Taglioni 2009).

The trade crisis, in domino fashion, is likely to tip emerging markets into further crises. Evaporation of dollar export earnings is likely to trigger sovereign debt crises in vulnerable emerging markets. That, in turn, could prove a problem for leaders who lent to them. Lastly, protectionist instincts may be reinforced by the looming disintegration of world trade growth.

One huge difference is the lack of leadership. In 2009, leaders like Gordon Brown, Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, Manmohan Singh and others held the first Leaders’ Summit of the G20 (a group formed after the 1999 Asian financial crisis for finance ministers and central bank governors to meet). National leaders agreed that protectionism should be avoided so as to ensure that the first Great Recession did not become the second Great Depression. Today, the US – led by a feckless, know-nothing government with an instinctive aversion to multilateral cooperation and an ongoing war against world trade – will not form the committee to save the world. Leaders around the planet will have to form a committee of all-but-one to make sure the looming 2020 trade collapse doesn’t trigger snowballing crises that allows the economic downturn to outlast the medical crisis.

References

Alessandria, G, J P Kaboski and V Midrigan (2010), “The great trade collapse of 2008–09: An inventory adjustment?”, IMF Economic Review 58(2): 254-294.

Altomonte, C, F Di Mauro, G Ottaviano, A Rungi and V Vicard (2012), “Global value chains during the great trade collapse: a bullwhip effect?”, in Firms in the international economy: Firm heterogeneity meets international business, pp. 277-308.

Auboin, M (2009), “The challenges of trade financing”, VoxEU.org, 28 January.

Baldwin, R (1988), “Hysteresis in Import Prices: The Beachhead Effect”, American Economic Review 78(4): 773-785.

Baldwin, R (2020), “The COVID concussion and supply-chain contagion waves,” VoxEU.org, 01 April

Baldwin, R and D Taglioni (2009), “The illusion of improving global imbalances,” VoxEU.org, 14 November.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020b), Mitigating the COVID economic crisis: Act fast and do whatever it takes, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Baldwin, R and B Weder Mauro (2020a), Economics in the Time of COVID-19, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Baldwin, R and E Tomiura (2020), “Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19,” Chapter 5 in Baldwin and Weder di Mauro (2020a),

Baldwin, Richard (ed.) (2009), The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects, A VoxEU.org Publication, 27 November 2009.

Baldwin, R and D Taglioni (2009), “The illusion of improving global imbalances”, VoxEU.org, 14 November.

Baldwin, R and S Evenett (2009), The collapse of global trade, murky protectionism, and the crisis: Recommendations for the G20, A VoxEU.org Publication.

Bean, C (2009), “The Great Moderation, the Great Panic and the Great Contraction”, Schumpeter Lecture, European Economic Association, Barcelona, 25 August 2009.

Bems, R, R C Johnson and K M and Yi (2010), “Demand spillovers and the collapse of trade in the global recession”, IMF Economic Review 58(2): 295-326.

Bems, R, R C Johnson and K M Yi (2013), "The Great Trade Collapse," Annual Review of Economics, Annual Reviews 5(1): 375-400,.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, Y Decreux, L Fontagné and D Khoudour-Casteras (2009), “Economic crisis and global supply chains”.

Blanchard, O (2009), “(Nearly) nothing to fear but fear itself”, Economics Focus column, The Economist print edition, 29 January.

Bricongne, J C, L Fontagné, G Gaulier, D Taglioni and V Vicard (2012), “Firms and the global crisis: French exports in the turmoil”, Journal of international Economics 87(1): 134-146.

Caballero, R (2009a), “A global perspective on the great financial insurance run: Causes, consequences, and solutions (Part 2)”, VoxEU.org, 23 January.

Caballero, R (2009b), “Sudden financial arrest”, VoxEU.org, 17 November.

Chor, D and K Manova (2012), “Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis”, Journal of international economics 87(1): 117-133.

Crowley, M and X Luo (2011), “Understanding the Great Trade Collapse of 2008-09 and the subsequent trade recovery”, Economic Perspectives 35(2)L 44.

Di Giovanni, J and A Levchenko (2009), ”International trade, vertical production linkages, and the transmission of shocks”, VoxEU.org, 11 November.

Eaton, J, S Kortum, B Neiman and J Romalis (2016), “Trade and the global recession”, American Economic Review 106(11): 3401-38.

Eichengreen, B and K O’Rourke (2009), “A tale of two depressions: What do the new data tell us?”, VoxEU.org, updated March 2010.

Engel, C and J Wang (2011), “International trade in durable goods: Understanding volatility, cyclicality, and elasticities”, Journal of International Economics 83(1): 37-52.

Freund, C (2009a), “The Trade Response to Global Crises: Historical Evidence”, World Bank working paper.

Gros, D and S Micossi (2009), “The beginning of the end game…”, VoxEU.org, 20 September.

Levchenko, A A, L T Lewis and L L Tesar (2010), “The collapse of international trade during the 2008–09 crisis: in search of the smoking gun”, IMF Economic Review 58(2): 214-253.

O’Rourke, K H (2018), “Two great trade collapses: the interwar period and great recession compared”, IMF Economic Review 66(3): 418-439.

Rose, A and M Spiegel (2009), “Searching for international contagion in the 2008 financial crisis”, VoxEU.org, 3 October.

Terazono, M, H Saleh, and F Reed (20202), Countries follow consumers in stockpiling food, Financial Times, 5 April.

Yi, K-M (2009), “The collapse of global trade: The role of vertical specialisation”, in R Baldwin and S Evenett (eds), The collapse of global trade, murky protectionism, and the crisis: Recommendations for the G20, a VoxEU publication.

Endnotes

[1] The 2009 eBook has a chapter by Bems, Johnson and Yi that showed GVC sectors were hit harder controlling for other factors – this was published four years later in a standard journal.

[2] Formal empirical investigations of the Great Trade Collapse causes looked at the three leading hypotheses broached in the 2009 VoxEU eBook, namely the demand shock (Eaton et al. 2009, Bénassy-Quéréet al. 2009, Levchenko et al. 2010, Engel and Wang 2011), the trade finance shock (Chor and Manova 2010), and protectionism. Using detailed firm-level data, Bricongne et al. (2012) concluded that most of the collapse was due the demand shock and product characteristics, with credit constraints emerging as an aggravating factor. Protectionism rose, but not fast enough to explain the collapse (Baldwin and Evenett 2009).