The dramatic rise in multi-authored papers in economics is in itself a phenomenon of interest to economists. One issue of particular policy relevance, however, is how hiring and promotional bodies and funding agencies have responded to this change in the publication patterns of research economists. For example, to what extent do they apply, if at all, a discount for articles published with one, two, three, or more other researchers? Changes in this regard could be a key explanation for the phenomenon. But the existing literature has tended overwhelmingly to seek other explanations.

Perhaps the earliest substantive paper on this issue is McDowell and Melvin (1983), using just ten journals in their sample. Barnett et al. (1988) widen the discussion considerably, but using an even narrower dataset, namely, the AER alone. Their starting argument for the rise in multi-authored papers in economics is what they term the ‘division of labour’ hypothesis, very similar to the specialisation focus of the earlier McDowell and Melvin (1983) paper and taken up later by Jones (2009).

Another argument they and Hamermesh (2013) make is that the increasing emphasis on publication in refereed journals as a criterion for appointment and/or promotion allows less time to assist colleagues, the ‘reward’ of an acknowledgement or ‘thank you’ being replaced with the offer of co-authorship to elicit such assistance. This is their opportunity cost of time hypothesis, but it depends crucially on the discount factor applied, if any, to papers with more than one author. A more convincing hypothesis, perhaps arising from the increased ‘publish or perish’ pressure, relates to risk aversion, which says it is better to spread your risks by submitting, say, four papers by four authors than one solo-authored paper. Rosenblat and Mobius (2004) and Catalini et al. (2016) argue that advances in communication and transportation technologies have created a ‘global village’, increasing the possibilities, and hence the incidence, of multi-authorship. Using large datasets, Henriksen (2016) and Rath and Wohlrabe (2016) document further the scale and breadth of the rise in multi-authorship in the social sciences, including economics.

Drawing on this literature, in a recent paper we provide substantial new findings on the rise of multi-authorship in economics – findings which, by exploring the detail and nature of the rise, throw some light on the various explanations posited in the literature (Kuld and O’Hagan 2017).

Key findings

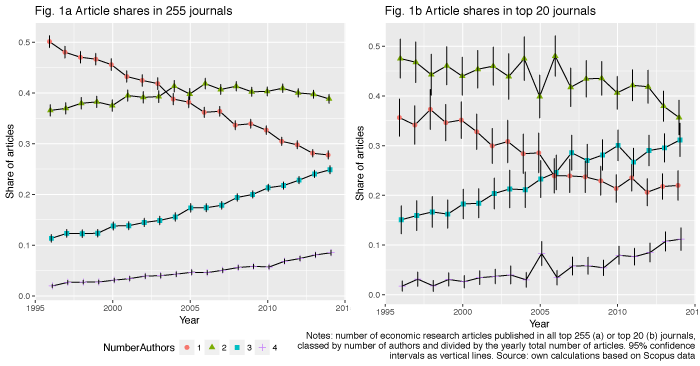

Figure 1 provides the picture of the overall trends in co-authorship in economics for the period covered. As recently as 1996, solo-authored papers accounted for 50% of all articles published in our sample, with this number dropping to just over 25% in 2014. While the share of two-author papers remained steady, the huge pickup was in papers with three authors and papers with four-plus authors, particularly the latter. The picture is replicated whether the data relate to all journals (top 255, Figure 1a) or the top 20 journals, but different trends are evident (Figure 1b).1 The rise of papers by three and four-plus authors is particularly marked in the top 20 journals, with just over 20% now solo-authored. If present trends continue, the number of papers with four or more authors could soon exceed the number of solo-authored papers.

Figure 1 Trends in co-authorship in economics

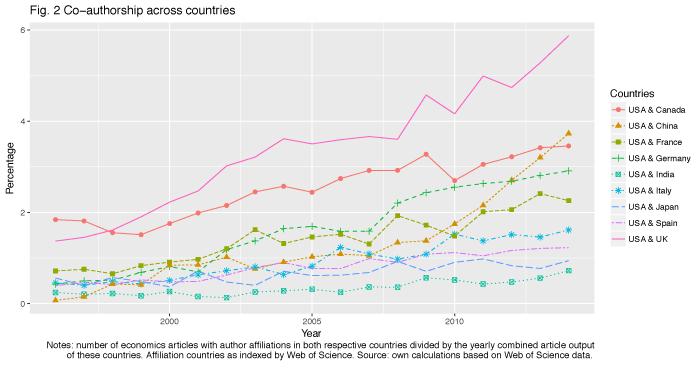

Turning now to the trends in co-authorship across countries, we examine co-authorship between US researchers and economists from other countries (Figure 2). Since 1990 there has been a very large rise in co-authorship across countries, especially between the US and the UK. The rises for the other country combinations are also large though, especially when expressed in percentage terms. This would tend to support the view that increased ease of communication and transport may have been key factors in the rise of multi-authorship.

Figure 2 Cross-country co-authorship

We also looked at citations by multi-authorship type and found significantly higher citations for papers by four or more authors, especially compared to single-authored papers. However, when this is adjusted to citations per author a very different picture emerges. Citations per article per author are much higher, and significantly so, for single-authored papers and this, one might argue, is the better indicator of the contribution of an individual to the field.2 This is true no matter which category of journal is used.

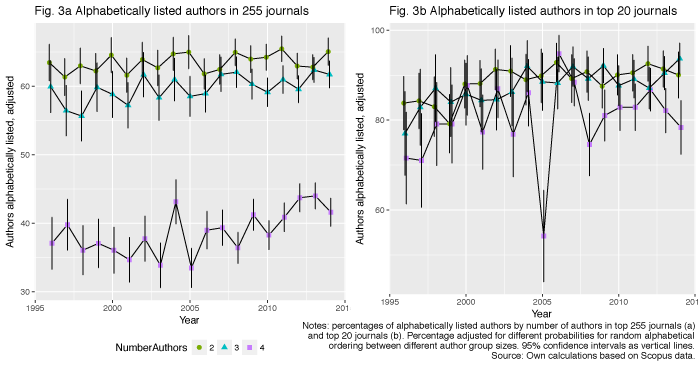

Another issue is the alphabetical ordering of author names on articles by author category. Figure 3 shows that there is a high proportion of articles using alphabetical ordering of names on the papers, even if adjusted for random alphabetical ordering. The figure is around 60% for papers by two and three authors, but only around 40% for papers by four authors. However, importantly these percentages did not vary much over the period examined.

Figure 3 Authors’ alphabetical ordering on articles

The alphabetical ordering of names is particularly high in the top 20 journals, with no significant differences evident by number of authors. This implies that the contribution of each author is signalled to be approximately equal. In addition, this makes it impossible to directly identify roles within the author team, for instance the lead author listed first or the group supervisor listed last. In turn, this increases the costs of token-adding of names of supervisors or researchers who made no significant methodological or other contribution.

One further chart of interest relates to the career profile of top economists who were awarded their PhD between 1996 and 1999. Figure 4 plots the articles by number of authors for 133 top economists in the years following their PhD graduation. As can be seen, the propensity for solo-authored papers by these economists is highest in the first five career years, and thereafter the ratio to multi-authored publications is similar to all articles in top-20 journals.

Figure 4 Articles by number of authors for top economists

Explanations

Specialisation in the context of co-authorship could relate, as discussed, to the benefit of specialised roles within an author team. Our empirical analysis provides no strong evidence for this hypothesis, but the argument has a strong basis a priori (see Barnett et al. 1988) and also some empirical support. For example, Henriksen (2016) shows that the most substantial rises in multi-authorship in the social sciences have occurred in subject categories where the research is often based on the use of experiments, large datasets, statistical methods, and/or team production models.

We also do not find a trend towards research teams in which team roles or contributions are signalled by the ordering of names. Figure 3 shows the high and unchanging incidence of the alphabetical listing of authors.

The internet and cheaper flights did lower the costs of communication and, subsequently, co-authorship between distant researchers. The evidence in relation to co-authorship across countries would tend to support the argument that technology and transport costs may have been key factors (see Figure 2), as do some of the studies listed earlier.

If the pressure on economists for more articles has increased over time, researchers can respond by increasing co-authorship. First, shared work should be less time-consuming than solo-authoring if there are gains from the division of labour. Second, if co-authored papers are not discounted by the numbers of co-authors, this would provide major incentives to co-author. In addition, co-authorship diversifies the risk of individual research projects failing.

However, the high incidence of solo-authored papers in the early career stages points towards the ambiguity of co-authorship in relation both to the increasing specialism argument above and also in the hiring process (see Figure 4). Interestingly, Sarsons (2017) shows that in tenure decisions, women receive less credit for co-authored work than men. It is likely that young authors are equally perceived as not fully contributing to co-authored work and, therefore, choose to solo-author.

Perhaps what is needed is more evidence on hiring, promotional, and funding decisions with regard to solo versus multi-authored papers. The patchy evidence would seem to suggest that there is very limited discounting of a published article by number of co-authors.

Ossenblok et al. (2014) analyse co-authorship patterns in the social sciences and humanities for the period 2000 to 2010. Two interesting things in this study are noteworthy here. The first is that the incentives for co-authorship have changed significantly. Output-based research funding offers researchers one of the most directly tangible publication incentives. Besides, it seems that the Flemish performance-based research-funding system actively encourages co-authorship through its use of whole counts (i.e. giving each institution full credit for an article that bears its name and address). This is opposed to systems that use fractional counts (i.e. counting an article as a single unit and fractionalising the publication credit).

We need much more information on how hiring and promotional bodies and funding agencies have responded to and/or caused the change in the journal article publication patterns of research economists. Only when we have this can we be any way sure about the relative importance of the factors looked at above in explaining these patterns.

References

Barnett, A H, R W Ault, and D L Kaserman (1988), “The rising incidence of co-authorship in economics: further evidence”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 70, 539-543.

Catalini, C, C Fons-Rosen, and P Gaule (2016), “Did cheaper flights change the direction of science?”, CEPR Discussion Paper 11252.

Hamermesh, D S (2013), “Six decades of top economics publishing: who and how?”, Journal of Economic Literature, 51 (1), 162-72.

Henriksen, D (2016), “The rise in co-authorship in the social sciences (1980-2013)”, Scientometrics, 107 (2), 455-476.

Jones, B F (2009), “The burden of knowledge and the ‘death of the renaissance man’: is innovation getting harder?”, Review of Economic Studies, 76 (1), 283.

Kuld, L, and J O’Hagan (2017), “Rise of multi-authored papers in economics: Demise of the ‘lone star’, and why?”, Scientometrics online.

McDowell, J M, and M Melvin (1983), “The determinants of co-authorship: an analysis of the economics literature”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 65, 155-16.

Ossenblok, T L B, F T Verleysen, and T C E Engels (2014), “Co-authorship of journal articles and book chapters in the social sciences and humanities (2000-2010)”, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65 (5), 882-897.

Rath, K, and K Wohlrabe (2016), “Recent trends in co-authorship in economics: evidence from RePEc”, Applied Economics Letters, 23 (12), 897-902.

Rosenblat, T S, and M M Mobius (2004), “Getting closer or drifting apart?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119 (3), 971.

Sarsons, H (2017), “Recognition for group work: gender differences in academia”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 107 (5), 141–145.

Sauer, R D (1988), “Estimates of the returns to quality and co-authorship in economic academia”, Journal of Political Economy, 96 (4), 855-866.

Sommer, V, and K Wohlrabe (2017), “Citations, journal ranking and multiple authorships reconsidered: evidence from almost one million articles”, Applied Economics Letters, 24 (11), 809-814.

Endnotes

[1] The charts for the top 50 journals are very similar to those for the top 20 and hence are not included in this paper.

[2] Sauer (1988) and Sommer and Sommer and Wohlrabe (2017) also examine this issue.