Since the Global Crisis, the ECB, like other central banks around the world, has used unconventional policies that rely on factors other than changes in interest rates to stimulate growth and meet its inflation target.

Questioning the effectiveness of monetary policy

These unconventional policies have included quantitative easing (QE) and negative interest rate policy (NIRP). The effectiveness of these policies has been questioned in many countries, not least in Europe (e.g. Den Haan 2016, Turner 2015, Joyce et al. 2012). Growth continues to disappoint and the threat of deflation remains. Because European growth and inflation remain low, the idea of helicopter money is slowly gaining traction with politicians and economists alike.

What is helicopter money?

Helicopter money refers to a policy whereby the central bank brings extra money into the economy to stimulate demand. The original idea was first raised by Milton Friedman in 1969. In the paper, The Optimum Quantity of Money, he stated:

“Let us suppose now that one day a helicopter flies over this community and drops an additional $1,000 in bills from the sky, which is, of course, hastily collected by members of the community.”

ING decided to examine this idea by asking people, directly through its ING International Survey programme, how they would react if the central banks across Europe were to put helicopter money into practice. Full details can be found in the ING International Survey special report, Helicopter Money 2016 (ING 2016)

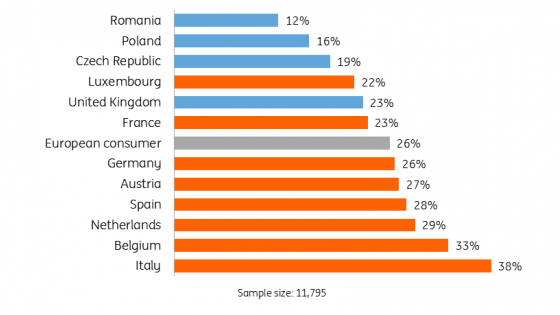

Almost 12,000 people in 12 countries across Europe were asked: “Imagine you received €200 in your bank account each month for a year. You are free to do what you want with the money and don’t need to repay it or pay taxes on it. How would you use this extra money?”

Conclusion: loved, not spent

The answers to this and other questions suggest the effectiveness of helicopter money “for the people” can be questioned. Few consumers say they would spend the money received. Only about one in four (26%) say they would spend most of the money. This share is very low, compared with alternative ways the money could be used. In addition, less than half believe either growth or inflation would be higher if the ECB created money in this way. Nevertheless, there is broad support for helicopter money. European consumers seem to be saying: “I will not spend it, the policy won’t work, but please give me the money anyway.”

The remainder of this column outlines the results of the survey in more detail

Only a quarter would spend the money

Our research shows that only a quarter (26%) of European consumers say they would spend most of the money, in a situation where they received €200 in their bank account each month for a year. The figure of €200 a month has comparability with the size of QE in Europe. Using Eurostat’s figure of 340 million as the population, total costs would be €816 billion a year, which works out to about €68 billion a month. This is roughly comparable with the current QE programme, which recently increased from €60 billion to €80 billion a month.

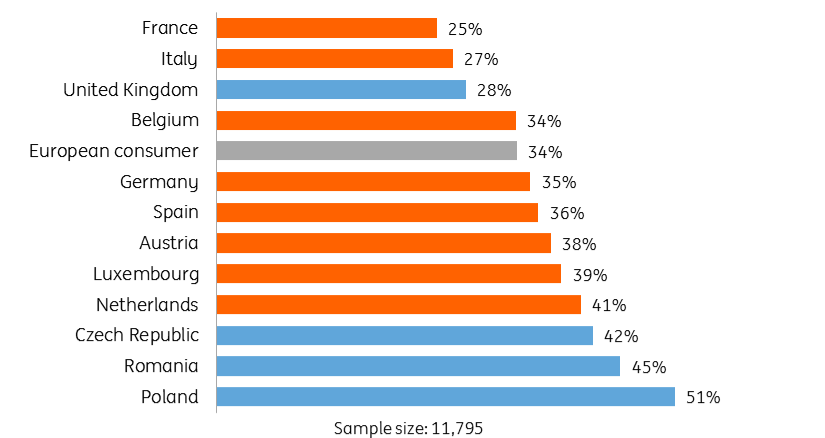

Figure 1. Imagine you received €200 in your bank account each month, for a year. You are free to do what you want with the money and don’t need to repay it or pay taxes on it. How would you use this extra money?

A majority (52%) would save it, invest it, or leave most of the amount in the account in which they received it. A further 15% would use most of it to reduce debt.

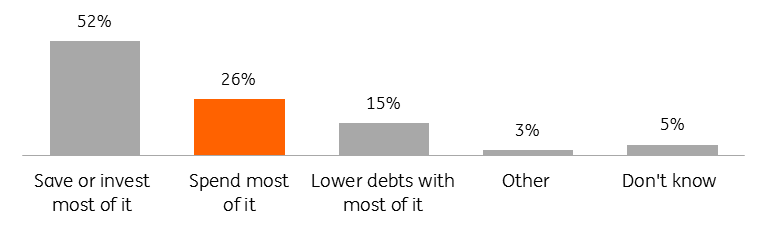

There are large differences across countries. Almost 40% of Italians would spend the money, while less than 20% of Romanian, Polish and Czech consumers would.

Figure 2. Percent who would spend most of the money, by country

The fact that this policy is likely to be used only in a situation of ‘economic emergency’ may make people doubtful. The concept of helicopter money may be so alien to them, that they might not be convinced they will never have to return the money, for instance in the form of higher taxes in the future. As a result, they may resort to saving instead of spending the money.

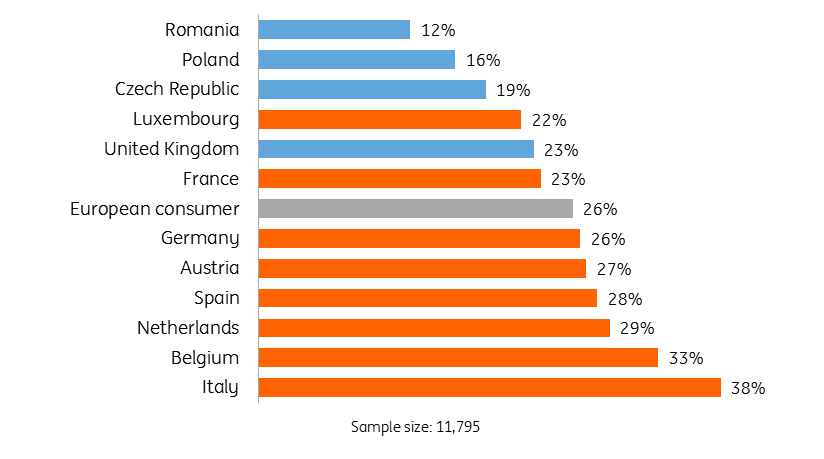

A majority of consumers expect no effect on prices

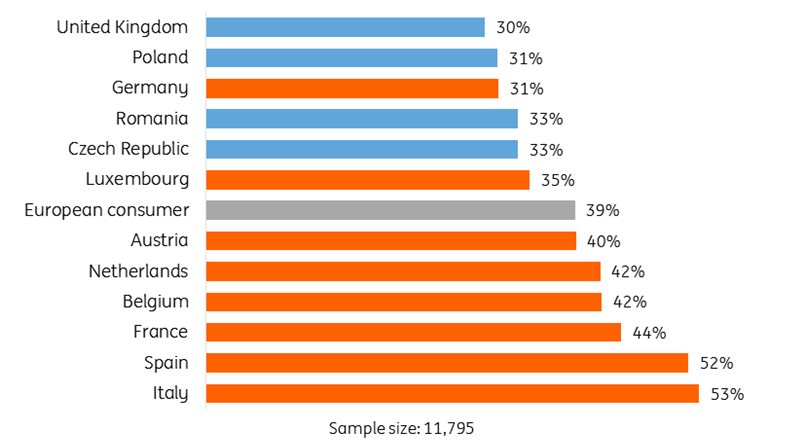

Most European consumers do not think helicopter money would lead to higher prices. More than 40% think prices would stay the same. Seven percent believe prices would decline; 17% don’t know.

Only one in three (34%) think prices will rise. Opinions vary widely between countries. Interestingly, the expectations of Germans almost equal the average European, while the German economy is performing at potential (low output gap) and unemployment is low. This is not consistent with economic theory.

Figure 3. What do you think will be the effects after 12 months if the ECB/central bank of your country distributed money in this way? Prices will be ... compared with not doing this.

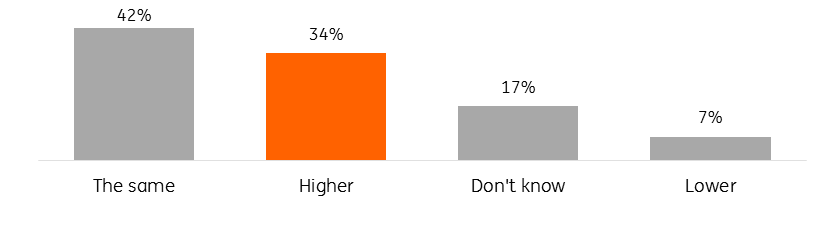

Figure 4. Percent who replied helicopter money would lead to higher prices, by country

Potential effects on growth

In order to determine the possible impact of helicopter money, the survey asked consumers separate and detailed questions about what proportions they would spend, save, invest or use to reduce debt.

Answers to these questions indicated the average European consumer would spend 24% of the money they received.

Imagine the ECB handed money to all Eurozone citizens and citizens did actually spend 24% of it. This could result in increased consumption of €576 a year per Eurozone citizen (€200 x 24% x 12 months = €576).

Since actual consumption per capita in the Eurozone is about €17,000, this could result in an extra consumption impulse of at least three percent.

The size of this consumption impulse would be almost 2% of euro area GDP. However, the final impact of this impulse on economic growth is dampened by import leakages. On the other hand, positive second order effects may exist. A precise effect is therefore difficult to determine.

There are additional limitations in estimating the exact growth effect.

- First, the fact that the central bank hands out the money and not somebody else could trigger consumer caution. Indeed, 23% of consumers report they would be more reluctant to spend the money if it were the ECB that handed it to them.

- Second, consumers could also use the money to buy things that were already on their lists to buy in the near future. This would lead to a temporary rise of consumption in the year of the hand-out, followed by a decline in the next year. Consumption (and growth) would only shift in time. Research (Hsieh et al. 2010) on Japan’s 1999 shopping coupon programmes gives empirical proof that these shifts indeed occur.

Respondents to the survey doubt the effect on economic growth

To supplement these calculations, we asked people for their opinion of the effect on growth. Most European consumers do not think helicopter money will lead to more growth.

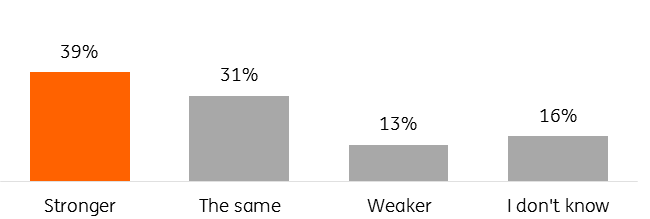

Thirty-one percent say growth would be the same over the following 12 months and 13% think it would be weaker; only 39% expect growth to be stronger.

In Southern Europe, people are more positive. Years of economic hardship during the crisis could explain why they are more confident about the positive economic impact of helicopter money than others. It’s also consistent with economic theory: the amount of spare capacity in their economies is higher than in countries where unemployment is low (e.g. Germany).

Figure 5. What do you think will be the effects after 12 months if the ECB/central bank of your country distributed money in this way? Economic growth will be ... compared with not doing this

Figure 6. Percent who replied helicopter money would lead to stronger economic growth, by country

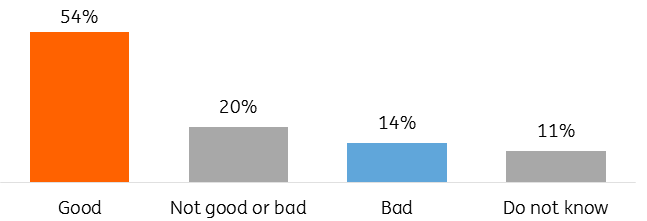

Majority in favour of helicopter money policy

Despite respondents to the survey believing there would be a sustained increase in growth or prices, a majority (54%) of European consumers think helicopter money is a good idea. Only 14% are opposed. 31% think it’s neither good nor bad or don’t know. They seem to be saying: “Give me the money anyway so I can save it.”

Figure 7. To what extent do you think it is a good or bad idea for the ECB/central bank of your country to distribute money to all people aged 18 years or older (a policy often referred to as helicopter money)? I think the idea is …

The strength of helicopter money is that it can deliver direct benefits to consumers. For people with less income, €200 a month extra can be a very welcome amount to make ends meet.

Other measures may have larger growth impact

Economic theory and empirical studies show that lower taxes have less impact on short-term economic growth than higher government expenditure (Barrell et al. 2012) (due to saving and investing). Our study suggests consumers would spend only a small part of the money handed to them. To increase the share of helicopter money spent, an alternative could be to hand out time-limited spending coupons that could only be used by the owner of the coupon (to prevent selling). Given the reluctance of consumers to spend helicopter money, this suggests that a larger impact might be achieved if it were given to the government to finance projects.

References

Barrel, R, D Holland, and I Hurst (2012), “Fiscal Consolidation: Part 2. Fiscal Multipliers and Fiscal Consolidations” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No 933, OECD Publishing.

Den Haan, W (ed) (2016), Quantitative Easing: Evolution of economic thinking as it happened on Vox, VoxEu.org eBook, Part II. http://voxeu.org/content/quantitative-easing-evolution-economic-thinking-it-happened-vox

Friedman, M (1969), The Optimum Quantity of Money, London, Macmillan..

Hsieh, C-T, S Shimizutani and M Hori (2010), “Did Japan’s shopping coupon program increase spending?” Journal of Public Economics, 94, pp 523-529.

ING (2016), Helicopter Money 2016, an International Survey special report. https://www.ezonomics.com/ing_international_surveys/helicopter-money-2016/

Joyce, M, D Miles, A Scott, D Vayanos (2012), “Quantitative easing and unconventional monetary policy – An introduction”, The Economic Journal, 122 (November) F271-F288.

Turner, A (2015), “The Case for Monetary Finance - An essentially Political Issue” Paper presented at the 16th Jacques Polack Annual Research Conference, hosted by the International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC November 5-6.