Help-to-Buy was set up to stimulate the economy and help working people buy a home. Critics worry that it has no supply effect and thus just pushes up house prices. This column argues that the policy will boost supply and that it could also become a useful macroprudential tool. The Financial Policy Committee, in conjunction with others, could adjust parameters to manage volatility and avoid bubbles.

Four reasons why Help to Buy in the UK should be positive:

- It will help address to a gap in the market for affordable housing.

- Supply-side dynamics should respond from historically low levels to this stimulus if house builders have confidence in its duration.

- The private sector could take over some or all of this role after year 3 – by privatisation of the nascent mortgage indemnity insurer, by introducing private competition, or via re-insurance.

- It could be used as a powerful macro-prudential tool. Regardless of whether it remains a government vehicle, we think the FPC should retain control over the key parameters – and the Canadian experience shows a possible role for tweaking terms.

The exit / retention strategy and how it dovetails with planning need to be spelled out early to maximise the multiplier to the real economy. Policy makers need to manage the scheme’s cliff risks and execute its smooth transition into the private sector. The lead-time to bring a new build to sale completion is 12 months, plus additional time for planning approvals, so maximum supply side impact from the scheme will require a view within 18 months.

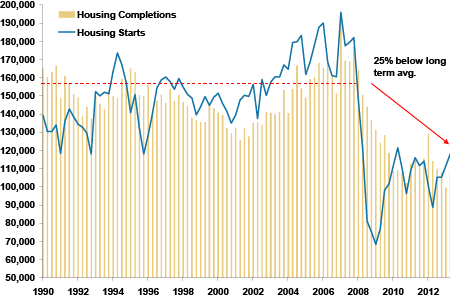

Figure 1. Housing starts and completions in England are ~25% below the LT average – so could rise by one-third to 20-year pre-crisis average. This would come after an 18% increase already on the 2012 avg.

Source: ONS, Morgan Stanley Research. Data as at Q2 2013. Note that quarterly data has been annualised in this chart.

Help to Buy scheme – An anatomy

There are actually two elements of the ‘Help to Buy’ scheme. The first tranche is in the form of an equity loan scheme, which was launched in April this year. The second is the mortgage guarantee scheme on which we focus in this column.

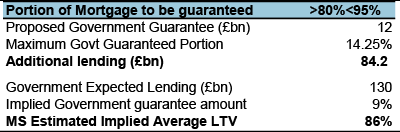

The Government’s estimate of £130 billion of new lending on the back of the guarantee scheme encompasses the assumption that not all of the guarantee uptake will be executed at the maximum level – e.g. 14.25%. Looking into the numbers in more detail, if the maximum guarantee were to be applied to all loans, then there would be £84 billion of new lending, which is some £46 billion short of the government’s estimate. Backing out the implied guarantee from the £130 billion, we estimate that the government will provide for about 9% of the loan, equating to an 86% loan-to-value ratio on average.

Table 1. £130bn of new lending implies average LTV of 86%

Source: HM Treasury, Morgan Stanley Research estimates.

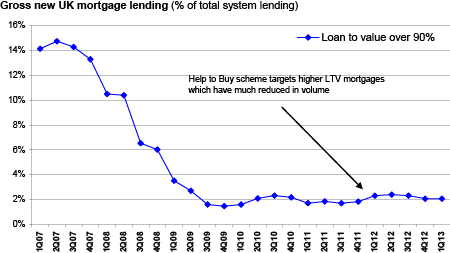

In the UK, the above 90% loan-to-value segment in UK mortgage lending has contracted significantly from about 14% of the market to about 2% of the market currently. Clearly, it would not be desirable to return to the Northern Rock era of high loan-to-value lending, with borrowers just hoping for capital appreciation. However, it could go some way to addressing the issue of ‘pent up demand’ where creditworthy borrowers who can afford a capital and repayment mortgage cannot access finance as they do not have enough cash for the substantial upfront deposit now required by most banks.

Figure 2. Help to Buy should stimulate lending at higher LTVs, although we expect 80-90% to be the sweet spot

Source: Morgan Stanley Research, Bank of England

Widening access to housing

Help to Buy can increase the availability of loans for affordable housing. Such mortgage indemnity insurance in the UK should, therefore, help to increase the availability of loans for affordable housing, since it addresses a current gap in the market for higher loan-to-value loans.

With material ongoing changes in bank regulation, the cost and availability of 80-95% mortgages has become dramatically tougher. To a large extent, this is the result of the Financial Services Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority intentionally putting much harsher capital charges against these loans, although it also reflects some risk aversion by banks, given the present numerous uncertainties. For instance, our discussions with the banks suggest that a 95% loan to value mortgage was being priced at about 1.5% per annum more than a 75% loan to value loan, although the estimated additional credit charges only amount to 25 basis points, according to one leading bank. This is primarily due to higher regulatory demands. In addition, the number of loans written in these categories, as we show later, has fallen to very low levels. By somewhat de-risking high loan-to-value mortgages from a lender (and, we assume regulatory) perspective, some of these problems should ease.

Increasing supply

The policy can also boost housing supply – critical to an economic recovery. The main criticism of the guarantee initiative is centred around the idea that it will not boost supply, and rather will only serve to pump up house prices further. We disagree. Moreover, we think house building – as in the 1930s – is critical to a broader economic recovery.

The growing rehabilitation of the banks and the economy, plus policies like funding for lending, have already led to a pick-up in demand for first time and buy to let mortgages, as well as higher sales expectations at house builders. With the addition of Help-to-Buy, we think that this could be the trigger for a further supply side revival. At this stage, the government estimates that £12 billion of funding should catalyse £130 billion of new lending for both new and existing housing – about a 10% increase in the stock of lending, should it all come to fruition. This is in addition to the £3.5 billion equity segment of the scheme, which was introduced in England in April and applies solely to new housing. Further, the policy has the makings of a potentially powerful macro-prudential tool, which could be deployed to reduce rather than raise the risks of a housing bubble. Having more new, affordable homes is clearly also good for the UK, well beyond the GDP impact. We expect that the majority of mortgages under the scheme to be in the 80-90% range, as in Canada and Australia. As analysed above, backing out HMT’s numbers, we estimate HMT is assuming a mean of 86% loan-to-value ratio.

30-40% increase in English housing starts by 2015 looks possible

Housing starts and completions in England are running 25% below the long-term average (using the 20 years pre crisis), despite already bouncing 15% in the first half of this year from the average of 2012 levels. Reverting to the long-term mean could imply a one-third increase in housing starts and completions. To put this in context, in 2012 there were approximately 100,000 housing starts and in first half of 2013 they are running at an annualised rate of 115,000. The long-term average pre-crisis we calculate to be about 155,000, and our conversations with leading house builders suggest that it would not be implausible for them to close this gap, in part thanks to larger land banks – although planning rules and supply chain bottlenecks clearly remain a key constraint.

Our conversations with CEOs/CFOs at UK house builders point to a higher potential supply response. We have already seen an approximate 30% pick-up on average in reservations of new builds on the back of the equity loan segment of Help-to-Buy, but this could be just the first wave. Our interviews suggest that the house builders are expecting to see an uplift in supply volumes. Looking across the land bank data for the six largest house builders, there is certainly capacity to grow supply.

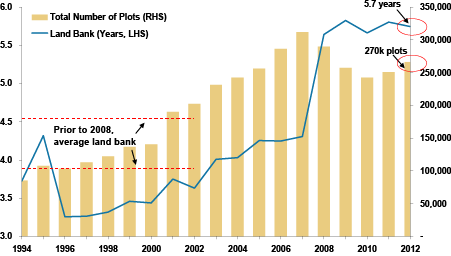

Figure 3. Large land banks are ready to be deployed. A return to historical levels could imply ~100k new properties or ~1 year supply on current completion levels

Source: Company Data, Morgan Stanley Research. Based on simple average of land bank data taken from: Taylor Wimpey, Persimmon, Barratt, Redrow, Bovis & Bellway. Data as at FY2012.

Our estimates show that average land banks are running at 5.7 years of average stock versus 3.8 years for the prior 15 years. If these stocks returned to previous levels, we could see an additional 100,000 houses being built, which equates to about a year’s supply based on current completion rates.

However, the supply side has been weakened post crisis, and more could be done. Clearly, house builders took a huge hit in the downturn, and capacity has been lost in some parts of the supply chain. As a result, it will take time for capacity to be rebuilt, although there are some recent positive signs. For instance, there has been a 21% increase in construction apprenticeships in the first half of 2013 – per Construction News August 2013. Planning is the area where policy makers need to be most effective, but there are other areas too. For instance, Housing Associations are far less keen to build, given that they have less access to finance these days. One by-product of bank regulation has been to create massive disincentives for long-dated loans to social housing. Every bank we speak with is reducing its book. Enabling larger social housing projects to be able to access insurance or broader market finance seems desirable, although this will require further policy changes.

Wider effects on the economy

Any improvement in residential construction could add to ‘escape velocity’. Construction has been a significant drag on overall GDP growth for much of the post-crisis period. Although only 16% of total construction, residential construction has a potentially sizable role to play in the recovery. For example, in the first half of 2013, looking at the expenditure side of the GDP accounts, residential investment already contributed 0.2% to GDP growth, where GDP only grew 0.3%.

Housing transactions are positively correlated with consumer spending. Housing transactions should pick up, and there is naturally a positive correlation between housing transactions and some elements of consumer spending (particularly spending on furnishings and household equipment).

Figure 4. More housing transactions … more furniture sold

Source: ONS, Morgan Stanley Research

Use of similar schemes elsewhere

Schemes such as Help-to-Buy are widely used in comparable countries, including Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, Mexico and several others. Although mortgage indemnity insurance is compulsory in Canada for high loan-to-value mortgages, it is notable that some two-thirds of the values of all mortgages are insured. In Australia, where it is voluntary, we estimate that about one third are. There have been plenty of mistakes, most notably with Freddie and Fannie in the US, and hence we think using the private sector rather than relying on the government long term also makes sense. There is much to be learned from past mistakes when designing the scheme, including the issues Eagle Star and others had in the early 1990s. The Basel Committee working paper in April also noted aspects of best practice, which the UK could adopt.1

Regional effects

The equity scheme appears to have had bigger impacts beyond London – where the regional economies sorely need more impetus. In the first wave of new build properties reserved under the equity loan leg of the scheme, the largest share has been in the Midlands, with 7% in London (versus 15% of second quarter housing completions). The mortgage indemnity leg of the scheme may, however, not have such striking differential ratios, given of course new house supply is more constrained in London than in the rest of the country. With the inclusion of existing housing in the guarantee scheme, therefore, the impact in London could be greater.

What happens later?

But question marks persist over ‘cliff risk’. Policy makers need to get ahead of ‘cliff risk’ as well as get the contractual terms right. The key to whether this policy succeeds is whether it drives greater supply, and this will only happen if the house builders are confident that new properties coming to the market further down the line will be marketable. Currently, the scheme is only proposed for three years. The average time to build and sell a new house, including planning constraints, is around 18 months, so if uncertainty around the duration of the scheme persists, then house builders may cut supply back substantially during the second year, thus diluting the desired multiplier effect to the economy. It would be helpful to take a decision on the scheme within 18 months, rather than three years.

Private sector operation?

Greater private sector involvement has been the exit route of choice for a number of global schemes. This could help address the ‘cliff risks’. Mortgage guarantee schemes are not a new concept, though their global implementation has varied over time, with some opting for full state control – such as Hong Kong – and others partially state controlled – Canada. The most notable example of a full, successful privatisation was Australia in 1997, when the Housing Loans Insurance Co-operation (HLIC) was purchased by GE Capital. Today, six players make up the wholly privatised industry, which is highly regulated by APRA (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) with solvency coverage ratios of about 150%. It would certainly make sense for the UK to get ahead of market concerns and think about the next step for the scheme, once the state-backed phase rolls off. Recent reports (FT, August 4th) indicate that the Treasury has been holding talks with several insurers, including Genworth.

Conclusion

Help-to-Buy has the potential to become a useful macro-prudential tool. Policy makers will understand at first hand the perils of a housing bubble, and thus will be mindful of the pitfalls associated with the scheme – but Help to Buy could become a useful macro-prudential tool. The FPC in conjunction with other parties could change the parameters of the scheme counter-cyclically to manage bouts of housing market and mortgage market volatility. Put differently, this scheme would mean that banks no longer have mortgages with LTVs above 80% on average and that policy makers would be able to control the grid of a conforming mortgage.

Charles Goodhart is a senior adviser to Morgan Stanley. In his personal capacity, Mr. Goodhart advises other organizations and firms on economic matters, including among others, the Financial Markets Group of the London School of Economics.

This article is based on research published for Morgan Stanley Research on September 4, 2013. It is not an offer to buy or sell any security/instruments or to participate in a trading strategy. For important disclosures as of the date of the publication of the research, please refer to the original piece available here. For important current disclosures that pertain to Morgan Stanley, please refer to the disclosures regarding the issuer(s) that are the subject of this article on Morgan Stanley’s disclosure website. https://www.morganstanley.com/researchdisclosures.

Please note that materials that are referenced here are intended for informational use only, so please do not forward the content contained herein. If you should have a need to use/share the materials externally, please contact Charlie Anderson, Centre for Economic Policy Research. Additionally, MS and CEPR have provided their materials here either through agreement or as a courtesy. Therefore, MS and CEPR do not undertake to advise you of changes in the opinions or information set forth in these materials. You should note the date.

1 February 2013 BIS report “Mortgage insurance: market structure, underwriting cycle and policy implications”, http://www.bis.org/publ/joint30.pdf