Over the past few decades there has been great interest in taking formal finance to households around the world. These efforts have been especially focused on emerging economies. We are closer than ever to achieving this goal. Over a billion adults gained access to formal financial services through a recognised financial institution, or by accessing services over their mobile phones in the last five years alone. Not only have these households gained access to formal financial services, but there is also evidence that they use these services. Indeed, 53% of developing-country adults had active accounts in 2017, rising from 48% in 2014 (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2018). With the recent growth of low-cost technological solutions, international organisations and national governments are now targeting universal adult access to finance by 2020.

What comes next?

The need for access is universal, but the particular financial needs of individual households vary considerably over their lifecycle. At different points in their lifecycle, households save and borrow to finance education, housing, entrepreneurial opportunities, consumption in retirement, and to make payments for expected life events such as marriage, divorce, and bereavement. Moreover, needs vary across households on account of the specific idiosyncratic risks to which they are subject. To meet unexpected financial needs, households may sign up for insurance against health, employment, and other shocks.

The fast-growing academic field of household finance (Campbell 2006, Guiso and Sodini 2013) has studied how households do (and should) use financial instruments to attain their objectives. The field has rapidly expanded over the past few decades, painting a detailed picture of households’ circumstances, constraints, and behaviour using data primarily sourced from advanced economies (Badarinza et al. 2016). However, we know far less about households in emerging economies – an important gap with significant policy consequences.

Why study emerging economies?

Studying household finance in emerging economies is important for at least three reasons. First, emerging market households may be exceptional, for example with respect to the sets of risks that they are exposed to, and the unique constraints and circumstances that drive their behaviour. Second, from a welfare perspective, emerging economies have vast numbers of young households accessing financial markets for the first time. A growing body of evidence clearly demonstrates the long-lasting impacts of past experiences on economic behaviour (e.g. Malmendier and Nagel, 2011, Haliassos et al. 2016), so these first, defining encounters need to be managed carefully. Finally, broadening the scope of evidence will significantly bolster claims to external validity in the household finance literature. The body of facts that we currently rely on is incomplete, and possibly biased, without analysing the financial arrangements of the vast majority of households on the globe.

Household balance sheets in emerging economies

In a recent paper (Badarinza et al. 2018), we create harmonised measures of household assets and liabilities using representative micro-level survey data from six emerging economies, namely, China, India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Thailand, and South Africa—comprising 58% of the population of all emerging economies, and 45% of the global population. We contrast patterns in these data with those in advanced economy household balance sheets, namely, Australia, Germany, the UK, and the US.

We first document differences between the total levels of household wealth across emerging and advanced economies. To do so, we calculate the total wealth for each household by summing up their holdings of financial assets, durable goods (such as vehicles, livestock and farm equipment) and real estate (such as their main residence, holdings of farm land and second homes). We then map the percentiles of household wealth levels in emerging economies to the percentiles of the wealth distribution in advanced economies, adjusting for purchasing power.

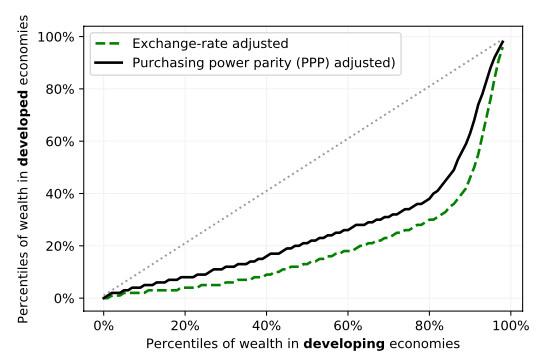

Figure 1 Comparing wealth distributions

(a) Aggregate

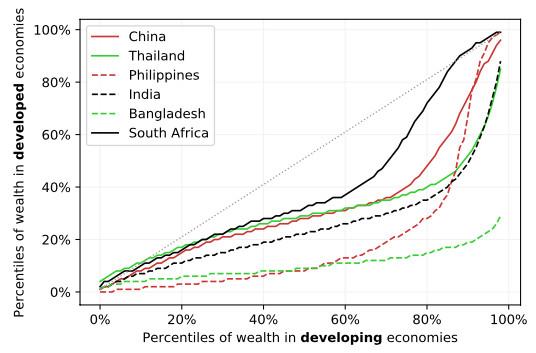

(b) By economies (PPP adjusted)

Figure 1 reveals that the very top and bottom of the wealth distributions in emerging economies have wealth levels that are similar to the top and bottom of the corresponding distributions in advanced economies, but substantial differences are visible in the middle of the respective wealth distributions. Adjusted for purchasing power, a wealth level at the 80th percentile of all emerging economy households places these households at the 40th percentile of the distribution of households in all advanced economies (Figure 1a). And across emerging economies, there are pronounced differences in the fractions of the population that map to different advanced economy wealth levels (Figure 1b).

These differences in the middle of the wealth distribution between advanced and emerging economies are notable. There are steep slopes in the region of the wealth distribution separating putative middle-class households from wealthy households in emerging economies. What drives this high degree of inequality in this region of the wealth distribution? One possibility is that they are in part driven by differences in the management of wealth between these households (e.g. Campbell et al. 2018).

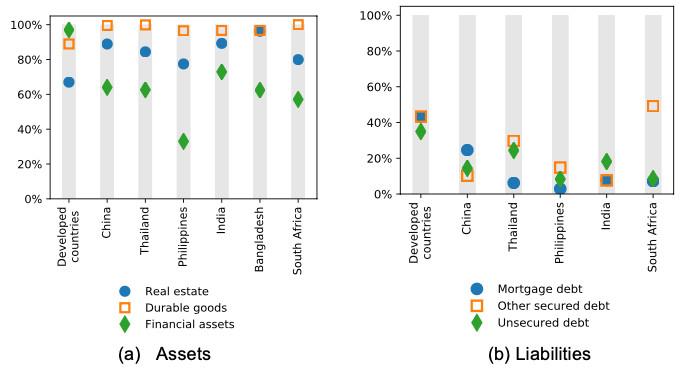

Figure 2 Participation rates

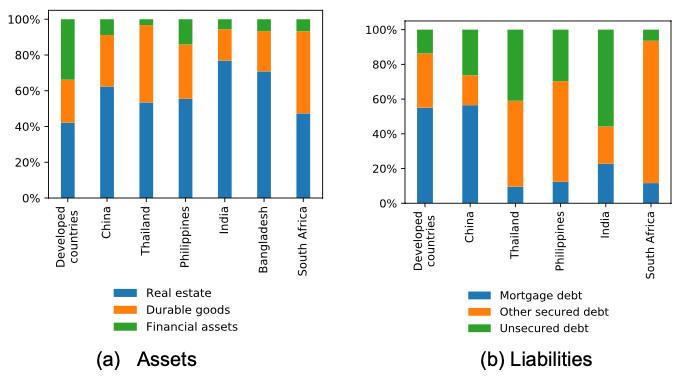

Figure 3 Allocation of household assets and liabilities

To investigate further, we document patterns of financial market participation and allocation across advanced and emerging economy households. Figure 2a shows that participation rates in financial assets are higher than those in physical assets such as real estate and durable goods in advanced economies, but this pattern is inverted for emerging economy households. Figure 3a looks at the allocation of assets, and shows, akin to the pattern of participation, that the largest part of household wealth in emerging economies is stored in physical assets, while an often-negligible fraction is in financial assets (mostly deposit accounts). Publicly traded equity and long-term defined-contribution retirement accounts are virtually absent.

Figure 2b shows the liabilities side of the balance sheet. In advanced economies, 40% of households participate in mortgages, secured, and unsecured credit from formal financial institutions. In contrast, the participation rates in liability markets are in single digits for emerging economies.

Figure 3b shows that large fractions of physical assets on the balance sheets in Figure 3a are not collateralised against debt, in contrast with advanced economies. Instead, emerging market households predominantly appear to use unsecured debt, often taken from informal providers, and often to fill short-term funding needs arising from health shocks, income loss, or property damage due to natural disasters.

Puzzlingly, we find that many of these patterns hold across age groups, and equally for relatively poor and relatively rich households. Even at the top of the wealth distribution, we find the same over-exposure to physical assets and unsecured debt.

What does all of this tell us? While there has been considerable progress on including emerging economy households in formal financial markets, there is still much work to be done to truly financialise household balance sheets. There are many differences between the management of wealth between emerging economy and advanced economy households, which we do not yet understand. We cannot simply stop at financial inclusion – we must move towards a deeper study of household finance in emerging economies.

The research and policy canvas

In our paper, we go on to summarise the nascent academic and policy literature in this area. Financialising household balance sheets in emerging economies is made difficult by both demand-side and supply-side constraints. While supply-side constraints are easing because of the rapid growth of financial technology, considerable challenges remain. Two big challenges are to get supply-side incentives in emerging economies right; and to properly account for the heterogeneity in demand across households (e.g. Agarwal et al. 2017).

Insurance and retirement accounts are virtually absent in emerging markets, and government-sponsored or mandated private schemes are often not widely available (Bloom et al. 2014). This is a particularly striking case in which the design of financial supply has not kept pace with the demand for customisation arising from households’ unique needs. These markets have also been plagued by inefficiencies and mis-selling (Halan et al. 2014), but there are significant efforts at improving their functioning by aligning the structure of incentives and the distribution of advice (Anagol et al. 2017).

Enabling mortgage market growth in emerging economies with innovative supply and robust regulatory design is a first-order concern. As migration, economic growth, and the desire for mobility generates changes to the pre-existing social structure (Lipset 2017), a well-functioning mortgage market can help to mitigate disruption. However, the expansion of mortgage markets in emerging countries is often hindered by the absence of robust legal and regulatory infrastructure (Warnock and Warnock 2008), in addition to the substantial interest rate and regulatory risk that can make these markets fragile (Campbell et al. 2015), and issues related to collateral verification and limited enforceability (Morris and Pandey 2009).

Households in emerging economies often source unsecured credit from informal providers such as money lenders. They can therefore become exposed to crippling interest payments and roll-over risk. Financial innovation has helped in this context, notably rotating credit and savings associations (ROSCAs) (Calomiris and Rajaraman 1998, Kapoor et al. 2011) and peer-to-peer lending (Lin et al.,2017). A continuing concern, however, is that the pace of innovation in new financial technology may outstrip regulatory capacity in emerging economies – meaning that distributional consequences to different groups of borrowers, inefficiencies, or even outright fraud are possible while regulators get up to speed.

On the demand side, formal financial savings are influenced by the extent of financial literacy, trust (e.g. Guiso et al. 2009), shame and embarrassment in reaching out for advice (Breza and Chandrasekhar, 2015), the irregular nature of income flows, and the volatility of household income (Reserve Bank of India 2016). Educating hundreds of millions of households that are rapidly entering financial markets is infeasible, and Campbell (2016), for instance, makes a strong case for robust consumer financial regulation in cases in which households lack the knowledge to manage their financial affairs effectively.

To better serve households that are newly included in financial markets, we propose an increase in (positive and normative) work in both development finance and household finance. A special focus needs to be made on understanding the intensive margin of newly participating households' decisions, i.e. observed and optimal allocation to particular assets and liabilities. We hope that there will be rapid growth in what is clearly an important field of study.

References

Agarwal S, S Alok, P Ghosh, S Ghosh, T Piskorski and A Seru (2017), “Banking the unbanked: What do 255 million new bank accounts reveal about financial access?”

Anagol S, S Cole and S Sarkar (2017), “Understanding the advice of commissions-motivated agents: Evidence from the Indian life insurance market”, Review of Economics and Statistics 99: 1–15

Badarinza C, V Balasubramaniam and T Ramadorai (2018), “The household finance landscape in emerging economies”, Working Paper.

Badarinza C, J Y Campbell and T Ramadorai (2016), “International comparative household finance”, Annual Review of Economics 8: 111–144.

Bloom D E, R McKinnon et al. (2014), “The design and implementation of pension systems in developing countries: Issues and options”, International Handbook on Ageing and Public Policy 108

Breza E and A G Chandrasekhar (2015), “Social networks, reputation and commitment: Evidence from a savings monitors experiment”, NBER Working Paper.

Calomiris, C W and I Rajaraman (1998), "The role of ROSCAs: lumpy durables or event insurance?", Journal of Development Economics 56(1): 207-216.

Campbell, J Y (2006), “Household finance”, Journal of Finance 61(4): 1553–1604.

Campbell J Y (2016), “Restoring rational choice: The challenge of consumer financial regulation”, American Economic Review 106: 1–30

Campbell J Y, T Ramadorai and B Ranish (2015), “The impact of regulation on mortgage risk: Evidence from India”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7: 71–102

Campbell J Y, T Ramadorai and B Ranish (2018), “Do the rich get richer in the stock market? Evidence from India”, American Economic Review: Insights (forthcoming)

Cecchetti, S and K Schoenholtz (2018), “Banking the masses: 2018 edition”, VoxEU.org, 26 June.

Guiso L, P Sapienza and L Zingales (2009), “Cultural biases in economic exchange?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124:1095–1131

Guiso L and P Sodini (2013), “Household finance: An emerging field”, in Handbook of the Economics of Finance 2: 1397–1532, Elsevier.

Kapoor M, A Schoar, P Rao and S Buteau (2011), “Chit funds as an innovative access to finance for low income households”, Review of Market Integration 3: 287–333

Haliassos M, T Jansson and Y Karabulut (2016), “Incompatible European partners? Cultural predispositions and household financial behaviour”, Management Science 63(11): 3780–3808.

Halan M, R Sane and S Thomas (2014), “The case of the missing billions: Estimating losses to customers due to mis-sold life insurance policies”, Journal of Economic Policy Reform 17: 285–302

Lin, X, X Li and Z Zheng (2017), “Evaluating borrower’s default risk in peer-to-peer lending: Evidence from a lending platform in China”, Applied Economics 49: 3538–3545

Lipset, S (2017), Revolution and counterrevolution: Change and persistence in social structures, Routledge

Malmendier, U and S Nagel (2011), “Depression babies: do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(1): 373–416.

Morris S, and A Pandey (2009), “Land markets in India: Distortions and issues”

Reserve Bank of India (2017), Report of the Household Finance Committee.

Warnock V C and F E Warnock (2008), “Markets and housing finance”, Journal of Housing Economics 17: 239–251