The ‘housing affordability crisis’ has been in the headlines in many parts of the world, and for a good reason. Among the 50 largest metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the US, half of all renter households spend more than 30% of their income on rent (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University 2018). They are rent burdened. Other common metrics to quantify the lack of affordability are average rent-to-income and house price-to-income ratios. All of these metrics have been rising in most major cities in the world. Housing affordability has been the leading challenge for local policymakers. Yet a coherent framework for analysing the various policy options is lacking.

A new framework

In a recent paper (Favilukis et al. 2019), we build a framework to evaluate four major housing policy tools – zoning changes, rent control, housing vouchers, and tax credits – that policymakers employ to tackle housing affordability issues. The framework is adapted from modern macroeconomics and finance. Each period, households that differ in age and labour productivity make choices about how much to consume, save, and work; whether to own or rent a house; the size of the house; and how large a mortgage to get if they own. Savings are invested in a government bond or in rental housing.

We introduce a spatial dimension in this macro model. The metropolitan area has two locations: the city centre where people work but only some households live (zone 1), and the suburbs/outer boroughs of the MSA (zone 2) from which households commute to work. Commuting has a time cost and a financial cost. Households can choose their location in each period. Households are risk averse and face labour income and mortality risk, which they cannot perfectly insure against. This market incompleteness is the key friction in the model. The government provides some insurance through the tax code, including for example unemployment insurance. However, local policymakers can affect the provision of social insurance by using affordable housing policies.

On the production side, developers decide how much housing to build in each location, using labour. Development is subject to zoning rules, which are particularly strict in the city centre. Developers are also subject to an affordable housing mandate, modelled after mandatory inclusionary housing: for every square foot of rental housing built, developers must set aside a percentage that rents at below-market rates. These affordable housing units are allocated by lottery and subject to an income qualification requirement. A household that gains access to an affordable housing unit is allowed to stay there without having to satisfy the income requirement again. The affordable housing mandate captures well the economic effects of rent control: landlords renting units at below-market rents to lower-income households who need to apply and qualify for such a unit.

Affordable housing mandates bring costs: housing supply reductions because developers face lower prices/rents; labour supply distortions because households may deliberately reduce labour supply in order to qualify for affordable housing; and housing misallocation. Misallocation takes several forms. When the income qualification threshold is set too high, middle-income households may win the lottery and push out households in greater need. Because they do not need to requalify after first entry, households who see their incomes rise are allowed to stay in their housing units. Households may live in the wrong zone because that’s where they won the housing lottery (a form of spatial misallocation). Finally, they may choose the wrong house size because the rent is discounted from the market rent.

But the model also captures a key benefit of affordable housing units: they act as insurance device against disposable income risk. When households fall on hard times, affordable units provide shelter at low rent, thereby improving housing stability. Because models in the affordable housing literature tend not to model household income risk, risk aversion, and market incompleteness, they miss this insurance benefit.

In sum, affordable housing policies have costs and benefits. Dialling the knobs of these policies up or down shifts the economy along the efficiency–equality trade-off curve. Since a policy usually benefits some households at the expense of others, we need to take a stance on how to aggregate individual households’ welfare. We choose a utilitarian social welfare criterion which weighs every household equally. But because poor households have higher marginal utility, there is more social benefit to helping them. How much more depends on the curvature of the utility function and how much residual risk they face given the social insurance programs already in place.

Main results

We calibrate the model to the New York MSA, and show that the model does a good job matching the observed income distribution and how it evolves as households age, average financial wealth levels and wealth inequality, the distribution of owned and rented house sizes, house price and rent levels, and home ownership rates. The model also captures current zoning policy and the share of affordable housing units currently in place in New York. With this ‘status quo’ as our baseline, we explore various policy counterfactuals.

The first main result is that reducing the misallocation of affordable housing units can lead to large welfare gains (a 3.6% gain in consumption equivalent units). Specifically, we lower the income qualification threshold for housing lottery winners, and force existing tenants to requalify every four years. By rotating out higher-income tenants and bringing in new low-income tenants, we improve access to the insurance provided by affordable housing units. We can do so without dramatically reducing housing stability. Of all the policies we analyse, reducing the misallocation of affordable housing units creates the largest welfare gain for society. This policy does not change the number of affordable housing units.

The second main policy experiment studies an expansion of the affordable housing mandate. Developers now must set aside a larger percentage of rentals at below-market rates than in the benchmark model. This policy is akin to an expansion of rent control since a larger fraction of the rental stock will be renting at below-market rates. A 50% expansion, which results in 30% rather than 20% of the rental stock being rented at a 50% discount to the market rent, creates a modest welfare gain of 0.66%. This gain is only about 1/6th as large as reducing the misallocation in the existing affordable housing stock, but comes at great expense to the developers in the form of billions of dollars in lost rents. The reason for the modest gain is that while the policy helps a larger number of needy households, it also creates more housing and labour supply distortions and more housing misallocation.

The third main experiment studies ‘upzoning’ – an increase in the amount of residential housing that may be built in the city centre (by 10%). This policy has the intended effect of lowering rents and house prices. But the welfare gain it creates is modest at 0.37%, or about half the gain from the expansion of rent control. In contrast to the previous policies, zoning is much less redistributive in nature. It benefits all age, income, and wealth groups (and even most homeowners who experience house price declines). But the policy fails to generate large welfare gains for the poor, which is where most of the bang for the buck lies in terms of welfare gains.

The fourth experiment expands housing vouchers, such as Section 8 vouchers. These are cash transfers earmarked for housing. The additional vouchers must be paid for with additional labour income taxes. Since the tax system is progressive, the highest-productivity households see their taxes rise the most. This results in a non-trivial reduction in labour supply and output. Despite the severe distortions, the voucher expansion is well targeted on the poor and creates a sizeable net welfare gain of 1.0%.

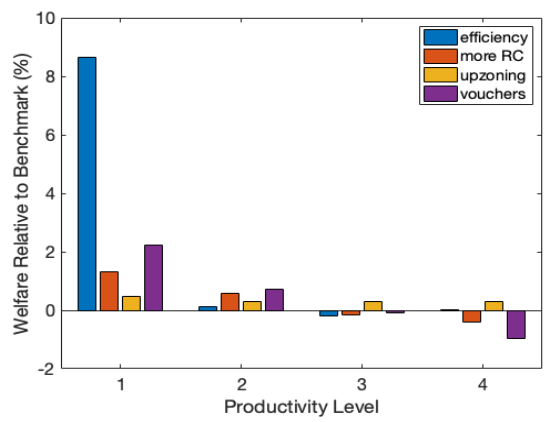

Figure 1 shows the welfare gains of the policies for households of different productivity levels. It clearly shows the redistributive nature of the policies that make affordable housing more efficient, that expand rent control, and that increase vouchers. The upzoning policy creates smaller, but more uniformly distributed benefits.

Figure 1

In the paper we also consider low-income housing tax credits, which we find to be fairly ineffective since they create modest rent reductions but are financed with distortionary taxation.

One more experiment worth mentioning is that moving all affordable housing units from the city centre to the rest of the MSA leads to a welfare gain, but only if it is accompanied by subsidies for transportation. The financial cost of commuting is an important factor for low-income households. Moving low-income rent-controlled tenants out of the city centre therefore makes them worse off unless they receive free transit. Only then do the improvements in the spatial allocation of labour result in a net welfare gain for society. The model ignores potential benefits for socioeconomic diversity at the neighbourhood level.

Policy implications

We need more efficiency in the affordable housing system with a renewed focus on helping the neediest. This need not require a massive expansion in the affordable housing stock; modest expansions can help in combination with reductions in misallocation. We also need to expand supply by relaxing zoning rules and other impediments to new construction, but cannot expect miracles form that approach alone.

References

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (2018), The State of the Nation’s Housing 2018.

Favilukis, J, P Mabille, and S Van Nieuwerburgh (2019), “Affordable Housing and City Welfare”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13758.