How should CEOs be paid? The simple answer is to give them shares in the firm, because this perfectly aligns them with shareholder value. But as Paul (1992) pointed out, an efficient contract pays the CEO based on her value added to the firm, not the value of the firm. Incentivising the CEO to exert effort – to add value – may involve a contract that’s more sensitive to firm value than simple equity.

The classic model from Innes (1990) solved this problem in a setting where the only measure of CEO effort is the firm’s output (for example, its cash flow). To incentivise effort, the contract should punish the CEO as much as possible for low output, and reward her as much as possible for high output. The first part is simple – the lowest the CEO can receive is zero, so the contract should pay her nothing if output is below a threshold (say, 100). Turning to the second part, the maximum reward the CEO can get is the entire firm’s output. So, the CEO gets zero if output is below 100, but her pay jumps to 100 – the entire firm output – once output reaches 100. If output rises to 110, she gets 110 since she receives the entire output.

But we don’t see such ‘all-or-nothing’ contracts in reality. Why not? Innes points out two reasons. First, if the CEO’s pay jumps from zero to 100 once output reaches 100, then she has incentives to manipulate output upwards. If cash flow is 99, she may even put her own money into the company to boost it to 100. Second, since shareholders’ payoff drops from 99 to zero once output reaches 100, they will have incentives to manipulate output downwards.

So, any realistic contract cannot involve shareholders’ payoff falling with output, which also means that the CEO’s pay can’t rise more than one-for-one with output. Innes shows that, under this restriction, the optimal contract takes a familiar form – the CEO receives equity and investors receive debt with a face value of 100.1 If cash flow is less than 100, the firm is bankrupt and investors get the entire cash flow. If cash flow exceeds 100, investors are repaid the face value of 100, and the CEO gets the rest.

How does this apply to a public company, where the ‘output’ that investors care about isn’t cash flow but stock price? Now, the contract is an option with a strike price of 100. The CEO receives nothing if the stock price is below 100 (i.e. the option is out-of-the-money), but gains one-for-one if the stock price exceeds 100 (i.e. the option is in-the-money).

Innes assumed that the stock price is the only measure of the CEO’s performance. But as explained earlier, multiple measures exist – financial metrics such as earnings and sales, and ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance) metrics such as emissions and safety. In practice, these metrics are incorporated by affecting the number of options that vest – a process known as performance-based vesting. If performance on these additional measures is poor, the CEO gets no options. The stronger performance is, the more options she receives, up to a maximum.

The use of performance-based vesting seems to be common sense. But it’s often based on ‘shooting from the hip’ rather than rigorous analysis, and there are very few theories that justify the use of performance-based vesting. In a forthcoming paper (Chaigneau et al. 2021), we analyse whether and under what conditions performance-based vesting is appropriate.

We point out that there are two dimensions that performance measures can affect: not only the number of vesting options, but also the strike price of these options. The number of vesting options affects the sensitivity of pay to the stock price (more options lead to a greater sensitivity), and the strike price affects the level of pay (a lower strike price leads to more pay).

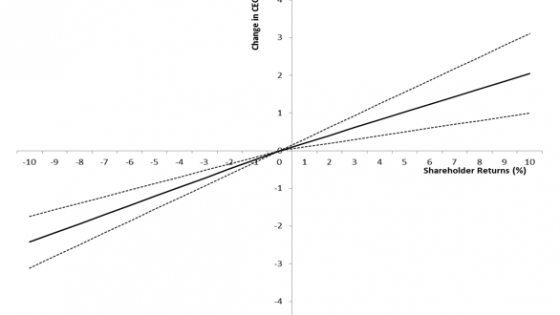

How a performance measure affects the contract depends on whether it affects the optimal sensitivity or level of pay. The sensitivity of pay should depend on how accurate the stock price is as a measure of the CEO’s effort. If the CEO has a limited effect on the stock price (e.g. she’s in a regulated industry), or if the stock price is volatile and affected by many factors other than the CEO’s effort, then CEO pay should not be sensitive to the stock price – the number of vesting options should be low. The level of pay should depend on how much effort we think the CEO has exerted. If the performance measure is good, the strike price should decrease so that the CEO is paid more.

This is not how things are done in practice. Most performance measures – such as earnings, sales, emissions, or safety – reflect the CEO’s effort, and so should change the strike price. Instead, they affect the number of vesting options. The number of vesting options should depend on performance measures that don’t actually measure CEO performance. Our analysis shows that vesting should depend on factors that affect the accuracy of the stock price, such as industry or market volatility, which have very little to do with the CEO. Any ‘performance measure’ that is truly an assessment of the CEO’s effort should affect the strike price. In reality, some measures may affect both the optimal level and sensitivity of pay. In these cases, the measures should affect both the strike price and the number of vesting options, rather than the ubiquitous practice of only affecting the latter.

In addition to options, our analysis applies to any other component of executive pay where the CEO receives zero if performance falls below a threshold. Other examples are bonuses (which are zero unless a performance threshold is hit), and performance shares (where the CEO receives no shares if performance is sufficiently poor). Most performance measures should affect the threshold required to trigger a payment, rather than how fast pay rises with performance if the threshold is hit.

For all of the above applications, you might wonder why good performance should reduce the threshold at all. Isn’t it easier to simply give the CEO a cash bonus for strong earnings, sales, or ESG performance? The answer is actually no. How much the level of pay should change depends not only on performance but also on the stock price. If performance is strong, but the stock price is sufficiently low, then it’s still optimal to pay the CEO nothing. This is achieved by reducing the threshold under good performance, as the CEO only benefits from the reduction if the stock price is sufficiently high.

Finally, some accounting systems penalise options with variable strike prices, as they need to be marked-to-market each quarter, thus affecting quarterly earnings. In contrast, companies don’t have to mark-to-market how performance affects the number of vesting options, so accounting systems cause distortions that may induce firms to adopt otherwise suboptimal practices. The ideal solution is for investors to reduce their focus on quarterly earnings, as argued by Edmans (2021). However, if this is unlikely, accounting systems should create a level playing field between different compensation structures, so that companies can choose based on their effectiveness rather than their accounting impact.

References

Chaigneau, P, A Edmans and D Gottlieb (2021), “How Should Performance Signals Affect Contracts?”, Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

Edmans, A (2021), “The dangers of sustainability metrics”, VoxEU.org, 11 February.

Innes, R D (1990), “Limited liability and incentive contracting with ex-ante action choices”, Journal of Economic Theory 52: 45–67.

Paul, J M (1992), “On the Efficiency of Stock-based Compensation”, Review of Financial Studies 5: 471–502.

Endnotes

1 In reality, the threshold will be different under a debt contract than an ‘all-or-nothing’ contract, but we keep the same threshold for ease of exposition.