Under what circumstances do democratic as opposed to authoritarian institutions emerge? Although a large literature has tackled this question (see Acemoglu et al. 2001, Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, Engerman and Sokoloff 2000), we still have an imperfect knowledge of how representative institutions originate and change. Political institutions are difficult to study not only because they are usually endogenous to other variables, such as inequality, culture, or geography, but also because institutional change is rare or may happen very gradually.

In a recent paper (Nikolova 2012), I argue that institutional change depends on labour market conditions: elites opt for liberal representative institutions when labour is scarce, and vice versa. I use a unique data set covering a period of relatively rapid change in representative institutions in the thirteen British American colonies from their very establishment to the American Revolution. In contrast to theories arguing that inequality is the primary determinant of the quality of political institutions (Boix 2003, Acemoglu and Robinson 2005), I show that liberal representative institutions may arise even in cases of high inequality, as the positive impact of labour scarcity outweighs the usual negative relationship between inequality and democracy. The relative fluidity of political institutions in this setting and time period also questions the validity of arguments linking institutions to historical persistence. In terms of implications for contemporary countries, the theory predicts that as autocratic regimes – such as China – face more binding labour constraints, democracy will be more likely to emerge.

Labour markets and political institutions: the South and the North

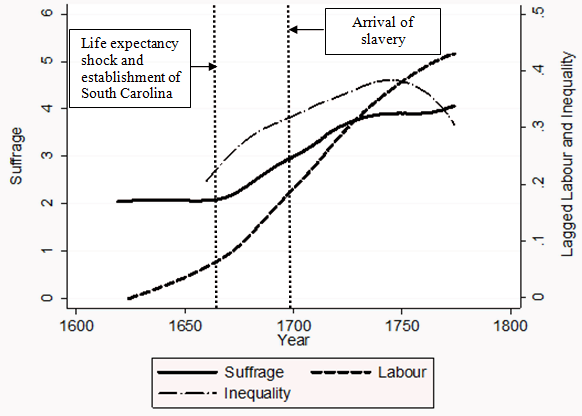

A first salient fact related to the early colonial period is that the American South – which had high land inequality and an unfavourable disease environment – actually enjoyed quite democratic political institutions, at least compared to the North (Figures 1 and 2). In the South, even settlers who were not free (such as indentured servants) or those without land or possessions could vote. The Southern landowners, who depended on the poor to produce labour-intensive export crops such as tobacco and rice, established liberal representative institutions to attract poor white migrants from Europe. The data show that suffrage conditions in the South responded quickly to the slavery shock in the late 1600s and early 1700s.1 Representative institutions became restrictive once rich planters had access to cheap labour and thus did not need to grant any political concessions to poor white voters.

Instead, the temperate climate of the North appealed to migrant families who wanted to settle permanently there, and population increase through reproduction was sufficient to satisfy labour demand. The region was mainly suitable for growing wheat, which could be effectively produced on small family farms. As a result, stricter franchise regulations (such as a religious restriction) were introduced to curb any additional immigration that could not be supported given the limited opportunities to grow export crops. Since the slavery shock had a limited impact on labour markets, political institutions remained largely unchanged.

Figure 1: Evolution of suffrage, inequality and labour markets in the South

Notes: This graph shows how suffrage restrictions, inequality and labour markets in the South evolved over time. The category 'South' includes Virginia, Maryland, South Carolina and North Carolina. The lines are obtained by locally weighted least squares smoothing over all colony-year observations. Suffrage is calculated by summing up dummies for different suffrage restrictions, such as land ownership, income and religion. Inequality is measured as the percentage of each colony’s landless population, where a higher value of percentage landless implies more inequality. Labour markets are measured as percentage black, where a higher value of percentage black implies a more satiated labour market.

Figure 2. Evolution of suffrage, inequality and labour in the north

Notes: This graph shows how suffrage restrictions, inequality, and labour markets in the North evolved over time. The category "North" includes Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maine, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware. See also notes to Figure 1.

Towards a new theory of political change

What explains these patterns? In the model used in my paper, the extensiveness of the suffrage is not only the usual determinant of equilibrium taxation and redistribution, but also a tool for profit maximising elites to credibly commit to wage and redistribution promises over the long run. While having the right to vote allows the poor to get the highest possible short-term redistribution, a representative assembly dominated by those with low incomes also serves to discipline any rich members wishing to implement measures aimed at reducing the long-term welfare of the poor. Therefore, a place with high wages and a wide suffrage is particularly attractive for workers with a below average income.

Conversely, the extensiveness of the suffrage can affect the welfare of the rich in two opposite ways. On one hand, strict voting restrictions enable the rich to control the assembly, which allows them to increase their incomes by passing laws aimed at depressing redistribution and the compensation paid to poor workers. This effect should be important when incomes are unequally distributed, as pro-poor transfers are particularly costly for the rich. On the other hand, a liberal suffrage attracts poor workers, which increases profits as long as the production function is upward sloping (as will be the case when scarce labour is the primary input in production). How elites weigh these two payoffs depends on whether labour markets are tight or easy and determines what type of institutions will ultimately emerge.

Were suffrage institutions used to attract labour?

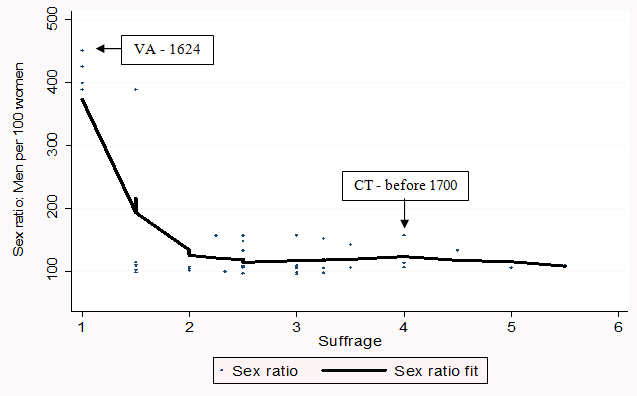

In addition to extensive historical evidence, there is also empirical evidence suggesting that southern representative institutions were indeed used as a tool to attract workers. Due to the hotter climates and the more virulent disease environment, the southern colonies at first had a very small female population, and therefore producing a steady labour supply or attracting whole families was difficult. Figure 3 shows that there is a negative correlation between suffrage and the sex ratio of men to women, which is consistent with elites using the suffrage to attract migrants in an environment which otherwise would have been difficult to populate. I also find that colonies with a higher life expectancy (and thus a higher expected labour supply) have less liberal representative institutions.

Figure 3. Sex ratio and suffrage

Conclusion

My analysis emphasises the importance of labour market structure in addition to inequality in explaining the evolution of political institutions in colonial British America. But just how relevant is the political experience of these colonies for explaining more recent institutional change? Female enfranchisement in Western Europe and the US coincided with the end of the First World War, which made male workers scarce (see Braun and Kvasnicka 2011). Similarly, countries with a labour shortage in particular occupations have point-based immigration schemes that grant citizenship and the associated political rights to qualified candidates. For instance, Canada and Australia have special programmes giving permanent residence to highly skilled immigrants. Therefore, the findings of my research provide a different angle to the debate in the literature on what pushes institutional change.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A Robinson (2001), "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation", American Economic Review, 91(5):1369-1401.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2005), Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, Cambridge University Press.

Acemoglu, Daron and James A Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail, Profile Books.

Boix, Carles (2003), Democracy and Redistribution, Cambridge University Press.

Braun, Sebastian and Michael Kvasnicka (2011), "Men, Women, and the Ballot. Gender Imbalances and Suffrage Extensions in US States", Kiel Working Papers 1625.

Engerman, Stanley and Kenneth Sokoloff (2000), "History Lessons: Institutions, Factor Endowments, and Paths of Development in the New World", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14:217-232.

Nikolova, Elena (2012), "Labour Markets and Representative Institutions: Evidence from Colonial British America", Working Paper.

1 The slavery shock in the south was preceded by two less intense labour market shocks, which took place in the 1670s. First, rising life expectancy among the white settlers increased the supply of available workers. Second, the settlement of South Carolina by former Caribbean planters who also brought some slaves with them made slaves more readily available (albeit not as extensively as following the later slavery shock).