Financial markets have made a dramatic leap in prominence throughout the world in recent decades. This is reflected not only in the growing size of the financial sector and its share of national income, but also in the fact that more and more individuals are engaged in the trading of stocks, either directly or via their pension savings. This trend has become even more pronounced during the COVID-19 lockdowns, with people staying at home with no sporting events to watch or bet on. Equity trading at Fidelity, for example, increased by 97% in the third quarter of 2020 from the previous year. This means that more and more people are participating in an activity that is centered on material gains, involves continued consideration of risk taking and risk mitigation, and often evokes strong notions of winners and losers. The economic benefits and risks of financial activity are widely discussed (e.g. Cornelli et al. 2020, Delle Monache et al. 2020, Furceri et al. 2019). In a new study we explore the political implications.

Many thinkers – from Montesquieu and Adam Smith to Marx, Schumpeter, and Albert Hirschman – have recognised the possible social and political repercussions of market activity. However, there is little agreement, and even less systematic evidence, about the nature and direction of the effects. Whereas some attribute to markets’ positive influences, nurturing frugality, moderation, wisdom, order, and responsibility (Montesquieu 1748, McCloskey 2006), others argue that markets commodify social relations, and make people egoistic and instrumental in their treatment of others (Marx and Engels 1848, Polanyi 1957, Sandel 2012).

Similarly, financial activity may affect political views. Recall President George W. Bush's push to "privatise social security''. Some of his supporters argued that broadening the share of the population who have a stake in the stock market would also lead to the expansion of the ideological Right's constituency. Yet the notion that exposure to markets – and in particular, financial markets – affects individuals' social-economic values and policy preferences remains largely speculative.

The main challenge to understanding the impact of financial activity on individual preferences is that such activity is naturally associated with a host of other personal, social, and political factors. For example, people with higher incomes or with greater trust in free markets may be more likely to participate in financial markets. To overcome these challenges, we conducted a field experiment, the results of which are reported in a new study (Margalit and Shayo 2020). The experiment was carried out with a national sample of 2,700 adult residents of England, 60% of whom had never invested in the stock market before. We randomly assigned 1,560 of them to receive substantial monetary sums (£50) that they could repeatedly invest in financial assets over a six-week period. In the weeks before and after the study, we also tracked participants' social and political attitudes as part of a separate study.

Beyond the main treatment group – which traded in real stocks such as Apple, Rolls Royce, and Siemens – we included a control group and two more asset treatments. These additional treatments varied from the main one in (a) whether the investments were in real or ‘fantasy’ money (i.e. did not involve actual monetary stakes), and (b) whether the investments were in company stocks, or rather in assets unrelated to the local economy – specifically assets indexed to the performance of sports teams in the US. These treatments were designed to help distinguish between different channels of influence. The sports treatment in particular replicated all the features of the trading environment (which could generate, say, excitement or risk taking), except that it did not expose participants to actual stocks.

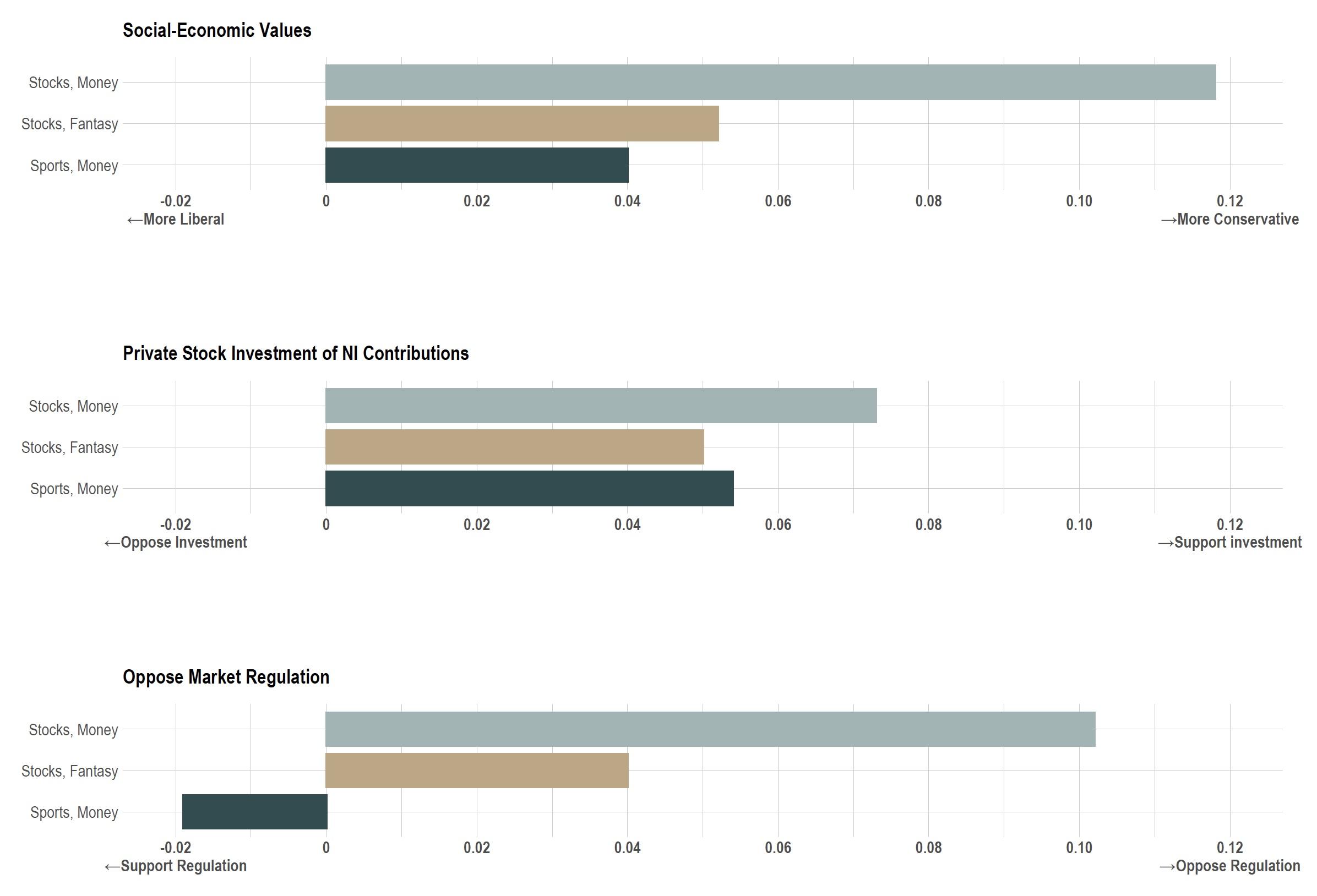

Figure 1

Note: The figures show the estimated treatment effect, after controlling for pre-treatment attitudes and characteristics.

We find that participants assigned to an asset treatment shifted rightward in their social-economic values, i.e. in their attitudes on issues such as economic fairness, inequality and redistribution, and the role of luck in economic success. This shift is illustrated in the top panel of Figure 1, which shows the effect of the three treatments on an index of social-economic values (attitudes on personal versus government responsibility, income inequality and redistribution, and the role of luck in economic success). Overall, exposure to an asset treatment led to a rightward shift in social-economic values equivalent to 9-12% of the gap between Labour and Conservative voters. The treatment effect largely persisted in a follow-up study a year later. These results complement recent findings from an experiment conducted in Israel showing that investing in the stock market moves people to the left on issues of peace negotiations and security (Jha and Shayo 2019).

What drives this effect? One possibility is that investment activity itself – with its focus on material gains, risk taking, winning and losing – triggers emotions and modes of reasoning that influence views on issues beyond traditional market activity. A second possibility is that rather than the investment activity itself, it is engagement with financial markets, and stocks of real-world companies, that influences social-economic values. Investors are exposed to broader aspects of the economy and the workings of markets, including the impact of changes in interest rates, the influence of political events on prices, and the consequences of market regulation. In turn, this may foster a sense of familiarity with, and greater trust in financial markets.

Our results support the second possibility. As seen in Figure 1, the treatment effect on social-economic values is much more pronounced among those assigned to trade in real company stocks with real money. Among subjects in this group, the effect was equivalent to 11-14% of the Labour–Conservative gap. By contrast, the effect was smaller (and statistically insignificant) when investments were in assets tied to the performance of baseball teams rather than in the stock market. We also cannot detect an effect among subjects in the fantasy treatment.

A rightward shift in social-economic values occurred among both left- and right-wing voters but was more pronounced among those on the left. We find little evidence that the change in attitudes was determined by how well participants' investments performed during the experimental period. The data also allow us to rule out that this attitudinal shift was driven by a deep change in subjects' tolerance of risk. In contrast we find that exposure to the market increased subjects' confidence in the ability of regular people to successfully invest in the market, as well as their own inclination to invest. This pro-market shift perhaps accounts for the broader rightward movement in social-economic values.

We also examine attitudes on a range of policy domains (second and third panel in Figure 1). Subjects exposed to the investment treatment, particularly those investing in the stock market with real monetary stakes, moved distinctly rightward in their views on policies related to market regulation and taxation. In contrast, no effect was registered with respect to government spending on unemployment assistance. Most notable was the effect on participants' views in the policy debate over the privatisation of pension savings. Compared to the control group, we find that, following the experimental treatment, subjects in the real stock treatment were about 7.5 percentage points more likely to support allowing citizens to invest their national insurance (NI) savings in the stock market. This represents a shift of almost 31% above the baseline rate of support.

Overall, these results suggest a rather inconspicuous effect of the growing financial sector on politics, an effect that goes beyond the visible and widely discussed channels of influence, such as large campaign contributions, lobbying activity, or the prominence of Goldman Sachs executives in the US government. By encouraging a pro-market social and political outlook, markets may engender a self-sustaining dynamic whereby their growing reach leads to wider support for their further expansion.

References

Cornelli, G, J Frost, L Gambacorta, P R Rau, R Wardrop and T Ziegler (2020), “Fintech and big tech credit markets around the world”, VoxEU.org, 20 November.

Delle Monache, D, I Petrella and F Venditti (2020), “COVID-19 and the stock market: Long-term valuations”, VoxEU.org, 24 August.

Furceri, D, P Loungani and J D Ostry (2019), “The aggregate and distributional effects of financial globalization”, VoxEU.org, 02 December.

Jha, S and M Shayo (2019), “Valuing Peace: The Effects of Financial Market Exposure on Votes and Political Attitudes”, Econometrica 87(5): 1561–88.

Margalit, Y and M Shayo (2020), "How Markets Shape Values and Political Preferences: A Field Experiment", American Journal of Political Science.

Marx, K and F Engels (1848), Manifesto of the Communist Party, 2013 ed., Simon & Schuster.

McCloskey, D N (2006), The Bourgeois Virtues, University of Chicago Press Economics Books.

Montesquieu, C L S (1748), The Spirit of the Laws, 1989 edition, Cambridge University Press.

Polanyi, K (1957), The Great Transformation, Vol. 5, Beacon Press.

Sandel, M J (2012), What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, Macmillan.