Worries about recession are rising, including in major advanced economies such as Germany and the US (Fatas 2019, Frankel 2018). There are also concerns that central banks may not have the tools to help economies avert downturns or moderate their impact. Policy interest rates remain near or even below zero in many economies despite years of expansion since the Global Crisis – limiting the room to cut rates – and whether unconventional monetary policies will be able to help much remains a matter of debate (Summers and Stansbury 2019). Policymakers in emerging markets are concerned about the spillovers from another round of easing in the major advanced economies.

In its latest report, the IMF’s Independent Evaluation Office – which operates at arm’s length from IMF management and the Executive Board – assessed the value provided by the IMF in its advice on unconventional monetary policies over the past decade. The report also puts forward recommendations for how the IMF could do better in its future advice on monetary policy issues that seem particularly relevant in view of recent stresses (Independent Evaluation Office 2019).

IMF corporate view

The IMF quickly developed a three-part ‘corporate view’ on unconventional monetary policies.

- First, the IMF viewed unconventional monetary policies as essential to recovery in the major advanced economies and provided steadfast support for the use of these policies (Lagarde 2013). After these economies turned towards fiscal consolidation in 2010 – a move the IMF supported – the Fund underlined that supporting aggregate demand through monetary easing was all the more important. The Fund urged the ECB and the Bank of Japan towards more aggressive easing of monetary policies (Ball 2019).

- Second, the Fund advised that any risks to financial stability arising from unconventional monetary policies were better addressed through macroprudential policies rather than by backing away from accommodative monetary policies.

- Third, the Fund assessed unconventional monetary policies to be, on balance, good for other countries as well by contributing to the health of the global economy. It did, however, recognise – and take steps to address – the challenges posed to others, particularly emerging markets, that could be impacted by easy global liquidity and volatile market conditions.

In the assessment of the Independent Evaluation Office, the IMF deserves credit for quickly developing this corporate view in the face of a very uncertain environment and articulating it clearly. The Fund also deserves credit for being at the centre of efforts to develop a macroprudential toolkit that countries could use to manage financial stability risks, including those from unconventional monetary policies. These efforts were recently summarised in Alter et al. (2019). The Fund monitored financial stability risks carefully and voiced concerns about potential danger points, such as overheating in real estate markets in some economies and the build-up in corporate debt in some others (Turner 2019).

The Fund also mounted a vigorous effort to help emerging markets through analytic work aimed at understanding better financial spillovers. This was done through new products such as Spillover Reports, by being more open to the use of capital controls – albeit under quite carefully circumscribed conditions – to deal with the volatility of capital flows, and by developing new precautionary credit lines that were used by a few countries – Colombia, Mexico and Poland.

Room for improvement

While recognising achievements, the report also identified limitations in IMF advice.

- First, the IMF could have done more to assess evidence on the effectiveness of unconventional monetary policies. The IMF’s initial support for these policies had to be based, by necessity, on the judgment of its management and senior staff rather than on evidence. But having put its weight behind these policies, the Fund could have done more to see if the policies were working as advertised in closing output gaps and bringing inflation rates back to their targets.

- A more robust investigation into the efficacy of unconventional monetary policies could have, in turn, improved Fund advice on the appropriate mix between monetary and fiscal policies. Our report concludes that the Fund should have been less willing to support the quick pivot from fiscal stimulus to consolidation in 2010. Greater sustained support from fiscal policies would have eased the burden on monetary policies and likely generated fewer challenges for other countries, a point recently also made by Grenville (2019). To be fair, the Fund did modulate its position on the policy mix over time, advocating that fiscal adjustment where needed should be growth-friendly and urging countries with fiscal space to use it.

- Third, the IMF could have done more to be of help to smaller advanced economies that were faced with challenging circumstances. The Fund had not anticipated the toolkit these economies would need as they hit the zero lower bound, leaving these countries to innovate on their own (Honohan 2019). For example, Denmark moved to negative policy interest rates in 2012, after intensive internal brainstorming at the central bank and some consultations with sources other than the IMF. Not until nearly five years later did the Fund issue its own cautious view on negative interest rates.

- Fourth, the IMF’s attempts to help emerging markets, while vigorous, left many policymakers unsatisfied. The Spillover Reports produced few analytic breakthroughs in understanding financial spillovers and did not influence policy advice, and as a result they were discontinued (Klein 2019). The openness to capital controls – while welcomed as a sign of a less doctrinaire IMF – has not gone far enough for those who would like to use them pre-emptively (ASEAN 2019), while others worry that the Fund has given open blessing to such controls.

Raising the IMF’s monetary policy game

What can be done to raise the value and influence of IMF advice on monetary policy at a time when it may again be called up? The report found that the Fund’s in-house expertise and resources devoted to monetary policy issues over the past decade were spread quite thin as the Fund increased its attention to new priorities, such as analysis of financial markets and labour markets (including issues of jobs, inequality and gender), within a limited budget envelope.

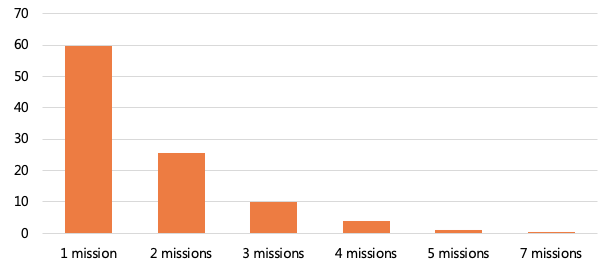

Figure 1 Participation by IMF staff in Article IV missions (by number of missions, in percent)

Frequent turnover among IMF country teams – particularly at the top (‘mission chiefs’ in the IMF’s terminology) – also came in the way of building the country understanding and relationships needed to provide persuasive cutting-edge advice to central banks. For example, Japan had seven IMF mission chiefs over the decade. Indeed, in every country covered in our report, the average stint of mission chiefs fell short of IMF management’s own goal. Figure 1 shows the turnover among IMF country teams. Sixty percent of IMF staff only go on one mission to a country before they are rotated off to other assignments – only about 15% go on three or more missions.

The report’s main recommendation is thus that the IMF should build up its expertise on monetary policy issues. It urges forming a small core group of experts to keep abreast of – and ideally even shape to some extent – thinking on major monetary policy issues and leverage their expertise to assist country teams who are giving advice to central banks facing novel or difficult challenges. In parallel, longer tenure of staff on country teams, which the IMF’s Executive Board has long called for, would help to increase understanding of country circumstances and deepen relationships. The Fund should be able to add particular value in its areas of clear comparative advantage – broad cross-country experience, attention to cross-border transmission channels, and its remit to look at the macro policy framework as a whole.

Bolstering the IMF’s monetary policy capacity will help it to assess better the costs and benefits of alternative unconventional monetary policies and what role monetary instruments should play together with macroprudential policies in staving off financial stability risks that might arise from unconventional monetary policies. The IMF’s policy positions on these topics need to be refreshed in light of the newer evidence (e.g., Eggertson and Summers 2019 on the effectiveness of negative interest rates). Other recommendations in the report address how the IMF can be of greater help to emerging market economies, such as re-energising the work on financial spillovers and policies for dealing with volatile capital flows.

The report’s recommendations were broadly endorsed by the IMF’s Executive Board, and the Fund’s management is now drawing up a plan on how to implement them. Encouragingly, some steps have already been set in motion, such as the setting up of a new unit to tackle cutting-edge monetary policy issues (Jeffery 2019). Clearly, it is neither needed nor feasible for the IMF to replicate the expertise that exists at central banks. But given its pre-eminent role in the international monetary system, and its role in validation and advising policy actions of its member countries, the IMF needs to be closer to the engine than to the caboose in helping keep monetary policies on the right track over the coming decade.

References

Alter, A, G Gelos, H Kang, M Narita and E Nier (2019), “Unveiling the effects of macroprudential policies: The IMF’s new iMaPP database”, VoxEU.org, 3 April.

Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) (2019) “Capital account safeguard measures in the ASEAN context”, ASEAN working committee on capital account liberalisation.

Ball, L (2019), “IMF advice on unconventional monetary policies to major advanced economies,” Independent Evaluation Office background paper BP/19-01/01.

Eggerston, G and L Summers (2019), “Negative interest rate policy and the bank lending channel”, VoxEU.org, 24 January.

Fatas, A (2019), “The 2020 (US) recession”, VoxEU.org, 14 March.

Frankel, J (2018), “The next recession will be a bad one”, VoxEU.org, 12 October.

Grenville, S (2019). “After Lagarde, IMF must learn from its mistakes,” The Australian, 19 August.

Honohan, P (2019), “IMF advice to Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden and the Czech Republic”, Independent Evaluation Office Background Paper No. BP/19-01/02.

Independent Evaluation Office (2019), “IMF advice on unconventional monetary policies”, evaluation report.

Jeffery, C (2019), “IMF sets up new monetary policy modelling unit”, Central Banking, 12 August.

Klein, M (2019), “IMF spillover analysis”, Independent Evaluation Office background paper BP/19-01/06.

Lagarde, C (2013), “The global calculus of unconventional monetary policies”, speech at Jackson Hole, 23 August.

Summers, L and A Stansbury (2019), “Whither central banking?”, Project Syndicate, 23 August.

Turner, P (2019), “Unconventional monetary policies and risks to financial stability”, Independent Evaluation Office background paper BP/19-01/05.