Editor’s note: This is an update of a column first published in April 2011.

In 2018, the US trade deficit with China in goods surged to $420 billion. The huge trade deficit triggered the on-going US-China trade war. In order to pursue so-called fair trade, the Trump administration has imposed a punitive 25% tariff on $250 billion’s worth of Chinese goods. Since the start of the trade war, the Chinese yuan has been depreciating against the US dollar. Alleging that the Chinese government used depreciation as a trade-war weapon, the Trump administration has designated China a ‘currency manipulator’.

There has been a consensus among economists that conventional trade statistics greatly exaggerate the US trade deficit with China (Johnson and Noguera 2012, OECD and WTO 2013, Koopman, Wang and Wei 2014). Xing and Detert (2010) use the iPhone 3G as a case and explain how the US trade deficit with China was inflated and why value-added should be used to assess the bilateral trade balance.

Since the 2007 release of the first-generation iPhone, China has been the exclusive base for iPhone assembly. With the launch of the iPhone X, the iPhone has evolved into a luxury high-tech gadget. In this column, I use the iPhone X as a case to discuss three questions. (1) Have the Chinese firms involved in the iPhone production moved up in the value-chain ladder? (2) Does the iPhone remain a significant source of the trade imbalance between the US and China? (3) Could the yuan depreciation hedge the risk of Trump’s tariffs?

Moving up the iPhone value chain

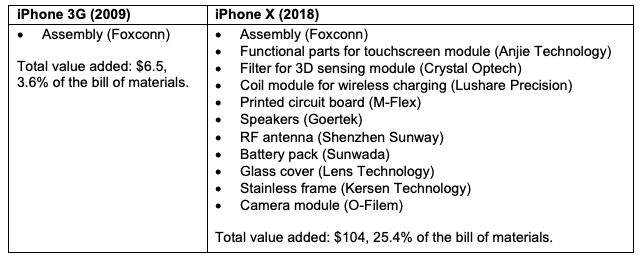

For an understanding of Chinese firms’ upward progress in the iPhone value chain, I examine the iPhone teardown data to assess Chinese-firm involvement in the production of the iPhone X. The teardown data identifies 10 domestic Chinese companies involved in iPhone X production. Their tasks go beyond simple assembly to include roles in relatively sophisticated segments. Table 1 lists the tasks performed by Chinese firms for the iPhone X in comparison with that for the iPhone 3G.

Table 1 Tasks performed by Chinese firms in iPhone 3G and iPhone X production

Source: Xing (2019).

For instance, Sunwada, a leading Chinese battery maker, supplies the battery pack of the iPhone X, and Chinese company Dongshan Precision supplies the printed circuit boards for the iPhone X through its acquired American company M-Flex. The involvement of those Chinese firms, though restricted to non-core technology segments of the iPhone X value chain, indicates that the Chinese mobile phone industry as a whole has moved to an upper rung in the iPhone value-chain ladder.

The bill of materials of the iPhone X is estimated at $409.25, of which the Chinese firms jointly contribute $104, about 25.4%. Chinese value-added in the iPhone X is dramatically higher than the $6.5 captured in the iPhone 3G. The retail price of the iPhone X is $1,000; the Chinese firms together gain 10.4% of the total value added of every iPhone X sold on the global market.

Figure 1 compares the Chinese value-added of the iPhone X with that of the iPhone 3G. It clearly demonstrates that the Chinese value-added embedded in iPhones increased substantially from the first generation to the iPhone X.

Figure 1 Chinese value-added embedded in the iPhone 3G and iPhone X

Source: Xing (2019).

The iPhone remains a significant source of the Sino-US trade imbalance

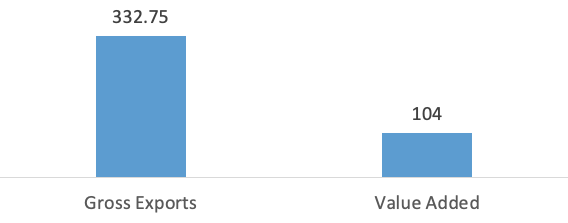

To date, trade statistics are still compiled using the gross value of exports, implicitly assuming that all gross value is generated by the exporting nation. According to that principle, whenever China ships one iPhone X to the US, the current system of trade statistics calculates it as a $409.25 export to the US.

The teardown data reveals that the total value of the parts imported from the US for assembly of the iPhone X is $76.5. Hence, importing one iPhone X from China generates a $332.75 ($409.25–$76.5) trade deficit for the US. That is the conventional approach to calculating bilateral trade balances.

However, Korea, Japan, and other countries are also involved in the production of the iPhone X and supply more than 45% of the parts and components. In other words, the $332.75 consists of not only value-added originating in China but also that contributed by Korea, Japan, and other non-US countries. It should be considered as a trade deficit between the US and all other countries involved in manufacturing the iPhone X, not just China.

In terms of value-added, the US deficit with China for the import of one iPhone X is only $104, less than one-third of the figure based on gross value (Figure 2). For every iPhone X imported by the US, current trade statistics mistakenly add $228.75 to its trade deficit with China. In 2017, American consumers bought 42.2 million iPhones units (Finder 2019). Using that figure as a reference, the iPhone trade alone exaggerated US trade deficit with China in 2018 by $9.65 billion, about 2.3% of its total deficit with China.

Figure 2 US trade deficit with China for one imported iPhone X ($)

Source: Xing (2019).

The iPhone case unambiguously demonstrates that conventional trade statistics significantly inflate China’s trade imbalance with the US. The iPhone, a product of an iconic American company Apple, remains a significant source of the Sino-US trade imbalance. Reducing the US trade deficit with China requires not only fair trade but, more importantly, unbiased trade statistics consistent with value chain trade.

Hedging Trump’s tariffs by yuan depreciation: Mission impossible

Xing and Detert (2010) argue that, because of the foreign value-added embedded in the iPhone 3G, appreciation of the yuan would have little impact on iPhone exports to the US. The same logic applies to the depreciation of the yuan. The large portion of the foreign value-added embedded in the iPhone X greatly weakens the effectiveness of yuan depreciation in counterbalancing Trump’s tariffs.

When the Chinese yuan depreciates against the US dollar, only the $104 Chinese value-added of the iPhone X will be affected. The rest of the iPhone X’s production cost—$305.25, the sum of all parts and components imported for assembling the iPhone X—will remain constant and not be affected whatsoever.

However, if President Trump decides to levy a 25% tariff on the iPhone X, the tax base will be $409.25, i.e. the sum of both Chinese and foreign value-added. To offset the tariff burden due to the foreign value-added, the yuan should depreciate much more than 25%.

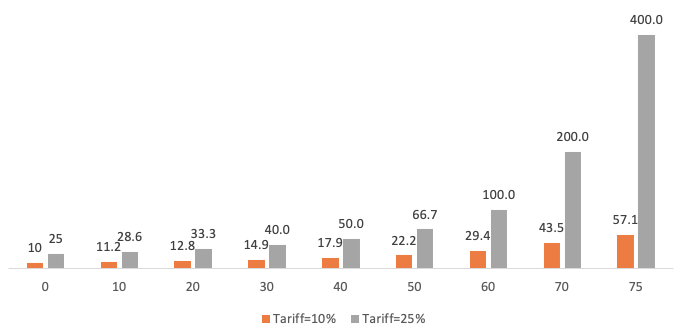

The level of yuan depreciation needed to completely offset the negative impact of a tariff can be calculated for any given foreign value-added. Figure 3 reports the computation results for two tariffs: 10% and 25%, where the horizontal axis denotes the percentage of foreign value-added embedded in Chinese exports.

Figure 3 Yuan depreciation required to offset US tariff effects (%)

Source: Xing (2019).

With a 10% tariff, an 11.2% depreciation of the yuan can counterbalance the tariff if foreign value added is 10%; for exports with 75% foreign value-added, the required depreciation surges to 57.1%.

If the tariff rises to 25%, the required depreciation increases substantially in all scenarios. The yuan would have to depreciate 28.6% in order to cancel the tariff’s negative impact if foreign value added is 10%, and 100% depreciation is required for Chinese exports with 60% of foreign value-added.

On average, foreign value-added accounts for 33.9% of Chinese exports to the US. This implies that a 43.4% depreciation of the yuan is required to completely cancel the negative impact of a 25% punitive tariff on all Chinese exports to the US, while an unthinkable 400% depreciation of the yuan is necessary to eliminate the negative impact of the same tariff levied on the iPhone X. The depreciation rates required to compensate for a 25% tariff are generally too high to be realised. It is ‘mission impossible’ to use yuan depreciation to hedge the risk of Trump’s tariffs.

Since conventional approaches cannot eliminate tariff burdens, for multinational enterprises using China to assemble products catering to the US market, one feasible option is to shift part of their value chains out of China. Apple has asked its major suppliers to evaluate the cost implications of shifting 15-30% of their production capacity from China to Southeast Asia (Li and Cheng 2019).

The trade war is reshaping China-centred value chains. The redeployment of the China-centred global value chains will permanently damage China’s export capacity and China will no longer play a central role in the global value chains targeting the US market.

Reference

Finder (2019), “iPhone sales statistics: Just how popular is Apple’s smartphone in the US?”, Finder.com.

Johnson, R C, and G Noguera (2012), “Accounting for intermediates: Production sharing and trade in value added”, Journal of International Economics 86: 224–236.

Koopman, R, Z Wang and S Wei (2014), “Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports”, American Economic Review 104(2): 459–94.

Li, K, and T Cheng (2019), “Apple weighs 15%-30% capacity shift out of China amid trade war”, Nikkei Asian Review, 19 June.

OECD and WTO (2013), “Trade in value-added: Concepts, methodologies and challenges”, Joint OECD-WTO Note.

Xing, Y (2019), “How the iPhone widens the US trade deficit with China: The case of the iPhone X”, GRIPS Discussion Papers 19-21.

Xing, Y, and N Detert (2010), “How the iPhone widens the US trade deficit with PRC”, ADB Institute Working Paper 257.