Ideas are fundamental to the production of any creative output, whether in the arts, sciences, or in business. However, because ideas are so elusive, little is known about how they are transmitted between people. Teachers, mentors, and role models provide influence in many ways (Rivkin et al. 2005, Rocko 2004, Chetty et al. 2014, Waldinger 2010). However, in creative professions it is possibly their creative or intellectual influence that matters most: how teachers shape a student’s skills and views of the craft, and in turn the nature of the work they go on to produce. Teachers or professional leaders with wide reach can even affect the direction in which entire fields move.

Academic researchers may recognise the potential for this influence, reflecting on how they themselves may have been shaped by where they did graduate work and the faculty who taught their courses or advised them.

On the one hand, instruction by subject matter experts is essential for transmitting basic principles and skills and for the ability to discern good from low-quality work. But it may also imbue students with tastes and methods of a teacher who is out of the mainstream or who does not meet contemporary standards. At the extreme, this influence may even cause bad ideas to propagate. Whether or not teachers and role models in creative fields leave an imprint on their students that shapes their future work is an empirical question.

In a new paper (Borowiecki 2022), I study this question in the context of Western music composition over five centuries. Examining a historically important cultural institution in a setting where composers’ musical lineage is well-documented allows the content of their work to be directly compared and its lasting value measured. I develop a novel approach to provide unique insights on how teachers influence the creative work of their students, how long this influence lasts, and what the consequences are for the students’ inventive output.

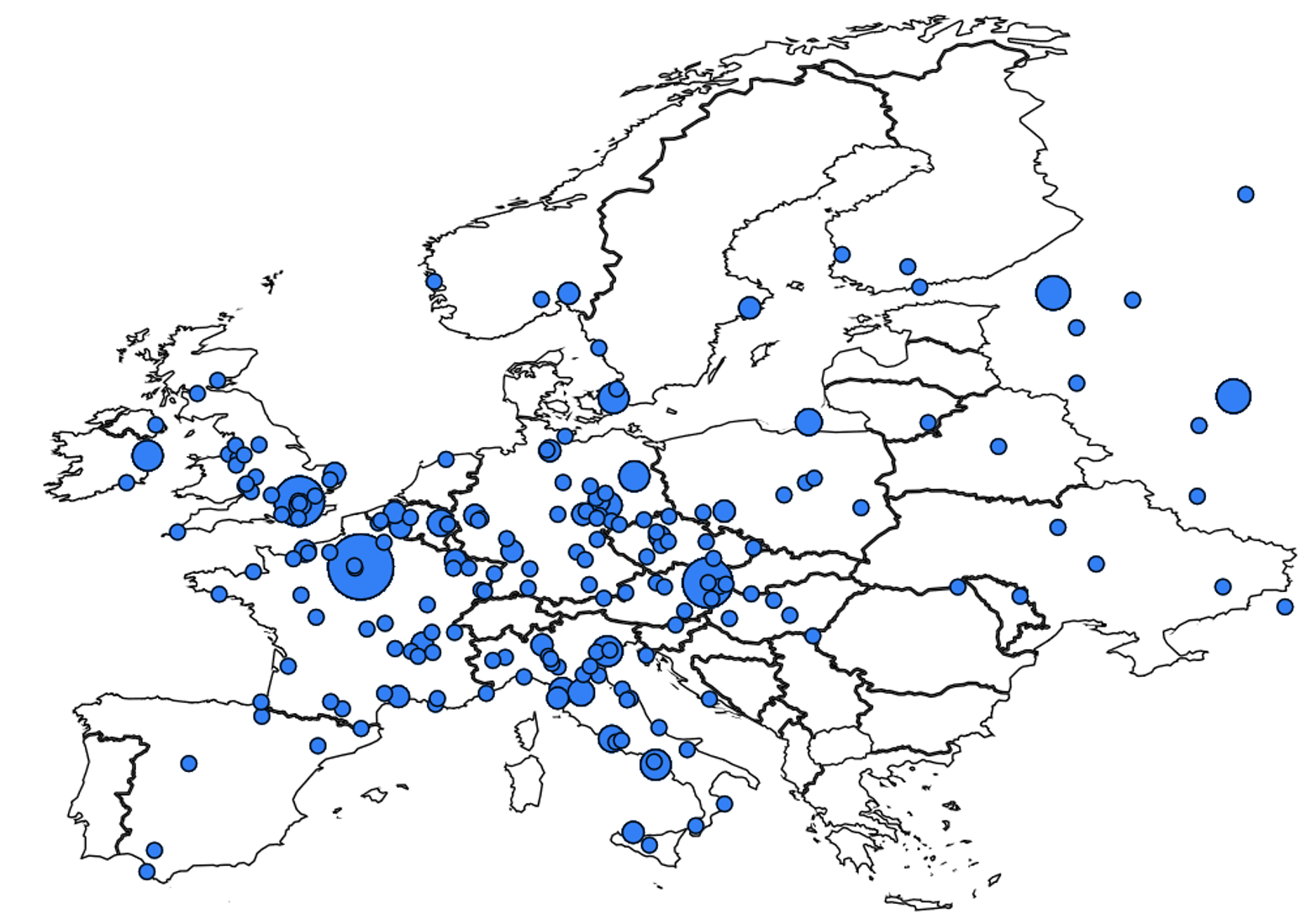

Figure 1 Map of composers by birth location in Europe

Notes: The map shows birth location for composers born in Europe and listed in Barlow and Morgenstern (1975, 1976). The data were collected by the authors (see Borowiecki 2022, Section 4 for details).

Using unique data capturing key attributes of a creative output for around 15,000 music compositions by hundreds of composers, I calculate similarity measures between pairs of composers (or across compositions) and confirm that students are more similar to their teachers than to other, unconnected, contemporaneous composers.

The influence is shown to persist throughout the next two to three generations in a composer’s musical lineage, as many students went on to become composition teachers themselves, but the effect subsequently starts to fade. I also confirm the results by comparing unconnected students who had a teacher in common – these students are more similar to each other than to other contemporaneous composers.

I then explore the consequences of the observed influence in an attempt to determine whether influence is a good thing. Does it cause only good ideas to persist, or bad ones too? My findings indicate that students who imitated to a greater degree a high-quality teacher were themselves more likely to become higher-quality composers. On the other hand, increased imitation of a low-quality teacher reduced students’ chances of success later in life. This underscores the importance of choosing the right role model.

It becomes clear that the ideas in circulation are not always good; indeed, some transmitted ideas and practices may be detrimental to the success of a young individual. This poses an additional challenge to the student, who may need to carefully filter out and identify best practices for herself. These observations carry particular weight considering the potentially long-term nature of influence experienced early in a person’s life or career.

The results have implications for our understanding of the production of creative or intellectual output, specifically around questions of where ideas come from; why certain ideas get produced as opposed to others, and by whom; and what the consequences might be. These questions are of general interest and also have significant market implications.

References

Borowiecki, K J (2022), “Good Reverberations? Teacher Influence in Music Composition since 1450”, Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman and J E Rocko (2014), “Measuring the Impacts of Teachers: Evaluating Bias in Teacher Value-Added Estimates”, American Economic Review 104(9): 2593–2632.

Lucas, R E (2008), “Ideas and Growth”, NBER Technical Report 14133.

Rivkin, S G, E A Hanushek and J F Kain (2005), “Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement”, Econometrica 73(2): 417–458.

Rocko, J E (2004), “The Impact of Individual Teachers on Student Achievement: Evidence from Panel Data”, American Economic Review 94(2): 247–252.

Waldinger, F (2010), “Quality Matters: The Expulsion of Professors and the Consequences for PhD Student Outcomes in Nazi Germany”, Journal of Political Economy 118(4): 787–831.