This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU Debate "The Economics of the Second World War: Eighty Years On"

Every aspect of WWII is discussed in a vast literature. Considering its diversity, explanations of why Germany lost the war are surprisingly predictable. It remains widely argued that the Nazis were beaten mostly by the Soviet Union’s powerful Red Army (Hastings 2005: 508, Kennedy 2013: 183).

From June 1941 to May 1945, German ‘power’ was supposedly engaged and destroyed by the Russians. At some points, more than two-thirds of German infantry were engaged against the Red Army. The famous battles of the Eastern Front, such as Stalingrad and Kursk, supposedly caused the Germans’ crippling losses. The upshot of this lopsided deployment was that most German soldiers died in the East. Fighting against the Americans and British, conversely, is often portrayed as a secondary concern (Roberts 2010: 573).

What’s wrong with a focus on battles?

This battle-centric view, like much history of WWII, is old-fashioned. Historians of strategy have moved away from seeing battles as determinative. Nolan (2017) has argued that attrition losses are more important than battle losses in explaining outcomes.

The battle-centric analysis implies that infantry deployment is the best way to analyse effort. Yet, human-power was rarely the key factor in deciding combat in WWII. Equipment and specialised training mattered more. Possessing and operating the largest stores of modern weapons, not only tanks and artillery but also aircraft and naval vessels, determined the course of battles and the war.

If we reframe the discussion of the war to look not only at what equipment was made but also at how it was destroyed, it emerges that the war was decided far from the land battlefield (O’Brien 2015). The most striking sign of this is how little war production went to the land war and how much went to the combined air-sea war. This was the case for all the powers except the USSR.

Germany

Normally, one thinks of the German Army (with the Waffen SS) as the dominant military arms of the Nazi state. This is a mistake. German ground forces received on average about one-third of German munitions output (O’Brien 2015, 19-33). Major ground weapons systems such as the famous Panzers were a small part, usually closer to 5% than 10%, of total output. Tanks were dwarfed by equipment for the Luftwaffe. Throughout the war, the building and arming of aircraft took up half of German munitions output or more. Beyond this, the supply of anti-aircraft artillery (flak) took up a growing percentage of German output—reaching over 10% in the last year of the war. Finally, the German Navy took a significant slice. Until Germany lost the war in the Atlantic in the summer of 1943, the German Navy often received more than 10% of munitions output (O’Brien 2015: 25).

Table 1 shows a snapshot of when German munitions output peaked (July 1944). It is striking how the air war dominated. Even with the Red Army and Anglo-American armies on their doorstep, production for the army remained a relatively small part of output.

Table 1 Germany, July 1944: Munitions production by type (% of total)

Source: USSBS (1946a: 145).

The German situation was replicated by the other advanced industrial economies. The US, UK, and Japan each spent more than Germany on the air-sea war, with at least 70% of munitions output devoted to air-sea weapons (O’Brien 2015: 33-66).

Japan

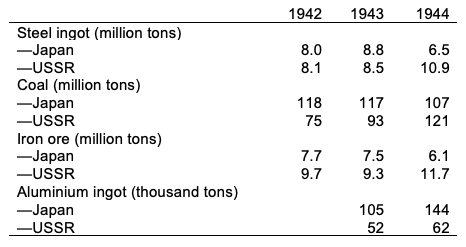

For Japan, an equipment-centric perspective suggests that that nation’s strength in the war has been overlooked. Histories of the war may give the impression that the war in the Pacific was a sideshow (Beevor 2012). Actually, Japan was at least an economic equal of the USSR from 1942 until the second half of 1944, with a superior economic base and no economic support from its allies.

Table 2 Japan and USSR, 1942-1944: Production of raw materials

Sources: USSBS (1946b: 112) for Japanese steel ingot production. For Soviet production see Ellis (1993: 274-276). Tons are metric.

The problem that Japan faced was one of priorities. The sea war required massive amounts of steel. Whereas the USSR used steel for tanks, the Japanese used an equivalent amount for naval vessels and merchant shipping. The difference was not one of economic strength but construction priority (O’Brien 2015: 59-65).

How Axis fighting power was destroyed

Given that air-sea weapons were so costly, what role did they play in beating the Axis? The answer shows why the air-sea war was so dominant. Instead of waiting to destroy Axis equipment on the traditional battlefield, Allied air-sea weaponry destroyed it en masse before it could ever be used in action, determining the result of every ‘battle’ long before it was fought. This destruction of equipment is best understood in three phases.

First, there is pre-production destruction, which prevented weapons from being built. This was done most efficiently to both Germany and Japan by depriving them of the ability to move raw materials. By 1942, both Germany and Japan had assembled large, resource-rich empires that had the ability to significantly increase weapons output. Though production increased up to early 1944, this increase was far below what was planned. In the case of German aircraft, for instance, output in the second half of 1943 was 10% below expectations because of Anglo-American bombing (O’Brien 2000: 104). Japanese inability to import bauxite and steel in 1944, abundant in the Dutch East Indies and China, led to even greater underproduction. By the second half of 1944, attacks on the movement of goods throughout the Japanese and German economies meant that the amount of war equipment each could build was far below potential (Mierzejewski 2007: 106-113).

The second phase is direct production destruction—destroying the facilities to make weapons in Germany and Japan. This was the great hope of inter-war airpower enthusiasts for the precise targeting of individual munitions factories (Meilinger 1997: 1-114). During the war, there was an expectation that attacking specific industries such as German ball-bearing production would cripple weapons output. The truth was that these attacks were not as effective as hoped for, as strategic bombing was not accurate enough to completely wipe out facilities (until 1944). That being said, the losses from bombing were greater than those arising in land battles.

The surprise is that land battles destroyed little equipment. German armour losses during the Battle of Kursk amounted to approximately 0.2% of annual output (and moreover was made up of mostly obsolete equipment) (O’Brien 2015: 310-311).

Finally, there were deployment losses. Getting weapons from the factory to the front was no easy feat. It normally required movement over hundreds or thousands of miles using shipping or rail lines that were vulnerable to attack. Aircraft had to be flown, often by inexperienced pilots, over the open ocean in or through difficult weather conditions.

By 1943, as Anglo-American aircraft deployment losses decreased, Axis losses skyrocketed. This was because of the stresses placed on their systems by Allied air-sea power. German and Japanese pilot training was cut back as both ran out of fuel; hastily constructed new factories were producing more aircraft with undiscovered flaws; maintenance facilities at the front were poorly supplied. This meant that the Axis were losing as many aircraft deploying to the front as in direct combat. At times, Japan’s losses outside combat were up to twice those lost fighting (O’Brien 2015: 405-7).

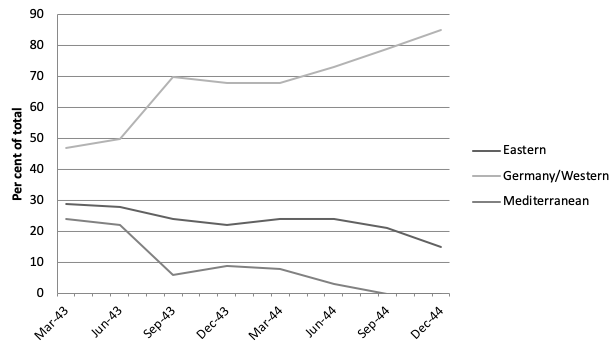

The air-sea war

The air-sea war determined the course of the land war. This was done in many ways, most obviously by denuding Axis ground forces of air support. In the summer of 1943, for instance, Germany had to deploy its fighter aircraft to three fronts—to the East, to the Mediterranean, and to air defence of the homeland. As homeland defence dominated, the battlefields were stripped of German fighters. The Army took second priority for the most valuable weaponry Germany was producing. It is no surprise that the German Army experienced catastrophic defeats from then on.

Figure 1 Germany, May 1943-November 1944: Fighter deployment (all types) by front (% of total)

Source: UK National Archives, London, Air Ministry Papers, 40/1207, “German Air Force First Line Strength during the European War, 1939-1945”.

Overall, by 1944 the Axis could deploy only a small fraction of their potential military capacity into combat—it was being destroyed in a multi-layered campaign long before it could be used against their enemies. This was the true battlefield of WWII, a massive air-sea super battlefield that stretched for thousands of miles not only of traditional front but of depth and height.

In the case of the European theatre, it covered an area from the East Coast of the USA to the aircraft factories in Eastern Germany, from the convoys moving goods around the top of Northern Norway to Murmansk to the massive airfields of North Africa and southern Italy. If it did not kill as many Germans directly as the Red Army, it was what allowed them to be killed—while destroying far more in the ways of valuable equipment.

Looking at the war this way allows us to reframe our understanding of what a battle was in WWII. Instead of battles being fixed on well-known pieces of earth, air-sea weaponry was constantly in action in battlefields thousands of miles long and many miles in depth—what should be called the Air-Sea Super Battlefield. Victory in this super-battlefield led to victory in the war.

References

Beevor, A (2012), The Second World War, New York: W&N.

Ellis, J (1993), The World War II databook, London: Aurum Press.

Hastings, M (2005), Armageddon: The battle for Germany 1944-45, London: MacMillan.

Kennedy, P (2013), Engineers of victory: The problem solvers who turned the tide in the Second World War, London: Penguin.

Meilinger, P (ed) (1997), The paths of heaven: The evolution of airpower theory, Maxwell, Alabama: Air University Press.

Mierzejewski, A C (2007), The collapse of the German war economy 1944-1945: Allied air power and the Germany national railway, Chapel Hill: UNC Press

Nolan, C (2017), The allure of battle: A history of how wars are won and lost, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Brien, P P (2000), “East versus West in the defeat of Nazi Germany”, Journal of Strategic Studies 23(2): 89-113.

O’Brien, P P (2015), How the war was won: Air-sea power and Allied victory in World War II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, A (2008), Masters and commanders: How four titans won the war in the west, London: Allen Lane.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) (1946a), Summary report (European war), Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) (1946b), Summary report (Pacific War), Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.