This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU Debate "The Economics of the Second World War: Eighty Years On"

What is the political legacy of WWII? One tradition has described war as the precondition for state formation and nation building (Tilly and Ardant 1975, Tilly 1985). Another emphasises the political and social disintegration that follows conflict, leading to heightened risk of further conflict and ‘conflict traps’ (Collier et al. 2003, Collier and Hoeffler 2004).

Two problems stand in the way of firm conclusions from macro-level studies. One is omitted variables that correlate with both the occurrence of conflict and the quality of institutions. Another is reverse causality between state capacity and conflict. These problems can be overcome by micro-level studies, which examine the effects of varying exposure to conflict on individuals in similar cultural and institutional conditions.

My research (Grosjean 2014) has found consistent patterns in how WWII shaped individual attitudes across Europe and Central Asia. A representative sample of respondents across 35 countries in 2010, 65 years after the end of the war, shows that a family history of wartime victimisation has systematically eroded political trust and the perceived legitimacy of institutions. Greater exposure to violence has also made people more likely to engage in political and social groups and collective action.

Data: The Life in Transition Survey

The Life in Transition Survey (LiTS) is a nationally representative survey in more than 30 countries of former Communist Europe and Central Asia, carried out by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank. Three waves have been collected since 2006. In 2010, the survey included a question on family and personal exposure to WWII, as well as to more recent conflicts for the countries that experienced a civil war since then. I focus here exclusively on WWII; in Grosjean (2014) I consider exposure to conflict more broadly.

The 2010 wave was also collected in five Western European comparison countries (France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, and Sweden). One thousand respondents were included in each country (1,500 in Ukraine and Russia), making the total number of observations more than 39,500. I exclude countries that were neutral during the war from the data, leaving a sample of 35,960 individuals.

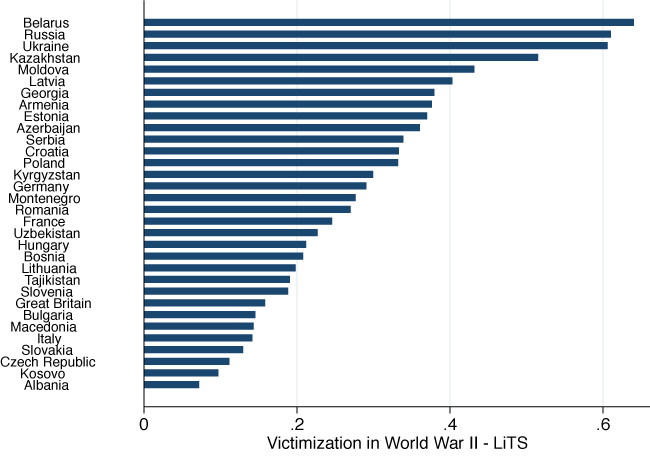

Asked whether they, their parents or their grandparents were physically injured or killed during WWII, nearly 30% of respondents answered yes (unweighted average). As Figure 1 shows, the incidence of victimisation ranges from more than 60% in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine to less than 10% in Albania and Kosovo.

Figure 1 The incidence of reported victimisation in WWII by country

Source: Grosjean (2014: 435).

Note: At the country level, the frequency of self-reported victimization is highly correlated with independent measures of war-related fatalities (Grosjean 2014: 436).

Which political and social norms are most critical for long-run stability and society? Trust in formal institutions has been found among the determinants of economic growth (Acemoglu 2005, Acemoglu et al. 2011, Besley and Persson 2009, 2010), market development (Greif 2012), economic liberalisation (Grosjean and Senik 2011), and post-conflict political recovery (Bigombe et al. 2000). Trust in others is also a factor in growth (Knack and Keefer 1997, Guiso et al., 2010), the functioning of markets (Fafchamps 2006), and institutional quality (Tabellini 2008, 2010). Participation in social groups and collective action is the focus of Puttnam (1995), and research on the social legacy of conflict has relied on similar measures of social capital (Bellows and Miguel 2009). Whether social capital is necessarily positive or negative for development is a point to which we will return.

The answers of the repondents to the LiTS allow us to measure the most relevant political and social norms.

- Trust in central institutions of the nation: the presidency, the government, and the parliament, scaled 1 (low) to 5 (high).

- Perceived fairness of the justice system: equal treatment in the courts and protection against the state, scaled 1 to 5.

- Trust in others (as against needing to be careful when dealing with others), scaled 1 to 5.

- Capacity for collective action: participation in demonstrations, strikes, or petitions.

- Participation in social groups: membership of religious, recreational, educational, labour, environmental, professional, charitable, or youth associations.

- Participation in politics: membership of a political party.

We then look at how respondents’ norms and preferences expressed in 2010 are related to family exposure to violence during WWII, which ended 65 years previously.

Confounding factors and reverse causality

In the first instance, I consider the relationship between the intensity of victimisation in WWII and political and social preferences across the whole sample. However, this relationship might depend on the outcome of the war for the nation. For example, trust in the state might be enhanced in countries that were victorious and weakened in those that were defeated. For some countries there was also a civil war, as in the Balkans. Therefore, I contrast the role played by victimisation among the Allies (Great Britain with the Allied governments in exile (today’s Czech Republic, Poland)) and the Soviet Union; the Axis and client states (Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Romania and Slovakia); and the remaining divided countries (Belarus, three Baltic states, France, Moldova, Serbia, Ukraine).

Second, the quality of institutions varies greatly across countries. For example, Great Britain and Bulgaria show similar wartime death rates but widely different institutions and cultural norms. This would influence individual answers about political trust or social capital, regardless of wartime experience. To speak to the legacy of wartime victimisation on political trust and social capital, it is essential to maintain constant the quality of formal institutions and cultural factors. For this reason, the analysis only compares individuals within the same neighbourhood (primary sampling unit) in the same country.

Third, there is the possibility of reverse causation: people may have suffered violence selectively, because of the level of their political trust or because they belonged to social groups or political parties. The fact that the war ended 65 years before the survey was conducted attenuates this selection concern. In 1939, only 8.4% of our respondents were alive; only 0.3% were 16 or older. The average respondent is 46 years old and thus reports their parents’ or grandparents’ victimisation, not their own. Systematic victimisation would be a problem only if the preferences that made people suffer wartime violence were inherited down the generations. Still, I control for respondents’ characteristics that could be correlated with political trust and social capital or family history of victimisation, such as age (and age squared), gender, ethnicity (proxied by mother tongue), education, working status, religion, and income. Essentially, I compare individuals not only from the same neighbourhood, but also with similar personal characteristics, who differed in family exposure to war violence.

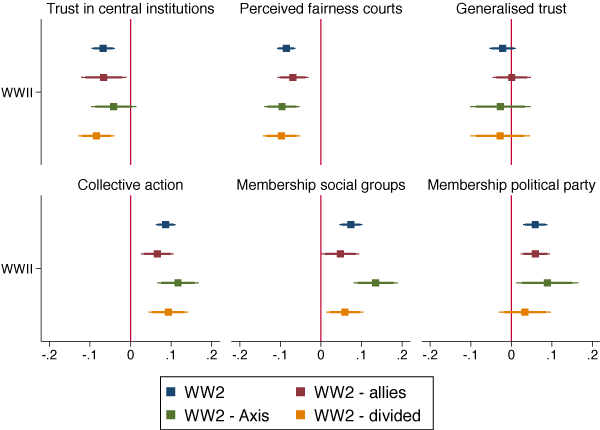

Figure 2 displays the results of OLS regressions of the indices of trust in institutions and of social capital on an index of wartime family victimisation. The regressions control for individual characteristics and neighbourhood fixed effects. As indicated in the figure’s legend, the first line uses the whole sample, the second only the sample of Allies, the third Axis countries only, and the last the sample of remaining divided countries.

Figure 2 Victimisation in WWII reduces political trust and spurs collective action

Source: Grosjean (2014).

Note: Each chart shows four coefficients on wartime victimization of a different dependent variable. The four coefficients, in order from top to bottom, are for the whole sample, Allies, Axis, and divided countries. Controls and fixed effects are described in the text. The dependent variables are standardised, so the coefficients are directly comparable. Standard errors are clustered at the country level. Horizontal bars correspond to 10% (thick line) and 5% (thin line) confidence intervals. When the confidence interval does not overlap with the vertical bar at zero, the coefficient is statistically significant at the 5% level.

On this basis, we reach four main findings:

- Wartime victimisation erodes trust in the state today.

- Wartime victimisation spurs involvement in collective action.

- For those whose families were victimised, membership of social groups marks even lower political and social trust.

- The effects on trust are stable down the generations.

Long-term effects of wartime victimisation

Wartime victimisation erodes trust in the state today.

Sixty-five years on, political trust is strongly and negatively affected by wartime victimisation, regardless of the war’s outcome for the country. (But the effect is only marginally significant in Axis countries.) The effect is similar on perceived fairness of the courts.

The magnitude of the results is quite large. Today, people whose families were victimised in the war are less trusting of the central state and of the courts by 0.07 and 0.08 standard deviations, compared with others with similar socioeconomic characteristics in the same locality. For trust in the central state this is nearly five time the effect of being unemployed. For trust in the courts, it is ten times.

By contrast, there is no strong effect on generalised trust – a puzzle to which we return below.

Wartime victimisation spurs involvement in collective action.

Today, people whose family was victimised in the war are more likely to engage in collective action by demonstrating, striking, or signing petitions, and they are more likely to join social groups and political parties. Again, the fate of the nation at the war’s end has no strong influence.

What is captured, exactly, by involvement in collective action and in social and political groups? The sociological literature is divided. Putnam (1995) sees it as promoting social cohesion. Bourdieu (1985) saw the opposite: social capital can be exploited in group rivalry, leading to social exclusion and political violence (see also Portes 1998). Recently the “dark side” of social capital has been unveiled by Satyanath et al. (2013): the density of civic associations in interwar Germany helped the advance of the Nazi Party to power. Similarly, victims of the 1990s Tajik civil war participate more in groups when they have less trust in other people and the state (Cassar et al. 2013a, b).

For those whose families were victimised in wartime, membership of social groups marks even lower political and social trust.

We find that the collective action spurred by war victimisation may be of a similarly dark nature. In families that were victimised, people who participate in groups today are those that place less trust in others and in politics (Grosjean 2014: 447-448).

This may solve the puzzle that our measure of generalized trust seems unaffected by wartime experience. Conflict may increase trust in friends and relatives, while reducing trust in strangers.

The effects on trust are stable down the generations.

Are the effects we observe driven by war survivors and the immediate post-war generation, and do they fade over time among younger people? Our data allow us to distinguish four different birth cohorts, separated by 1940, 1960, and 1980. I find that the overall legacy of war victimisation does not fade, showing only modest declines in some dimensions while increasing in others.1

Conclusion

Family victimisation in WWII has led, across the board, to a persistent decline in political and social trust. Far from fading over generations, some effects prevail among those born since 1980. Thus, wartime experience is among the complex mix of factors at work in the long-term decline of social and political trust across the Western world.

References

Acemoglu, D (2005), “Politics and economics in weak and strong states”, Journal of Monetary Economics 52(7): 1199–1226.

Acemoglu, D, Ticchi, D and Vindigni, A (2011), “Emergence and persistence of inefficient states”, Journal of the European Economic Association 9(2): 177–208.

Bellows, J and Miguel, E (2009), “War and local collective action in Sierra Leone”, Journal of Public Economics 93(11–12): 1144–1157.

Besley, T and Persson, T (2009), “The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation and politics”, American Economic Review 99(4): 1218–1244.

Besley, T and Persson, T (2010), “State capacity, conflict and development”, Econometrica 78(1): 1–34, 01.

Bigombe, B, Collier, P and Sambanis, N (2000), “Policies for building post-conflict peace”, Journal of African Economies 9(3): 323–348.

Bourdieu, P (1985), “The social space and the genesis of groups”, Social Science Information 24(2): 195–220.

Cassar, A, Grosjean, P and Whitt, S (2013a), “Legacies of violence: Trust and market development”, Journal of Economic Growth 18(3): 285–318.

Cassar, A, Grosjean, P and Whitt, S (2013b), “Social preferences of ex-combatants: Survey and experimental evidence from post-war Tajikistan,” in Wärneryd, K. (ed). The Economics of Conflict. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA

Collier, P, Elliot, L, Hegre, H, Hoeffler, A, Reynal-Querol, M and Sambanis, N (2003), Breaking the conflict trap: civil war and development policy, Oxford University Press and World Bank: Oxford and Washington DC

Collier, P and Hoeffler, A (2004), “Conflict”, in Lomborg, B. (ed). Global Crises, Global Solutions, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Fafchamps, M (2006), “Development and social capital,” Journal of Development Studies 42(7): 1180–1198.

Fafchamps, M (2006), “Development and social capital”, Journal of Development Studies 42(7): 1180–1198.

Greif, A (2012), “Coercion and exchange. How did markets evolve?” in Greif, A, Kiesling, L and Nye, J (eds), Essays in Economic History and Development, Stanford University.

Grosjean, P and Senik, C (2011), “Democracy, market liberalization and political and economic preferences”, Review of Economics and Statistics 93(1): 365–381.

Grosjean, P (2014), "Conflict and Social and Political Preferences: Evidence from World War II and Civil Conflict in 35 European Countries", Comparative Economic Studies 56(3): 424–451.

Guiso, L, Sapienza, P and Zingales, L (2010), “Civic capital as the missing link”, in Benhabib, J, Bisin, A and Jackson, M O (eds). Social Economics Handbook, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Knack, S and Keefer, P (1997), “Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(4): 1251–1288.

Portes, A (1998), “Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology”, Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24.

Portes, A (2010), Economic sociology: A systematic inquiry, Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Putnam, R D (1995), “Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital”, Journal of Democracy 6(1): 65–78.

Satyanath, S, Voigtlaender, N and Voth, H-J (2013), “Bowling for fascism: Social capital and the rise of the Nazi party in Weimar Germany, 1919–33”, NBER Working paper no. 19201, NBER: Cambridge.

Tabellini, G (2008), “The scope of cooperation: Norms and incentives”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3): 905–950.

Tabellini, G (2010), “Culture and institutions: Economic development in the regions of Europe”, Journal of the European Economic Association 6(2–3): 255–294.

Tilly, C (1985), “War making and state making as organized crime”, in Evans, P, Rueschemeyer, D and Skocpol, T (eds). Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, C and Ardant, G (1975), The formation of national states in Western Europe, Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Endnotes

[1] These results are not reported in Grosjean (2014). Details are available from the author upon request.