Despite changes in social norms and policy reforms over recent decades, gaps in hourly wages between similarly qualified women and men remain significant, ranging between 10% and 20% in most OECD countries (OECD 2018). The ongoing COVID-19 crisis has made the issue of addressing gender wage gaps even more pressing, as most of the increased household responsibilities fall to women, which may further reduce their earnings in the long term (Fabrizio et al. 2020, Queisser et al. 2020, Sun and Russell 2021).

In order to devise effective policies to narrow gender wage gaps, we first need to understand what their drivers are. In a new paper (Ciminelli et al. 2021), we source data on earnings, hours worked, and many other labour market and demographic characteristics for over 33 million individuals in 25 European countries to analyse the role of social norms and discrimination (‘sticky floors’) as well as the wage penalty related to childbirth (‘glass ceilings’).1

On average, women earn about 15% less per hour than men

A first look at the data confirms that gender wage gaps are significant. In the average country, women earn about 15% less per hour than similarly qualified men (Figure 1). This figure masks important differences across individual countries, with the gap between women and men ranging from below 10% in Hungary, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Turkey to over 20% in Estonia, Finland, Portugal, and the Slovak Republic.2

Figure 1 Differences in women’s hourly earnings relative to men, controlling for age, tenure, and education (%)

Note: The chart shows percent differences in average hourly earnings per hour worked of women relative to men with the same level of educational attainment, age, and tenure in 2014.

Source: Eurostat Structure of Earnings Survey and OECD calculations.

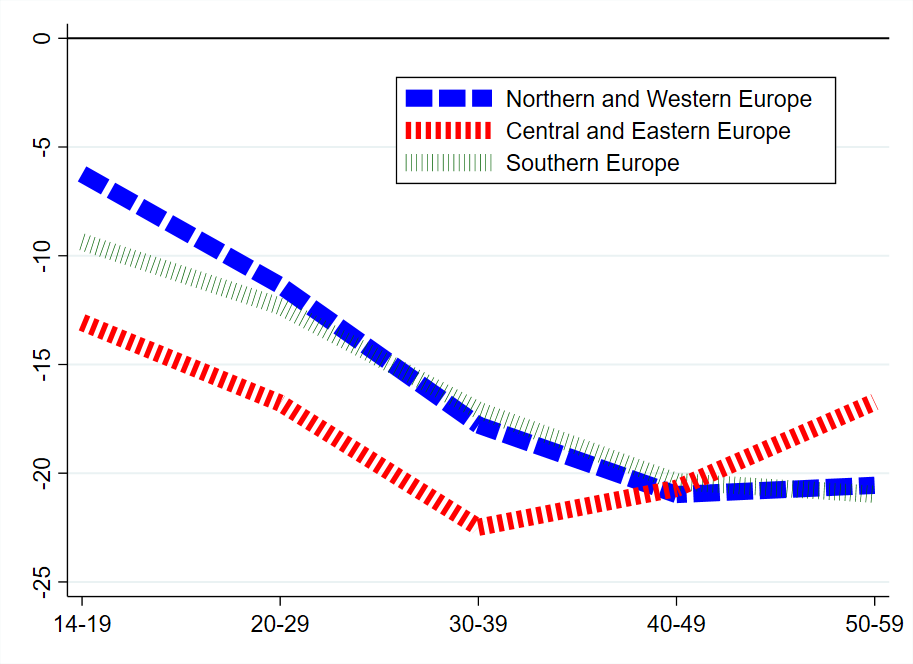

How do gender wage gaps vary over the course of women’s working lives? Answering this question can shed some initial light on their drivers. In Figure 2, we plot the evolution of gender wage gaps over the working life for broad geographical groups of countries.3

Figure 2 Differences in women’s hourly earnings relative to men over their working lives(%)

Note: The chart compares gender wage gaps over the working life-cycle across different country groups. It shows percent differences in women’s hourly earnings relative to men with the same level of educational attainment and tenure by age and country groups.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Eurostat Structure of Earnings Survey.

Gender wage gaps arise even among teenagers

Gender wage gaps arise even among teenagers (age 14–19), which is before most European women give birth to their first child. This could reflect discriminatory practices by employers. Discrimination may reflect conscious aversion to female employees and unconscious biases (taste-based discrimination), or the perception that women are on average less productive than men, for instance because they are expected to take long and costly leaves around childbirth (statistical discrimination). The ‘teenager gender wage gap’ could also be due to the existence of entrenched social norms that lead women to sort into low-paying occupations or industries. Discrimination and social norms appear to play a particularly important role in Central and Eastern European countries, where the teenager gap is about 13%, while they seem to be less important in Southern and particularly Northern and Western countries, where the teenager gap is respectively 9% and 6%.

Wage differences between women and men increase sharply around peak childbearing ages

Wage differences between men and women increase sharply at ages 20–29 and 30–39.4 Since this coincides with women’s peak childbearing ages, this pattern suggests that women face an important ‘child wage penalty’. What can explain the child penalty? In many European countries, parental leave is more generous for mothers than for fathers. Hence, mothers experience longer spells of labour market inactivity. This slows their accumulation of human capital, with adverse effects on wage growth. Moreover, as household chores disproportionately fall to women and increase with the birth of the first child, many mothers switch to part-time jobs, which are generally paid less per hour than full-time jobs. Working part-time may also negatively affect their career progression, as part-time workers accumulate less human capital and spend less time in the workplace, which is important to establishing the formal and informal bonds that are often key to obtaining promotions.

The child penalty may be particularly important in Northern and Western Europe, where the increase in the gender wage gap when moving from age 14–19 to age 30–39 is most pronounced. As we document in the paper, this region also witnesses much steeper increases in the gender wage gap among workers with a tertiary degree than among those with a basic education. Since career opportunities, and therefore scope for wage growth, are more limited among lower-skilled workers, this further suggests that difficulties in career progression are a key factor holding back women’s wages in Northern and Western European countries. By contrast, in Central and Eastern European countries, the gender wage gap increases more modestly when moving from age 14–19 to age 30–39 and even narrows as women enter their prime labour market ages (from 30–39 to 50–59). These patterns suggest that the child penalty may be smaller and more temporary in these countries.

Empirical decomposition of the drivers of the gender wage gap

Next, we formally decompose the gender wage gap into three deep drivers:

- Social norms, gender stereotyping, and discrimination

- Compensating wage differentials (the take-up of jobs with lower wages in return for specific non-wage characteristics, such as more flexible work arrangements), and

- Slowed human capital accumulation due to mothers interrupting their careers and/or transitioning to part-time work after giving birth to the first child.

The empirical approach combines life-cycle patterns of the gender wage gap with first-child fertility rates and rests on the following assumptions. First, social norms and discrimination are assumed to fully account for the gender wage gap at labour market entry, when the child penalty is unlikely to play a significant role. Second, compensating wage differentials are assumed to induce a one-off wage penalty for women around the time of childbirth. Third, slow human capital accumulation is assumed to lead to a gradual widening of the gender wage gap after childbirth. Figure 3 shows the results from this empirical decomposition.

Figure 3 The deep drivers of the gender wage gap across countries (percentage points)

Note: The chart shows drivers of the gender wage gap for each country, as estimated from the life-cycle accounting approach.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Eurostat Structure of Earnings Survey.

Discrimination and social norms account for about 60% of the gender wage gap in Central and Eastern Europe

Consistent with a large ‘teenager gap’, we find discrimination and social norms to account for about 60% of the gender wage gap in Central and Eastern European countries. As we show in the paper, these countries also display larger gaps in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) than in the private sector. Why does this matter? Discrimination reduces the demand for female workers, thus driving down their relative wages. Since in a competitive environment non-discriminating employers would have strong incentives to reduce their costs by employing more female employees, discrimination should be more widespread in less competitive markets, such as those in which SOEs typically operate. Over all, the findings from the life-cycle accounting approach, together with the evidence on SOEs, suggest the important role of discrimination and social norms in driving the gender wage gap in Central and Eastern Europe.

The child penalty explains 75% of the gap in Northern and Western Europe and around 70% in Southern Europe

Our empirical decomposition suggests a large contribution (about 75%) of the child penalty to the gender wage gap in Northern and Western European countries. The specific weight of compensating wage differentials is about twice as large as that of slow human capital accumulation. This is consistent with the fact that working-time status alone explains about 20% of the gender wage gap in these countries, as a large share of women transition from full- to part-time work during peak childbearing years. We also find that a non-trivial share of the gender wage gap is driven by differences in overtime earnings, which again supports the view that around childbearing peak childbearing ages Northern and Western European women work fewer hours than their male counterparts.

Regarding Southern European countries, our decomposition suggests that they are an intermediate case between those in Central and Eastern and Northern and Western Europe. The child penalty accounts for about 70% of the gender wage gap, with discrimination explaining the remaining 30%.

Bold and country-tailored policies are needed to close gender wage gaps in Europe

What can we conclude from our analysis? The drivers of the gender wage gap are multiple, and their importance differs widely across countries. The policy mix to close these gaps needs to be tailored to each individual country’s circumstances. Where compensating wage differentials are important, one focus of public policy could be to make non-wage job characteristics that are particularly valued by women more widely accepted by employers. For instance, in Denmark, which in 2002 gave workers the right to request a reduction in working time (with a pro rata reduction in monthly earnings but without re-negotiating the existing employment contract), a large proportion of both women and men work part-time and there is no wage penalty for part-time work. Governments could also promote policies to make telework an important aspect of post-COVID-19 labour markets. As telework reduces commuting times and allows for more flexible work schedules, it allows working mothers (and fathers) to spend more time on childcare without the need to switch to part-time jobs.

Especially in countries where slowed skill accumulation is an important driver of the gender wage gap, promoting flexible working arrangements should be complemented with measures to reduce the need for women to take up these arrangements in the first place. Such measures include family policies, like the provision of universal childcare and the harmonisation of parental leave for men and women. Reducing effective marginal tax rates on second earners would also promote female labour market participation and human capital accumulation. Evidence from Canada, Ireland, and Sweden suggests that the partial or complete individualisation of income taxation significantly raises the employment rate of married women (Doorley 2018, Selin 2014, Crossley and Jeon 2007).

Finally, many countries, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, need to reinforce policies to address discrimination against women. These may include promoting pay transparency, strengthening competition in product markets to drive out discriminating employers, raising wage floors where they are currently low, and combating gender stereotyping to reduce gendered educational and occupational sorting (Bertrand 2020).

Authors’ note: the views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the OECD nor its member countries.

References

Bertrand, M (2020), “Gender in the Twenty-First Century”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 110: 1–24.

Ciminelli, G, C Schwellnus and B Stadler (2021), “Sticky Floors or Glass Ceilings? The Role of Human Capital, Working Time Flexibility and Discrimination in the Gender Wage Gap”, Economics Department Working Paper No. 1668, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Crossley, T and S Jeon (2007), “Joint Taxation and the Labour Supply of Married Women: Evidence from the Canadian Tax Reform of 1988”, Fiscal Studies 28(3): 343–365.

Doorley, K (2018), “Taxation, Work and Gender Equality in Ireland”, IZA DP No. 11495.

Fabrizio, S, V Malta and M Tavares (2020), “COVID-19: A Backward Step for Gender Equality”, VoxEU.org, 20 June.

OECD (2018), OECD Employment Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing.

Queisser, M, W Adema and C Clarke (2020), “COVID-19, Employment and Women in OECD Countries”, VoxEU.org, 22 April.

Selin, H (2014), “The rise in female employment and the role of tax incentives. An empirical analysis of the Swedish individual tax reform of 1971”, International Tax and Public Finance 21(5): 894–922.

Sun, C and L Russell (2021), “The impact of COVID-19 childcare closures and women’s labour supply”, VoxEU.org, 22 January.

Endnotes

1 The analysis covers ten countries from Northern and Western Europe (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the UK); ten countries from Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia); and five countries from Southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey). The data come from the Structure of Earnings Survey (SES), a four-yearly survey that underpins Eurostat’s aggregate earnings statistics and contains worker-level information on earnings, hours worked, contract type, and demographic characteristics, as well as a firm identifier. The first survey was conducted in 2002. At the time of writing, data from the 2018 wave were not yet available, so our analysis draws from the 2002, 2006, 2010, and 2014 waves.

2 Low gender wage gaps in some countries are the mirror image of very large employment gaps. In countries such as Turkey Greece, and Italy, for instance, relatively few women actively participate in the labour market and those who do tend to have fairly high wages, which reduces the extent of observed wage gaps.

3 When studying the working life-cycle profile of gender wage gaps, it is usually difficult to disentangle age- from cohort-specific effects. This is especially true when the analysis is performed using cross-sectional data (all observations pertaining to the same period). Imagine that we could observe the entire population of country X in the year 2010. Then, to analyse the gender wage gap at ages 30 and 40, we would consider women and men born in 1980 and 1970 respectively. If the gender wage gap among those born in 1980 was smaller than that among those born in 1970, we might conclude that the gap increases when moving from age 30 to age 40. However, this could be a flawed conclusion if those born in 1980 had a lower gap than those born in 1970 or in the year 2000. In that case, it may simply be that the cohort of those born in 1980 had a lower gender wage gap than the cohort of those born in 1970 throughout the entire work life-cycle. Fortunately, our data allow us to observe the same cohort at different ages. Specifically, we observe a given cohort over 12 years, and age generally varies by ten-year age brackets, which allows us to disentangle age from cohort effects (see the paper for more details).

[1] SES data provide information on age only in terms of large brackets (14–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59).