A large amount of carry trade was drawn to Iceland in the boom leading up to the crisis of early October 2008 (Danielsson and Arnason 2011, Baldursson and Portes 2013a). As pressure mounted on the Icelandic banks, investors increasingly chose to exit the krona, which depreciated by 25% during the week before the banks collapsed. As the banks went down, the krona depreciated even further. Stopping the slide was imperative, because of the widespread use of foreign currency in domestic lending and extensive price-indexation of household debt, coupled with rapid pass-through from the exchange rate to domestic prices. The capital controls prevented further massive capital flight and a complete collapse of the exchange rate.

Although much of the carry trade stock had already left by the time of the crisis, the controls locked in remaining carry trade funds amounting to 40% of GDP. Half of these funds still remain in Iceland and would on their own make it difficult to lift the capital controls. But this is only part of the story. The domestic assets of the failed Icelandic banks also represent a huge obstacle to lifting the controls. These assets must be substantially restructured (Baldursson and Portes 2013b).

The old banks and the offshore krona overhang

When the three large Icelandic banks – Landsbanki, Glitnir and Kaupthing – collapsed in October 2008, deposits and deposit insurance were given priority over other claims on the banks. Domestic loans and deposits were transferred into new banks. Bondholders were left with claims to assets remaining in the old, failed banks, second in line after deposits and deposit insurance.

The margin of assets over liabilities at each new bank became a claim of the old bank on the new. In the case of Kaupthing and Glitnir, this claim eventually became a majority equity share of the old bank. In the case of Landsbanki – familiar to many from the Icesave story (Baldursson and Portes 2013a) – most of the claim took the form of a bond, now held by the old bank, and to be redeemed in 2015-18. The Icelandic state supplied most of the new equity for New Landsbanki and now owns it fully, but it took only a minority share in New Glitnir (now Islandsbanki) and New Kaupthing (now Arion Bank).

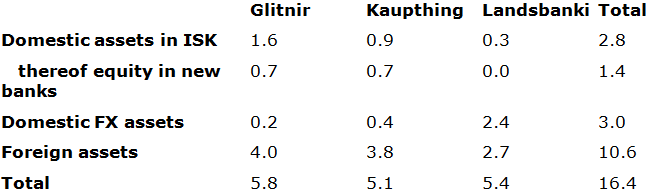

The old banks still formally exist as companies in bankruptcy process with total remaining assets of €16.4 billion (Table 1). For comparison, projected 2013 GDP is €11.15 billion (same conversion rate as in Table 1). Foreign creditors hold 95% of claims on the banks. Foreign assets are €10.6 billion, or 65% of the old banks’ total assets. They could be distributed to creditors without pressure on the exchange rate.

Table 1. Failed banks’ assets (End 2012. Amounts in € billions. Icelandic kronas converted to euros at 160 ISK/€)

Source: Central Bank of Iceland, Financial Stability Report (2013).

Approximately €5 billion has already been paid out to creditors – most of this by the old Landsbanki to deposit insurance funds in the UK and the Netherlands. Creditors of the banks have been pushing for progress in bankruptcy proceedings, so that further payments can be made, but the Central Bank of Iceland (CBI) is blocking this.

If the CBI would comply with these wishes, not only the banks’ foreign assets would be freed up, but also Icelandic krona denominated assets amounting to 23% of GDP, which would be added to the 19% of krona assets held by non-residents. The net foreign exchange requirement due to domestic FX assets corresponds to the Landsbanki bond, which amounts to 16% of GDP. With the ‘old’ carry trade overhang, the total foreign exchange required would thus rise to 58% of GDP.

International capital markets are still closed to Iceland, except for the sovereign; the underlying current account surplus (3% of GDP p.a.) is too small for Iceland to be able to finance outflows of this magnitude out of current income. Allowing the winding-up to proceed without intervention and no capital controls is impossible.

The CBI has signalled that a substantial reduction in the Icelandic krona holdings of Glitnir and Kaupthing, and a restructuring of the Landsbanki bond, are necessary conditions for lifting the capital controls (Gudmundsson 2013). Indeed, if these two conditions were met, then the offshore krona overhang could be manageable.

But there are major obstacles.

- The claims in question are on private parties – not the government or the CBI – so the Icelandic authorities are not in the position of a debtor negotiating for a restructuring with its creditors.

- The banks are in formal bankruptcy proceedings under Icelandic law, which in ordinary circumstances would be left to the winding-up boards and the creditors.

Strategic positions

At present, the CBI does have considerable legal powers to influence the resolution of the failed banks– provisions of the Foreign Exchange Act allow it to block payments out of the banks’ estates, indefinitely. As soon as payments in foreign currency out of the estates are allowed to go forward, however, the CBI will lose whatever power it had to influence the resolution process. It is, therefore, not surprising that the CBI has blocked further payments to creditors.

It is difficult for Icelandic authorities to take the initiative in this situation. The role of the authorities is first, and foremost, to look out for legitimate Icelandic interests– both safeguarding financial stability and the solvency of Iceland, and lifting the capital controls. But Iceland must in some sense be neutral vis-à-vis the banks’ creditors, and avoid being seen to apply coercive force.

Creditors of the old banks can, however, voluntarily suggest solutions to the current stalemate. (We use ‘voluntary’ here much in the same sense as the recent restructuring of Greek government bonds was voluntary, see Gulati et al. 2013.) Such a solution can be implemented in various ways. At Glitnir and Kaupthing a large haircut on Icelandic krona assets of the failed banks is necessary. Foreign assets constitute 70-80% of the book value of assets (Table 1). Hence, a 75% haircut, say, on krona holdings (the remaining 20-30% of assets), combined with full payout of foreign assets, would reduce payments to 80-85% of assets, implying an overall haircut of 15-20% of assets.

This might be an acceptable compromise for the majority of creditors at these banks. Many are distressed debt funds – colloquially often called vulture funds – which purchased their claims at heavily discounted prices and would make a handsome profit, multiplying their investment several times over, even with a substantial haircut on Icelandic assets.

As for Landsbanki, as soon as New Landsbanki would reach an agreement with its ancestor on restructuring the problematic bond, the CBI might allow payments to priority claimants to proceed. A restructuring involving an extension of maturity by twelve years, and a lowering of the interest rate, has been requested (Morgunbladid 2013). Landsbanki, however, constitutes a very different strategic case from that of Glitnir and Kaupthing for three main reasons.

- First, a contract (the bond) is already in place.

- Second, the main creditors of Landsbanki are the British and Dutch authorities.

- Third, the Icelandic state is the sole owner of New Landsbanki.

Should the UK and Dutch authorities refuse to restructure, and if the CBI refuses to grant the required foreign exchange, then New Landsbanki will be in default. Apart from wider-ranging concerns – financial stability, the credit rating of the sovereign, etc. – the Icelandic authorities will not want to see this happen to a bank fully owned by the state.

Possibly complicating matters, a new two-party coalition government has directly linked possible government revenues created by the winding-up of the old banks (e.g., through an exit tax) to the financing of debt relief for Icelandic households. Indeed, debt relief on price-indexed housing mortgage loans was the most prominent election promise of the new Prime Minister’s party. It is not clear how this will affect the outcome.

- On the one hand, this connection has put the CBI under pressure to achieve a large reduction in Icelandic krona holdings.

- On the other hand, the government is under pressure from a part of the electorate to live up to its promise as soon as possible.

That indicates impatience in achieving resolution, which weakens the position of the Icelandic authorities. There is also a risk that the Icelandic authorities would be seen to be motivated by the desire to profit in an illegitimate way from the winding-up of the old banks, rather than by the legitimate concerns mentioned earlier.

Policies on lifting the capital controls

Iceland faces a difficult, but not insurmountable, problem in resolving its failed banks and lifting capital controls. The stakes are high. It is important for the country’s future economic prosperity ultimately to lift the capital controls. This must, however, be done without endangering financial stability and national solvency. Even if the controls are damaging, the gains from lifting them are likely to be much lower than the costs associated with a currency crisis following a premature liberalisation of capital outflows (Gourinchas and Jeanne 2006, Coeurdacier et al. 2013, Obstfeld 2009, Rey 2013). Although Forbes and Klein (2013) find in a large sample that “new controls on capital outflows appear to have particularly negative effects, as they generate sharp and significant decreases in GDP growth”, it is hard to see such effects in the Icelandic recovery from the crisis, and easy to imagine the hugely disruptive consequences of lifting the controls without solutions to the problems we have described. So, patience is of the utmost importance on the Icelandic side.

In the cases of Glitnir and Kaupthing, a satisfactory outcome can probably be implemented by agreements with creditors and winding-up boards that involve foreign currency payment out of the failed banks’ estates, combined with an exit tax on Icelandic krona assets. Alternatively, there could be an exchange of assets in which long-dated low-interest bonds, denominated in foreign currency, would be exchanged for Icelandic krona assets.

As for the Landsbanki bond, one can only hope that even if the Icelandic, British, and Dutch authorities were at loggerheads over the Icesave issue, there is willingness to find a solution that does not compromise financial stability or sovereign solvency in Iceland. This requires goodwill at the highest political level.

The design of policy on lifting the capital controls requires consideration of other risks. These include the likelihood of domestic outflows, as well as fiscal and financial stability implications of rising yields on assets. Fiscal risks can be reduced by using possible proceeds from an exit tax to lower public debt.

It is tempting to compare Iceland to Cyprus, which has also imposed capital controls after the failure of large cross-border banks. There is, however, a key difference between these two countries– Cyprus’s membership of the Eurozone. The case of Iceland is certainly instructive, but with its failed large banks that are still unresolved, and still pose a threat to financial stability within the very small Icelandic currency area, it is unique.

References

Baldursson, Fridrik M and Richard Portes (2013a), “Gambling for resurrection in Iceland: the rise and fall of the banks”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9664, September.

Baldursson, Fridrik M and Richard Portes (2013b), “Capital controls and the resolution of failed cross-border banks: the case of Iceland”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9706, October. Forthcoming in Capital Markets Law Journal.

Coeurdacier, Nicolas, Hélène Rey and Pablo Winant (2013), “Financial Integration and Growth in a Risky World”, manuscript, London Business School and SciencesPo.

Danielsson, Jon and Ragnar Arnason (2011), “Capital controls are exactly wrong for Iceland”, VoxEU.org, 14 November.

Forbes, Kristin, and Michael Klein (2013), “Pick Your Poison: The Choices and Consequences of Policy Responses to Crises”, 14th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference, 7-8 November.

Gudmundsson, Mar (2013), Speech delivered at the 52nd Annual General Meeting of the Central Bank of Iceland, 21 March.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Olivier Jeanne (2006). “The elusive gains from international financial integration”, Review of Economic Studies, 73, 715-741.

Gulati, Mitu, Christoph Trebesch, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer (2013). “The Greek debt restructuring: an autopsy”, Economic Policy, issue no. 75, 513-563.

Morgunbladid (2013). “Lenging forsenda undanþágu” [‘Extension a condition for exemption’], 4 June.

Obstfeld, Maurice (2009). “International Finance and Growth in Developing Countries: What Have We Learned?” NBER Working Paper No. 14691.

Rey, Hélène (2013). “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence”. Paper for Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas Jackson Hole symposium, August, forthcoming in proceedings.