“The interaction of disparate cultures, the vehemence of the ideals that led the immigrants here, the opportunity offered by a new life, all gave America a flavour and a character that make it as unmistakable and as remarkable to people today as it was to Alexis de Tocqueville in the early part of the 19th century.”

John F. Kennedy, A Nation of Immigrants

Immigration is one of the most controversial policy issues in the US and Europe today. The debate mostly focuses on the short-run effects of immigration: Do immigrants take jobs away from natives? Do immigrants increase pressure on public goods? Do immigrants increase crime and reduce social capital? Many researchers have attempted to address these questions by providing empirical evidence on the short-run, immediate effects of immigration (e.g. Kerr and Kerr 2016, Peri 2012, Peri and Sparber 2009, Card 2009, 2012). While understanding the short run is important, policymakers should also consider the long-run consequences if the welfare of our children and grandchildren are to matter. And yet, we know very little about the long-run impact of immigration.

The long-run effects of immigrants can, in principle, be positive or negative. On the one hand, immigrants can supply much needed labour. They can also bring new knowledge and skills that complement the skills of native born workers. On the other hand, immigrants are often associated with social unrest and crime. This is especially worrying in cases where the flow of immigrants is large relative to the native population, or if the immigrants are from very different cultural backgrounds. Ethnic diversity could make it harder for communities to agree on which public goods they need such as schools or roads, and thus lower the provision of public goods that are important for long-run growth. A related concern is that allowing large flows of immigrants who are relatively uneducated may reduce overall educational attainment in the region in the long run.

To study this question, in a recent paper we examine migration into the US during America’s Age of Mass Migration (from 1850–1920) and estimate the causal effect of immigrants on economic and social outcomes approximately 100 years later (Nunn et al. 2017). This period of immigration is notable for many reasons. First, this was the period in US history with the highest levels of immigration. Second, the immigrants that arrived during this time were different from previous waves of immigrants. While earlier immigrants were primarily from western Europe, the new wave also included large numbers of immigrants from southern, northern, and eastern Europe who spoke different languages and had different religious practices (Hatton and Williamson 2005: 51, Daniels 2002: 121–137, Abramitzky and Boustan 2015).

Empirically studying the long-run effects of immigration is challenging. A natural strategy is to examine the relationship between historical immigration and current economic outcomes across counties in the US However, there are important shortcomings to such an exercise. There may be persistent omitted factors that affected immigration decisions that could independently influence the outcomes of interest. It is also possible that immigrants were attracted to locations with more growth potential. Alternatively, they may have only been able to settle in more marginal locations, where land and rents were cheaper and future economic growth was lower. These concerns would cause the OLS estimates to be biased.

We attempt to overcome these challenges by developing an instrumental variable (IV) strategy that exploits two facts about immigration during this period. The first is that after arriving into the US, immigrants tended to use the newly constructed railway to travel inland to their eventual place of residence (Faulkner 1960, Foerster 1969). Therefore, a county’s connection to the railway network affected the number of immigrants that settled in the county. The second fact is that the aggregate inflow of immigrants coming to the US during this period fluctuated greatly from decade to decade.

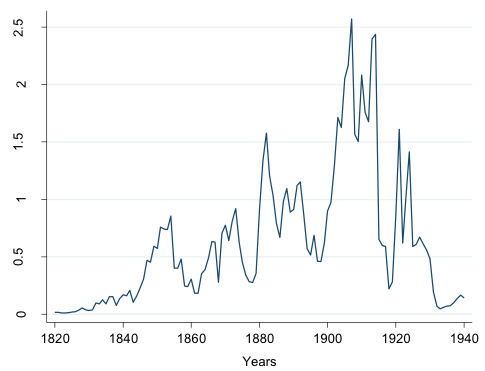

Figure 1 Total immigrants arriving in the US by year

This fluctuation is driven, in part, by weather shocks in the origin countries of immigrants. For example, more German immigrants arrived following a drought in Germany. Holding constant the total length of time a county was connected to the railway network, if a county was connected to the railway network during periods of high aggregate immigration to the US, then the county would tend to have had more immigrant settlement during the entire period of mass migration (1860–1920).

We find that higher historical immigration (from 1860–1920) resulted in significantly higher incomes, less poverty, less unemployment, more urbanisation, and higher educational attainment today. The estimates, in addition to being statistically significant, are also economically meaningful. For example, according to the estimates for per capita income, moving a county with no historical immigration (i.e. during 1860–1920) to the 50th percentile of the sample (which is 0.049) results in a 20% increase in average per capita income today.

We also try to shed light on the mechanisms. We find that immigration resulted in an immediate increase in industrialisation. Immigrants contributed to the establishment of more manufacturing facilities and to the development of larger facilities. We also found that immigrants contributed to increased agricultural productivity in the medium-run and to increased innovation, as measured by patenting rates of both immigrants and the native-born. These findings are consistent with a long-standing narrative in the historical literature suggesting that immigrants benefitted the economy by providing an ample supply of unskilled labour, which was crucial for early industrialisation. A smaller number of immigrants brought with them knowledge, skills, and know-how that were beneficial for industry and increased productivity in agriculture. Thus, by providing a sizeable workforce and a (smaller) number of skilled workers, immigration led to early industrial development and long-run prosperity, which continues to persist until today.

One concern is that the economic benefits to counties with a higher share of immigrants came at the cost of less economic activity in other counties. We would then be capturing the relocation of economic activity as opposed to the creation of economic activity. However, we find no evidence for this type of negative spillover. A second concern relates to potentially negative social effects associated with mass migration. The immigration backlash and the rise of social and political nativist movements at the time suggest that there may have been initial social costs to immigration. We find no evidence that these costs persisted since higher historical immigration is not associated with higher crimes, lower voter turnout or lower social capital today.

Taken as a whole, our estimates provide evidence consistent with an historical narrative that is commonly told of how immigration facilitated economic growth. Extrapolating from these historical results to the current debate on migration requires some caution. The Age of Mass Migration occurred during a period of rapid industrialisation, where both demand for labour and land availability were high. There are, however, many similarities between the period of mass migration and today. The historical immigrants were similar to today’s immigrants in being very different from the natives. New arrivals from eastern, central, northern and southern Europe spoke different languages and followed different religions. Immigrants in both contexts are comprised of largely less educated workers with a smaller fraction of highly-skilled workers. And in both cases, many of the immigrants are ‘pushed’ out of their own countries due to economic or political shocks.

According to our results, the long-run benefits of immigration can be large and realised quickly. These effects persist across time and need not come at high social cost. This suggests the importance of taking a long-run perspective on the current immigration debate. Learning from past experience can not only highlight the long-run benefits of immigration, but also remind us that our policies today will have long-standing effects for future generations.

References

Abramitzky, R and L Platt Boustan (2016), “Immigration in American history”, Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.

Card, D (2009), “Immigration and inequality”, Journal of the European Economic Association 99(2): 211–215.

Card, D (2012) “The elusive search for negative wage impacts of immigration”, Journal of the European Economic Association 10(1): 1–21.

Daniels, R (2002) Coming to America: A history of immigration and ethnicity in American life, New York: Harper Perennial.

Faulkner, H U (1960), American Economic History, New York: Harper and Row Publishers.

Foerster, R (1969) The American immigration collection, New York: Arno Press Inc.

Hatton, T J and J G Williamson (2005) Global migration and the world economy: Two centuries of policy and performance, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kerr, S P and W R Kerr (2017) “Immigrant entrepreneurship”, in Haltiwanger, Hurst, Miranda, and Schoar (eds), Measuring entrepreneurial businesses: Current knowledge and challenges, University of Chicago Press.

Nunn, N, N Qian and S Sequeira (2017), “Migrants and the Making of America: The Short and Long Run Effects of Immigration During the Age of Mass Migration”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11899.

Peri, G (2012) “The effects of immigration on productivity: Evidence from US states”, Review of Economics and Statistics 94(1): 348–358.

Peri, G and C Sparber (2009) “Task specialization, immigration, and wages”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1(3): 135–169.