Just-in-time (JIT) production is a management philosophy that aims to minimise the time between orders. Originating in Japan with Toyota’s Kanban System (Ohno 1988), JIT has been adopted worldwide over the last several decades. The primary appeal of JIT is that it allows firms to cut costs by placing small and more frequent order batches rather than carrying large stocks of inventories.

Do improvements in inventory management matter for macroeconomics? Theoretically, inventories have been found to be neither a stabilising nor a destabilising force in general equilibrium (e.g. Khan and Thomas 2007). These studies suggest that improvements in inventory management are broadly inconsequential at the macro level.

More recently, supply chain disruptions have garnered considerable attention amid the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. Baldwin and Freeman 2020, Pisch 2020). Motivated by this, in a recent paper Ortiz (2021), I offer a new perspective on the role of inventories in driving aggregate fluctuations, finding that JIT production engenders macro-fragility in the face of large adverse tail events.

Facts about just-in-time firms

Empirically, I measure leanness among publicly traded US manufacturers from 1980 to 2018 by recording the years in which firms announce the adoption of JIT production. This approach follows Kenney and Wempe (2002) and Gao (2018). Based on this measure, I document two sets of facts about JIT producers which jointly suggest that JIT firms enjoy higher profits, yet they are more exposed to external events.

First, JIT producers appear to be more profitable. I find that firms experience a 9% increase in sales and a 13% decline in inventory holdings following JIT adoption. In addition, JIT producers experience a roughly 7% decline in employment and sales growth volatility relative to their non-JIT counterparts. My macroeconomic model is able to replicate these endogenous patterns. In the model, more productive firms adopt JIT production and subsequently enjoy lower inventory management costs, thereby raising sales. In addition, through JIT adoption, these firms mute their respective inventory cycles, leading to a dampening of firm-level fluctuations.

Second, JIT firms exhibit more volatility conditional on external events. For instance, relative to non-JIT firms, sales growth and employment growth among JIT producers co-move more closely with GDP growth, indicating that these producers are more exposed to the business cycle. Moreover, using data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), I find that JIT producers experience sharper sales and employment declines relative to non-JIT firms amid the onset of a weather events in the zip codes in which they are headquartered. These firms exhibit similar excess exposures to upstream weather events affecting their suppliers.

Quantifying the trade-off in a model of lean production

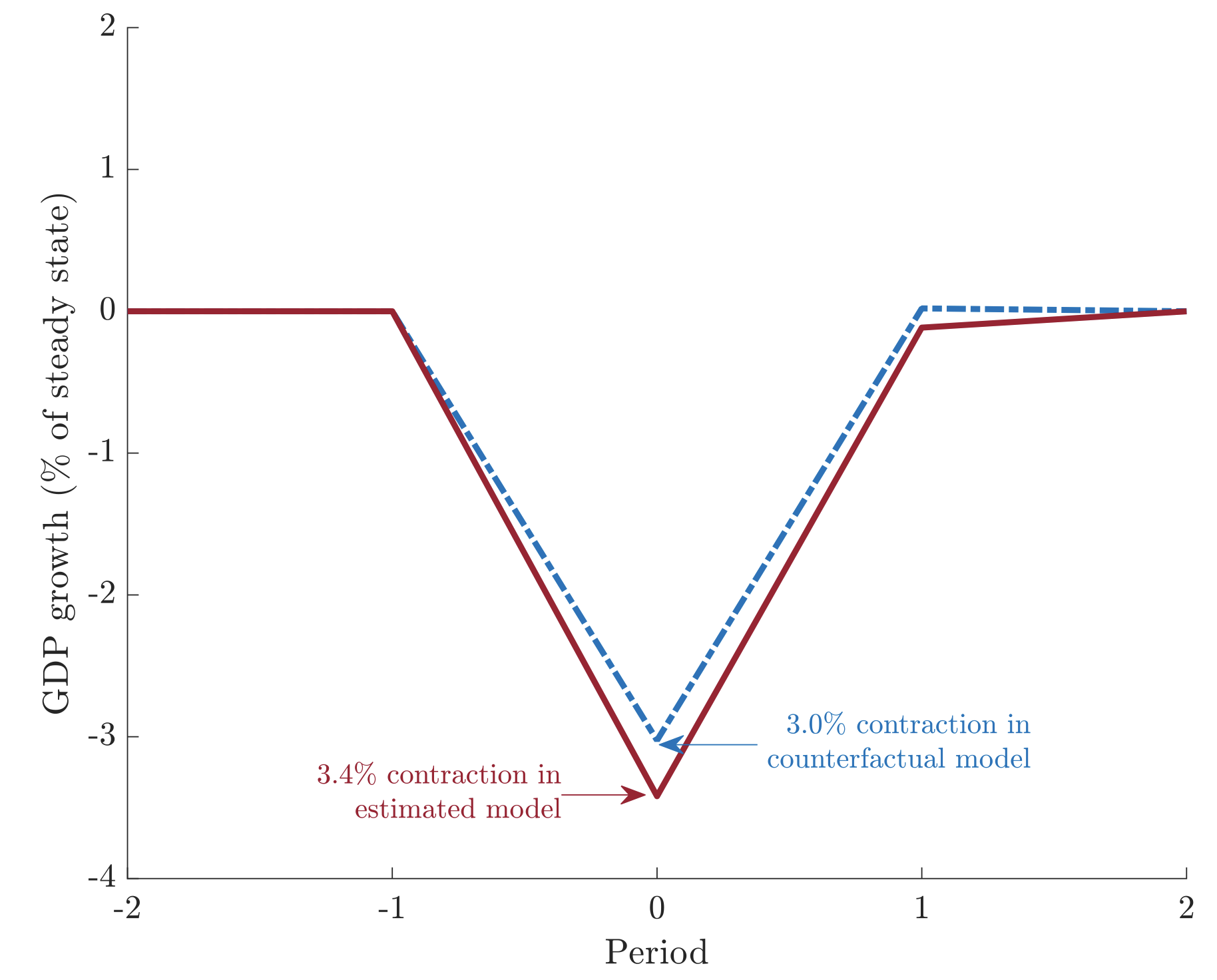

Figure 1 Deeper crisis with more JIT production

Taken together, the empirical patterns provide motivating evidence suggestive of a trade-off. Ultimately, my focus is on the interaction between JIT production and aggregate shocks. As a result, I extend a macroeconomic model of inventory investment to feature JIT production with a focus on unanticipated supply disruptions. As in Khan and Thomas (2007), firms in the model pay a fixed cost whenever they place an order. This leads firms to place relatively larger orders, and to carry unused materials (i.e. inventories) across time to avoid paying the fixed order cost in every period. JIT producers in the model benefit from lower order costs, which cause them to carry fewer inventories on average, consistent with JIT practices in reality.

After building the theoretical model, I take it to the data, estimating the firm-level productivity process as well as costs associated with ordering materials, storing inventories, and adopting JIT production. I then compare the estimated JIT model to a no-JIT counterfactual.

Focusing on the long-run outcomes across the two models, I find that the JIT economy exhibits about a 40% decline in the aggregate inventory-to-sales ratio, consistent with the decline in nonfarm inventory-to-sales in the US since 1980. In addition, when moving from the no-JIT economy to the JIT economy, output rises by about 10%, firm value rises by 1.3%, and welfare rises by 1.4%. The efficiency gains come from the fact that JIT firms are better able to align their firm’s productivity with material input usage, without being burdened by carrying idle stocks of inventories.

The other side of the trade-off relates to the vulnerabilities that JIT exposes. To examine this, I consider an unexpected supply shock that raises the marginal cost of orders. The supply disruption is calibrated such that it generates a 3.4% contraction in the JIT economy, in line with the decline in US economic activity in 2020. I then feed the same unexpected shock into the no-JIT counterfactual and find that the crisis is shallower, with an output contraction of 3%.1 The roughly 15% excess output contraction, which is attributed solely to JIT adoption, amounts to about a $100 billion gap and is comparable to the funds allocated for state and local governments with the passage of the CARES Act.2

The deeper contraction in the JIT economy is attributable to (1) more stockouts and (2) a slower drawdown of inventories. Due to the spike in the marginal cost of orders, firms in the JIT economy are more likely to find themselves in a scenario in which they have exhausted their inventories and are unable to procure more materials amid the disaster. This leads to the relative spike in stockouts. At the same time, firms that have not stocked out opt to deplete their inventories more slowly in an effort to not have to source new materials amid the supply disruption. Put another way, these firms choose to reduce their material input usage, leading to a sharper drop in sales relative to the no-JIT benchmark.

I proceed to quantify the trade-off for a range of counterfactual economies, each with a different level of JIT adoption. Figure 2 traces out this frontier. The vertical axis plots the firm value gains to JIT production in normal times while the horizontal axis plots the excess output contraction (in percentages) amid the unexpected supply disruption. As the arrow indicates, moving up and to the right along the frontier amounts to considering counterfactual economies with more JIT production. The red dot in Figure 2 denotes where I estimate the US economy to reside along this trade-off.

Figure 2 The micro-macro JIT trade-off

Concluding remarks

Even though leanness can make supply disruptions more severe, locating society on a point along the trade-off where there is less JIT adoption might not be desirable. The welfare implications of JIT production depend upon the size, severity, and frequency of the large unanticipated tail event. In my analysis, I show that JIT production remains welfare-improving amid a COVID-19-like shock. Furthermore, examining alternative drivers of JIT adoption is also important for the assessing the policy implications of this trade-off. While the trade-off is a consequence of JIT production (leanness), the welfare implications of JIT production likely depend on what persuades firms to go lean in the first place.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System.

References

Baldwin, R and R Freeman (2020), “Supply chain contagion waves: Thinking ahead on manufacturing ‘contagion and reinfection’ from the COVID concussion”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (2020), H.R. 748, 116th Congress.

Gao, X (2018), “Corporate cash hoarding: The role of just-in-time adoption”, Management Science 64: 4471-4965.

Kinney, M R and W F Wempe (2002), “Evidence on the extent and origins of JIT’s profitability effects”, The Accounting Review, 77: 203-225.

Khan, A and J Thomas (2007), “Inventories and the business cycle: An equilibrium analysis of (S,s) policies”, American Economic Review 97: 1165-1188.

Ohno, T (1988), Toyota production system: Beyond large-scale production, productivity press.

Ortiz, J L (2021), “Spread too thin: The impact of lean inventories”, Working paper.

Pisch, F (2020), “Just-in-time supply chains after the COVID-19 crisis”, VoxEU.org, 30 June.

Endnotes

1 As discussed in Ortiz (2021), this finding is robust to different parametrizations, other disaster sizes, as well as the introduction of an added stockout avoidance motive, and partial anticipation of the disaster.

2 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, H.R. 748, 116th Congress (2020).