In most advanced economies, a substantial share of the workforce is employed in the public sector. In 2017, in OECD countries, government employment represented on average 18% of total employment (OECD 2019). Despite its quantitative importance, public sector employment has traditionally received little attention by economists. According to Garibaldi and Gomes (2020), in the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper series, only two out of 10,510 papers published between 2000 and 2010 mention public sector employment in their title or abstract. At the same time, policymakers consider public employment as one way to support economically lagging regions. This raises the question whether public sector employment benefits local economies above and beyond the creation of those public sector jobs.

The idea that expansions in employment in a tradable sector can have multiplier effects on employment in other sectors in the same location has a long history (e.g. Daly 1940). The early literature in this area uses simple cross-sectional correlations or input-output approaches to estimate multipliers and struggles to isolate plausibly exogenous variation. To overcome these problems, researchers have turned to exploiting exogenous variation in employment in one sector to study spillovers into other sectors. For instance, Moretti (2010) uses a shift-share instrument to isolate exogenous variation in manufacturing employment across US cities. He estimates that an additional job in the tradable sector of a US city creates 1.6 additional jobs in the city’s non-tradable sector, with a larger multiplier effect for additional skilled jobs.

Given the importance of public sector employment in the economy, there is surprisingly little systematic evidence on the spillover effects of changes in the spatial distribution of public employment on the private sector. Yet, the distribution of public employment across locations should have important impacts on the location of private sector activity through its general equilibrium impact on wages and house prices and also through potential productivity and amenity spillovers from the public to the private sector.

Over the last few years, some studies have looked at private sector responses to public sector employment. Faggio and Overman (2014) use data from 325 UK local authorities during the period 2003 to 2007 and find that increases in public sector employment have a small but statistically insignificant positive effect on overall private sector employment. Faggio (2019) uses a difference-in-differences approach on data covering 2003-2008 to evaluate relocations of public sector employment from London recommended by the Lyons Review, finding broadly similar results to Faggio and Overman (2014). Auricchio et al. (2020) estimate the effect of changes in public employment on private employment across Italian municipalities using data from the 2001 and 2011 censuses. Jofre-Monseny et al. (2020) simulate the impact of public on private employment in a search and matching model and also show reduced-form evidence using Spanish data for 1980, 1990, and 2001. What is common to these studies is that they look at comparatively small variations in public employment and a shorter time horizon.

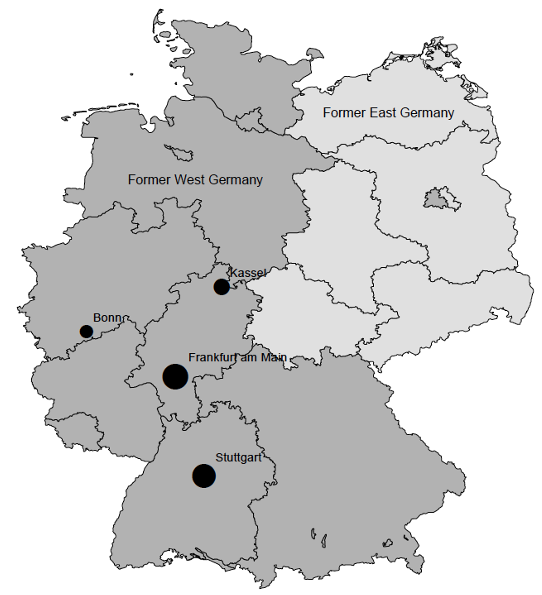

In a recent paper (Becker et al. 2020b), we study the massive increase in public sector employment in Bonn resulting from the decision to make it the capital city of West Germany after WWII. After Germany was defeated in WWII, it was divided into a capitalist West and a communist East (Becker et al. 2020a). Bonn became the capital of West Germany in 1949, beating the larger contenders Kassel, Stuttgart, and Frankfurt (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Bonn and other contenders for the Western German capital

Source: Becker et al. (2020b)

Picking the small city of Bonn was seen as a signal that the division of Germany was temporary. Yet, the division lasted 41 years. To construct a credible counterfactual to Bonn’s actual public sector and private sector employment trajectory, we use the so-called synthetic control method. This method acknowledges the fact that a simple average of other cities may not be a good enough control, and instead lets the data speak and searches for a weighted average of cities that best mimics the pre-treatment trend (predictors) in Bonn. More specifically, starting from a pool of 40 potential control cities, the synthetic control method chooses the city weights such that the synthetic Bonn most closely resembles the actual one before 1949. Any difference between the actual Bonn and the synthetic Bonn after 1949 is interpreted as resulting from Bonn surprisingly becoming the capital city of West Germany.

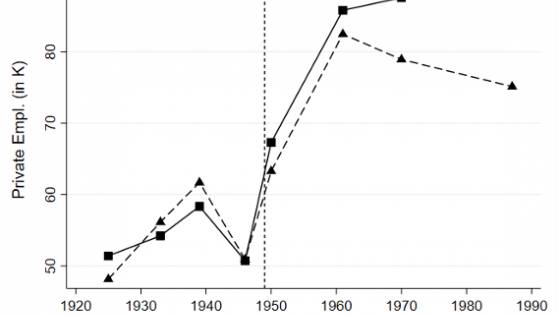

Figure 2 shows the trajectory of Bonn’s public employment (solid line) compared with the synthetic Bonn (dotted line with triangles).

Figure 2 Public sector employment in Bonn compared with a synthetic Bonn

Source: Becker et al. (2020b)

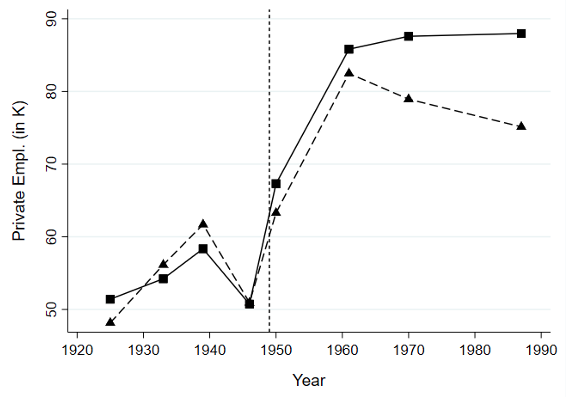

However, this results in only modest increases in private sector employment (see Figure 3) with each additional public sector job destroying around 0.2 jobs in industry and creating just over one additional job in other parts of the private sector.

Figure 3 Private sector employment in Bonn compared with a synthetic Bonn

Source: Becker et al. (2020b)

We interpret our results in the context of a simple theoretical model and explore the mechanisms through which public and private sector employment interact. We first provide reduced-form evidence that suggests that the main mechanism through which public employment helps private sector development is an increase in endogenous consumption amenities in Bonn while productivity in the private sector has at best been unchanged. A quantitative analysis of our theoretical model finds complementary results. While the best fit parameter for the estimated productivity spillovers of public employment is negative and close to zero, the best fit parameter for the estimated amenity spillovers of public employment is positive and much larger.

More broadly our results contribute to the debate of whether changes in the level of public employment are a viable policy instrument to support economically lagging regions. As our natural experiment involves the creation of a new federal government that naturally attracts diplomats, lobbyists, and visitors, our estimated effects should be an upper bound for the positive spillover effect that additional public sector employment can generate in the private sector. Some of what we capture as amenity spillovers could, for example, be driven by political economy forces that direct additional government expenditure on cultural amenities to Bonn. This implies that increasing the number of more mundane types of public employment in lagging regions could have even smaller spillover effects on private sector activity in the targeted regions. Public sector employment therefore seems unlikely to be a magic bullet to kickstart a local economy.

References

Auricchio, M, E Ciani, A Dalmazzo and G de Blasio (2020), “Life after public employment retrenchment: evidence from Italian municipalities”, Journal of Economic Geography 20(3): 733–782.

Becker, S O, L Mergele and L Woessmann (2020a), “German division and reunification and the ‘effects’ of communism”, VoxEU.org, 5 April.

Becker, S O, S Heblich and D M Sturm (2020b), “The Impact of Public Employment: Evidence from Bonn”, Journal of Urban Economics, forthcoming.

Daly, M C (1940), “An Approximation to a Geographical Multiplier”, The Economic Journal 50(198/199): 248–258.

Faggio, G (2019), “Relocation of Public Sector Workers: Evaluating a place-based policy”, Journal of Urban Economics 111: 53 – 75.

Faggio, G and H Overman (2014), “The Effect of Public Sector Employment on Local Labour Markets”, Journal of Urban Economics 79: 91–107.

Garibaldi, P and P Gomes (2020), The Economics of Public Employment: An Overview for Policy Makers, Fondazione Rodolfo de Benedetti Policy Report.

Jofre-Monseny, J, J I Silva and J Vázquez-Grenno (2020), “Local labor market effects of public employment”, Regional Science and Urban Economics 82: 103406.

Moretti, E (2010), “Local Multipliers”, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 100(2): 1–7.

OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019.