People continue to live longer and retire earlier than the generations that preceded them. This puts significant pressure on social security systems, as individuals contribute to pensions for fewer years and receive pension benefits for more years than they ever have.

Policymakers have used a variety of policy tools to preserve the solvency of social security systems. In recent work (Lalive et al. 2020), we exploit a unique and multi-faceted reform to women’s pensions (old age survivor’s insurance) in Switzerland to gain a deeper insight into the forces that shape decision-making in a high-stakes setting. In particular, we study how the decisions of when to claim pensions and exit the labour force respond to different commonly used policy instruments.

Economists tend to think that both decisions are shaped by financial incentives, as the life-cycle model of behaviour would predict. Recent studies (Behaghel and Blau 2012, Seibold 2020) have posited that decisions around pension claiming and retirement are shaped by reference dependent preferences together with loss aversion. Whether incentives or biases shape pension decisions is a key issue and it can be studied when incentives and biases give off conflicting signals – as does the Swiss reform we study.

The reform is especially notable because it gradually increased the full retirement age (the earliest age at which an individual can claim full pension benefits) in the first two phases while changing only the financial incentive schedule in the third phase, allowing us to study responses to different types of social-security policy change in relative isolation.

Prior to the reform, the full retirement age was 62. The reform first increased the full retirement age from age 62 to 63 for women born on or after 1 January 1939, and then from 63 to 64 years for women born on or after 1 January 1942. Under the reform, affected individuals could claim pensions before the new full retirement age (but not before age 62) at a price of 3.4% of benefits per year early. This price was unfair in the sense that the average Swiss woman could expect to accumulate greater lifetime social security wealth the earlier she claimed benefits, despite the penalty for early claiming.

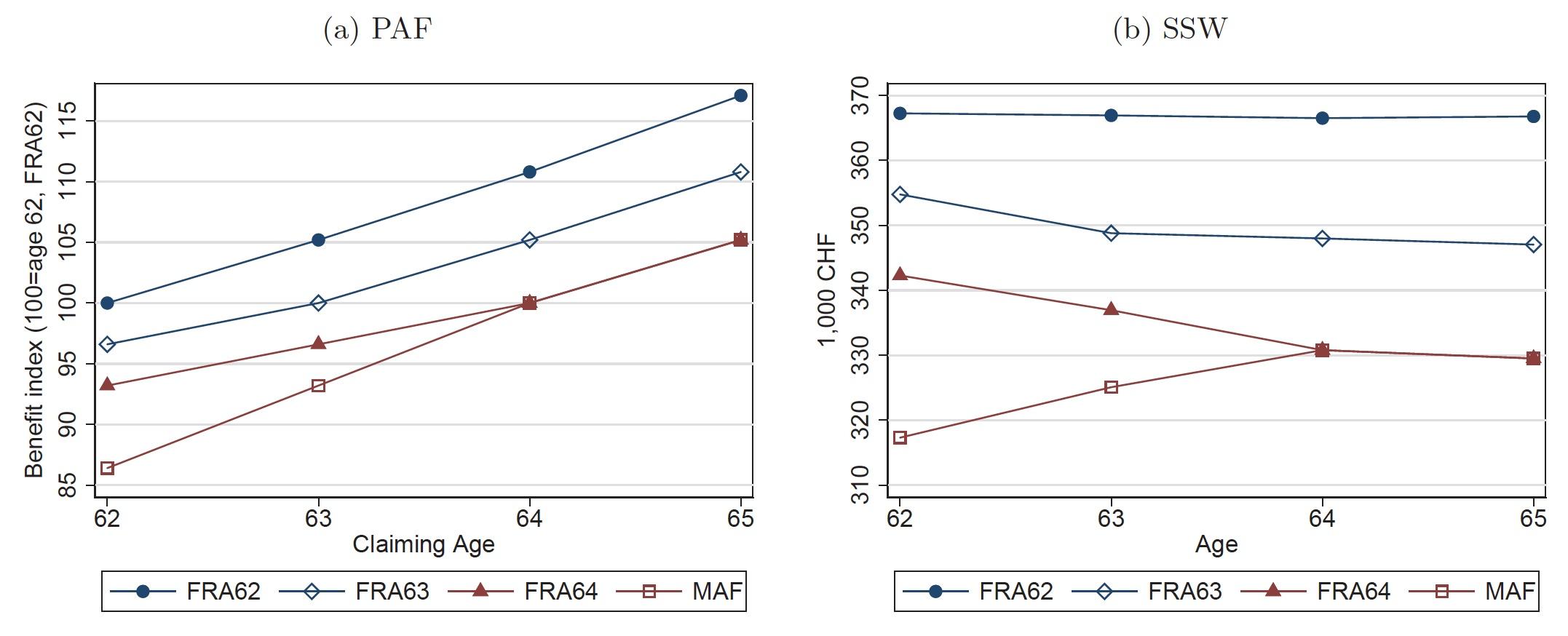

The third and final step of the reform increased the penalty for early claiming to 6.8% for women born on or after 1 January 1948, a greater than actuarially fair increase – now, claiming at the full retirement age maximised lifetime social security wealth. The reform and its effects on social security wealth are depicted in Figures 1(a) and (b).

Figure 1 Pension reform and its effects on social security wealth

Notes: PAF – pension adjustment factor; SSW – social security wealth; FRA – full retirement age.

From our perspective as researchers, the reform is useful for a few reasons:

- First, it generates sharp discontinuities in the full retirement age and the penalties for early claiming, allowing us to apply a credible regression discontinuity research design.

- Second, the first two stages of the reform increased the age at which it is deemed normal to claim benefits while making it less actuarially attractive to do so, and the last stage left the full retirement age fixed while making it more attractive to delay claiming. By comparing responses to the different stages of the reform, we can get a sense of the degree to which financial incentives shape behaviour relative to behavioural bias.

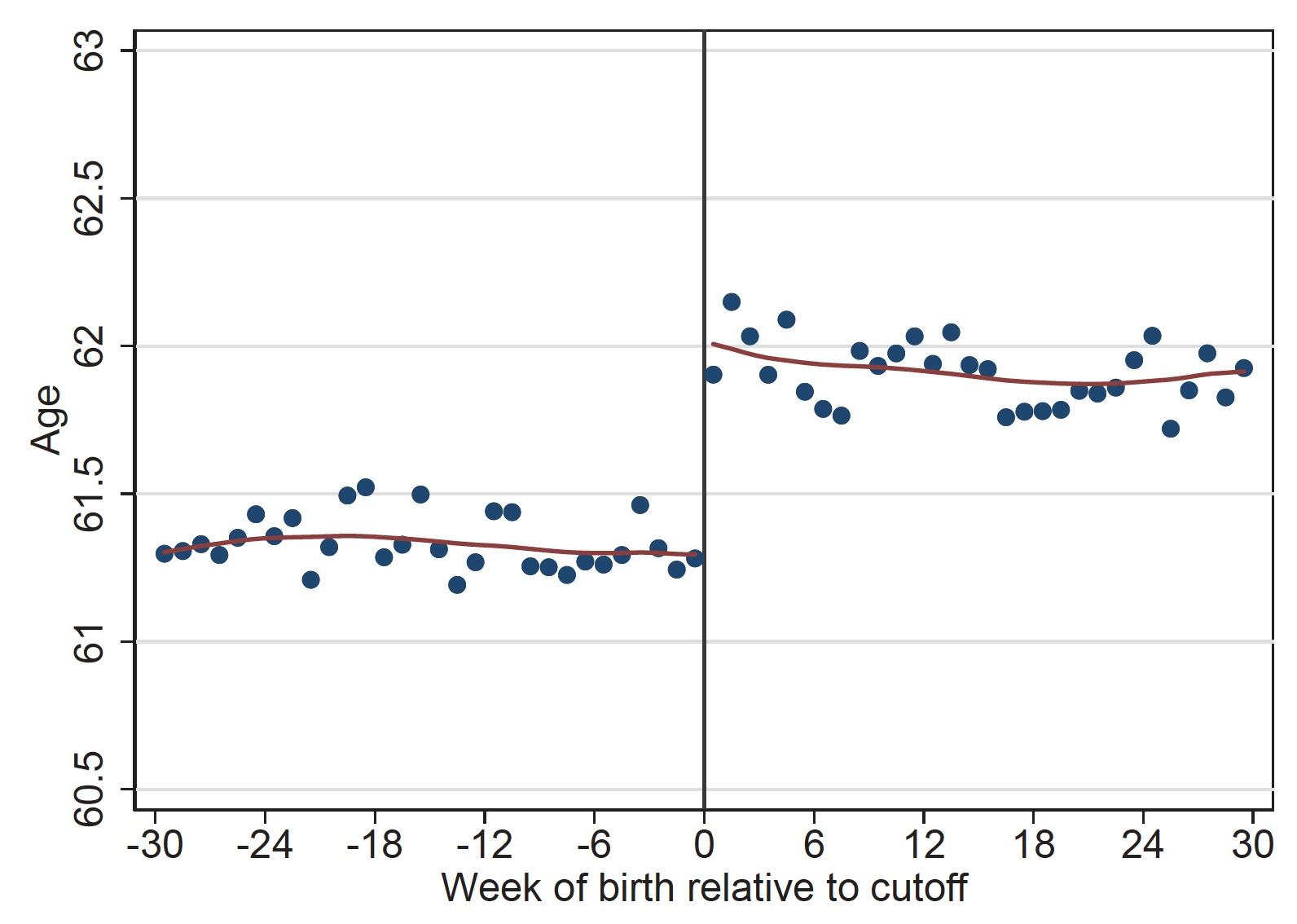

- Finally, in the Swiss setting, pension claiming and retirement are not mechanically linked, so that individuals can claim and continue working or retire early and not claim benefits. This allows us to study the effect of the reform on pension claiming and retirement decisions separately. Figure 2 illustrates claiming behaviour around the sharp discontinuity generated by the reform.

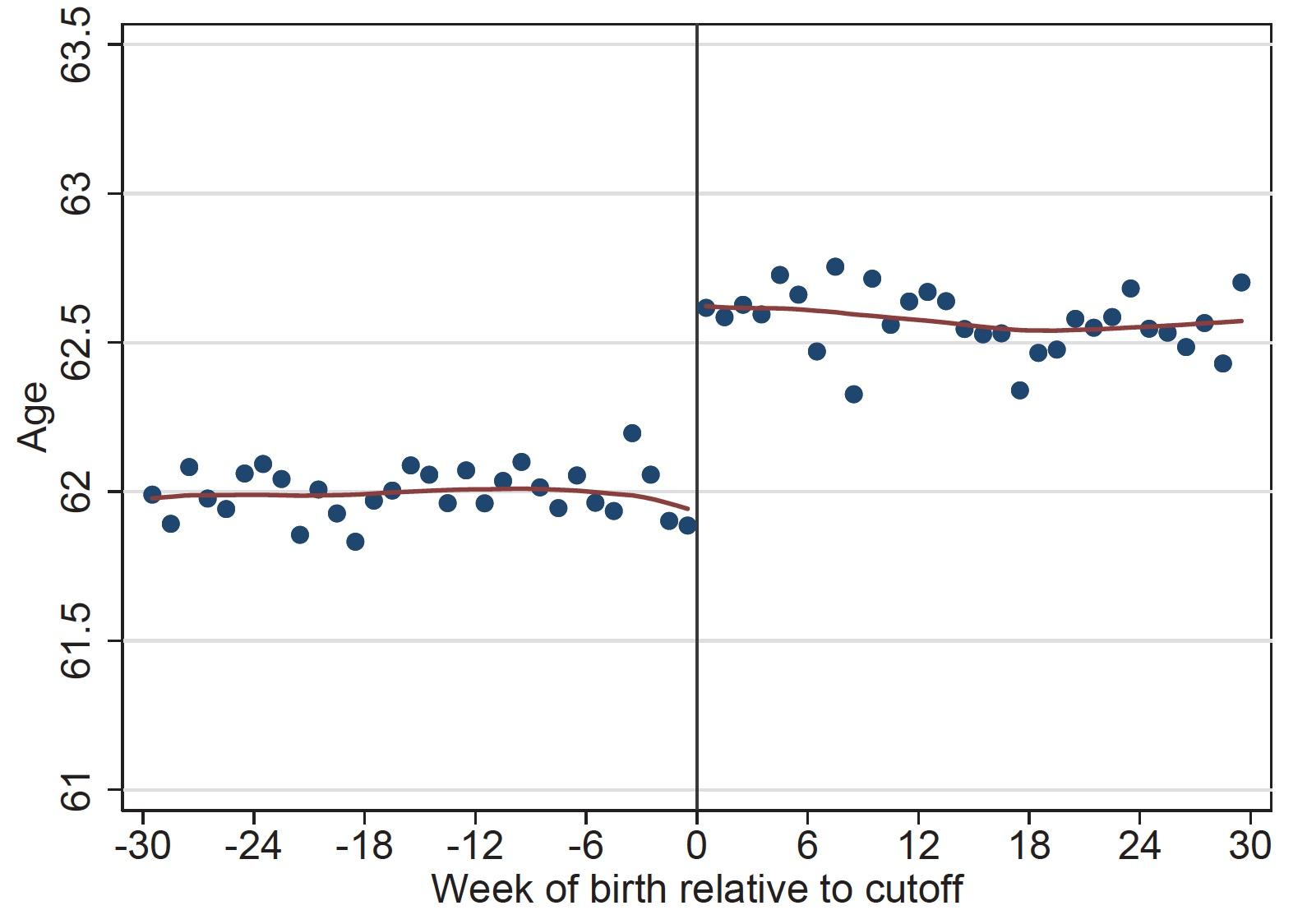

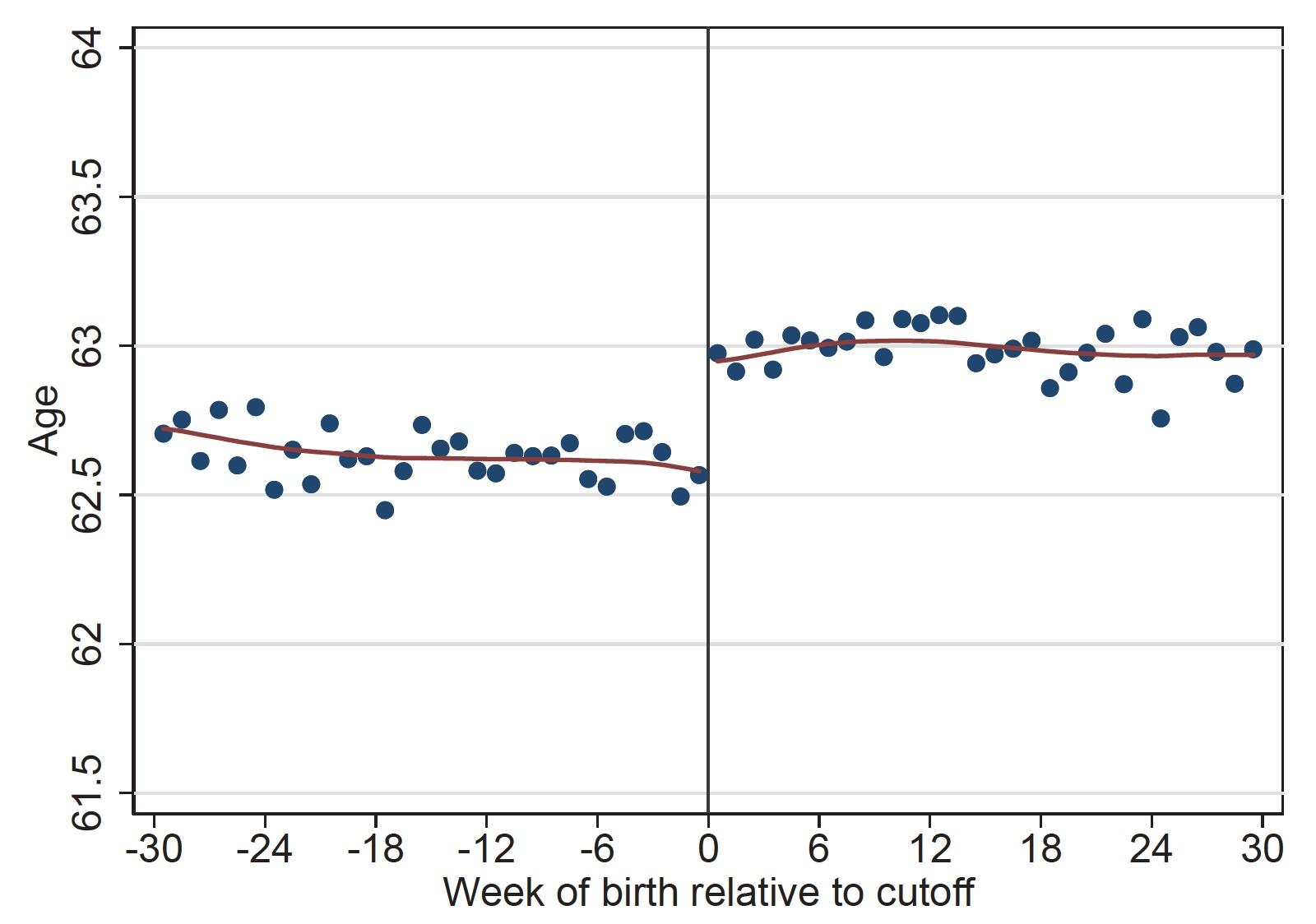

Figure 2 Pension-claiming behaviour around the sharp discontinuity generated by the reform

a) First reform stage

b) Second reform stage

c) Third reform stage

Our baseline finding is that increasing the full retirement age and offering early claiming at a low penalty of 3.4% delays pension claiming by 7–8 months, even though the average individual would receive higher lifetime social security wealth by claiming early while increasing the penalty for early claiming to 6.8% and holding the full retirement age fixed delays pension claiming by about 4 months. Figure 3 illustrates retirement behaviour around the discontinuity.

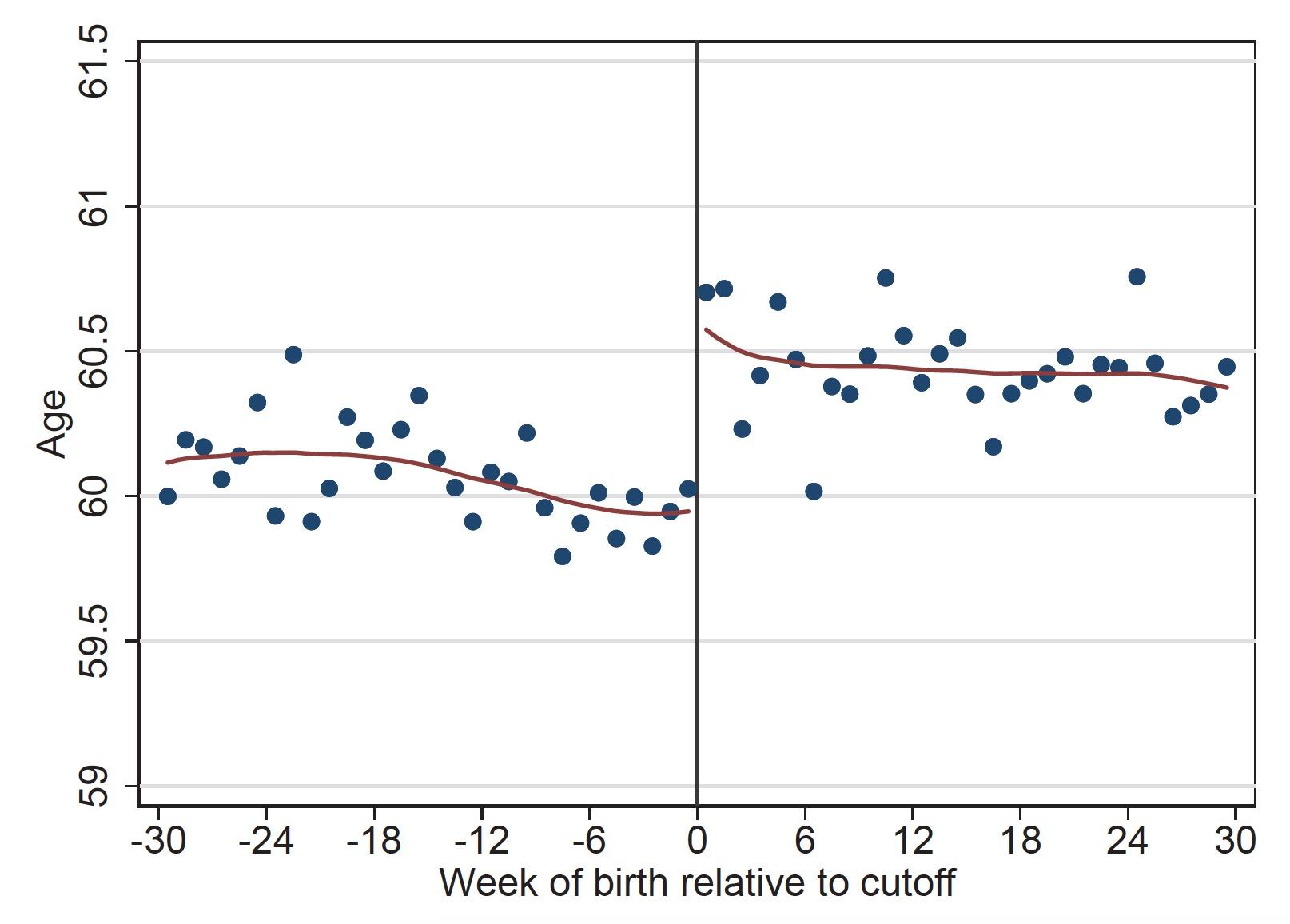

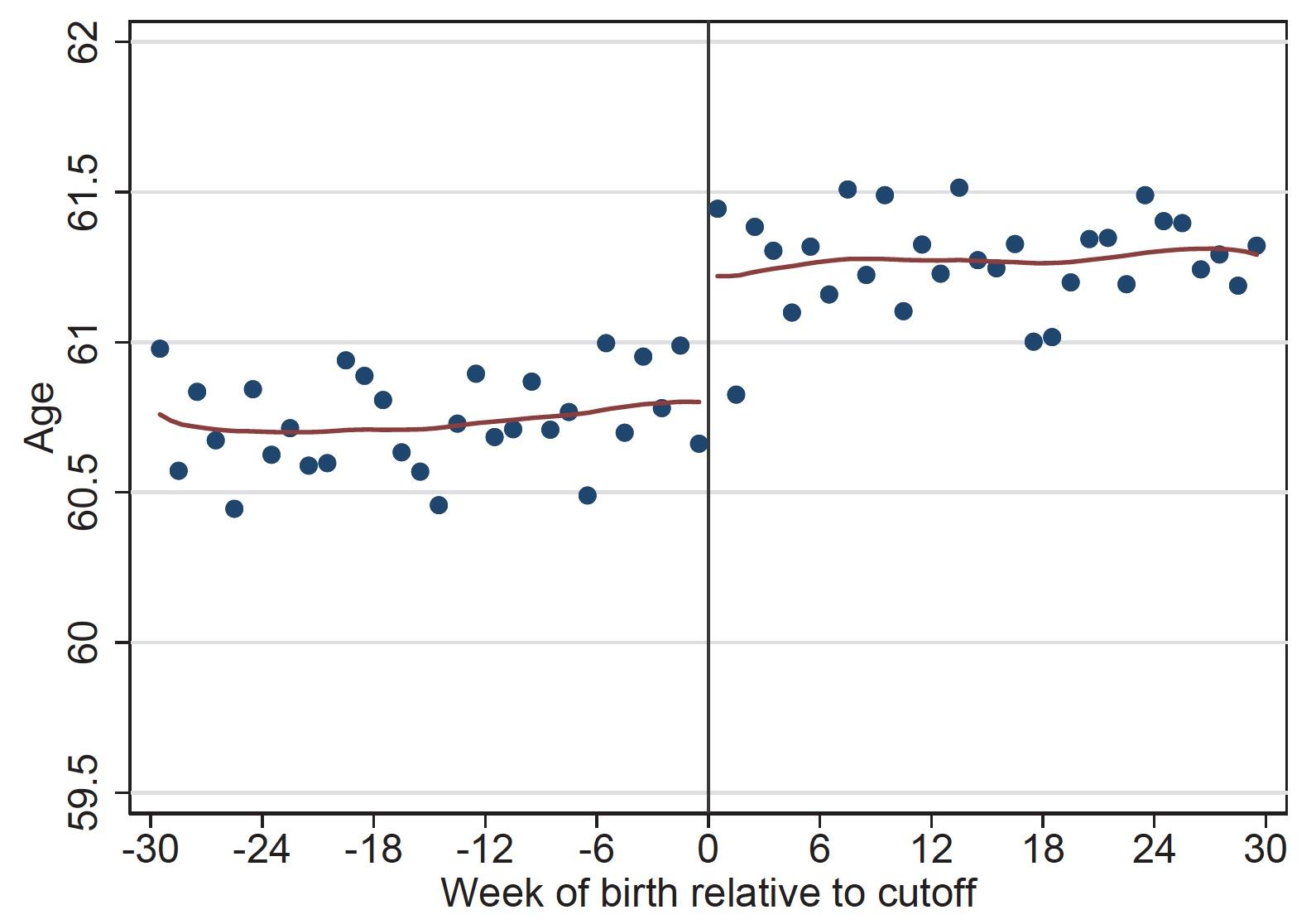

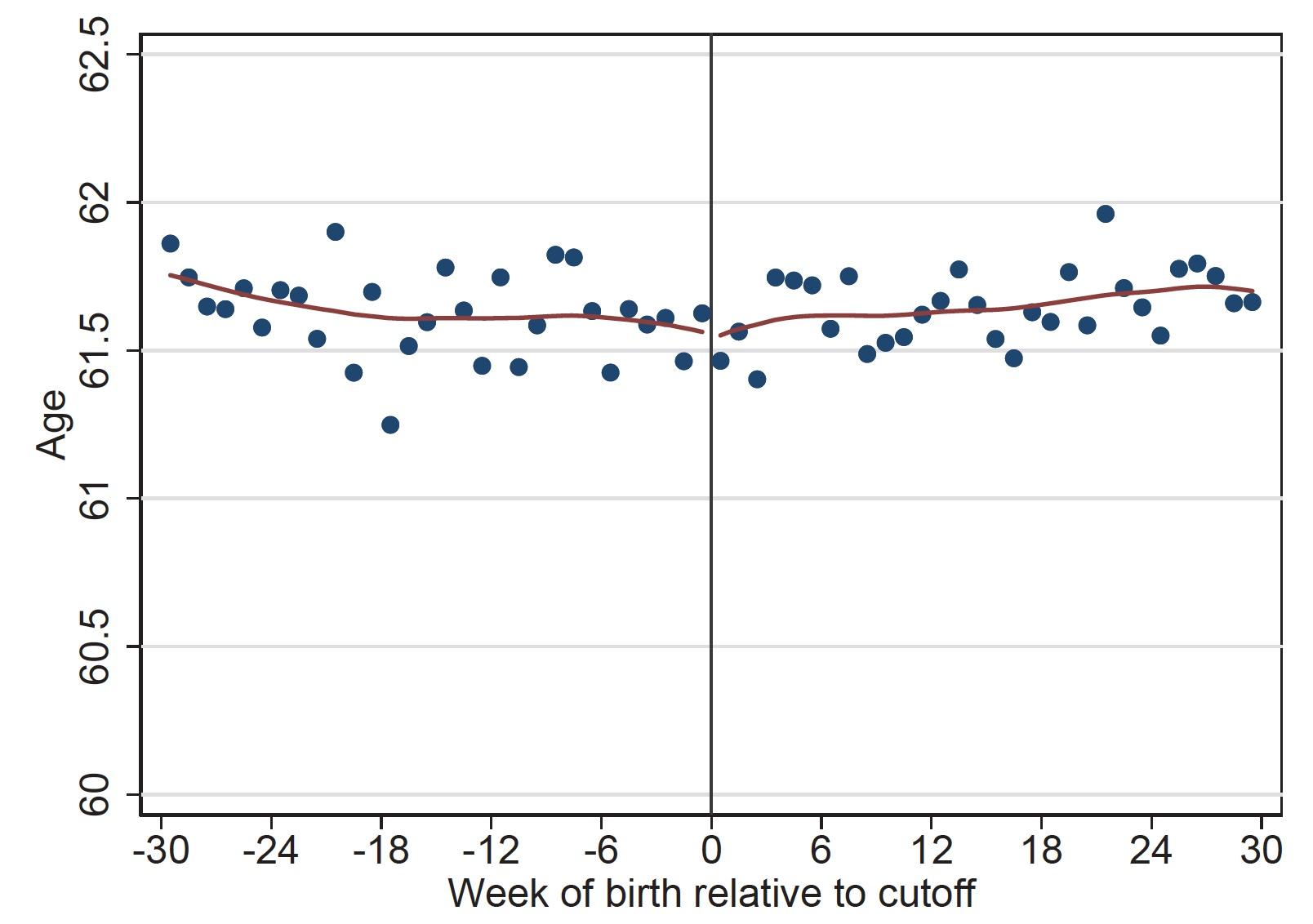

Figure 3 Retirement behaviour around the discontinuity

a) First reform stage

b) Second reform stage

c) Third reform stage

Increasing the full retirement age and offering cheap early claiming delay labour-market exit by 5-7 months, while making early claiming less attractive has no effects on labour market exit. The results are at odds with what standard theory would predict. The average Swiss woman would find it optimal to claim early in the first two reform stages; yet, we observe a large shift in claiming age to the new full retirement age and a smaller increase when financial incentives actually dictate delayed claiming in the third stage.

Further, while some labour-market response is not surprising (the reform mechanically reduced social security wealth, meaning many individuals would choose to work longer in response), the sharpness of the delay in exit is. We would expect a much smoother response to the reform in the first two stages if individuals were making decisions as standard theory predicts.

The results suggest that some people – likely, most people – behave in ways that are inconsistent with what the standard life-cycle model of behaviour would predict. They leave money on the table by delaying the claiming of benefits to an age beyond that which would maximise social security wealth. What this means in this context is that since the reform frames the benefit schedule so that benefits for claims before the full retirement age are ‘penalised’, individuals are averse to early claiming because of the psychological cost it imposes upon them.

We conducted a survey of 1,223 Swiss women between ages 60–65 using a representative internet panel of the Swiss population to determine whether reference dependent preferences were an important force for shaping decisions around pension claiming and retirement. The survey revealed that the most important reason Swiss women claim when they do is that “it seems natural” to start their pension at the individual’s claiming age. Respondents also wanted to “avoid getting a reduced pension” by claiming early. Both responses support the idea that reference dependence together with loss aversion are the dominant reasons that many individuals do not claim at the age that maximises lifetime wealth.

A major competing explanation for the patterns we observed is that making the optimal claiming decision requires a substantial amount of information and attention, and that claiming at the full retirement age is just the simplest option. The fact that individuals who don’t submit the paperwork, to indicate they’d like to claim early, claim at the full retirement age by default makes this a particularly important alternative explanation.

But perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the survey also revealed that most women do seek information, whether from a financial adviser or friends and family and do spend time thinking about the decision. Moreover, the hassle associated with claiming at an age other than the full retirement age was not cited as an important factor.

We are not the first to find that individuals do not respond to public policy reforms in the way that standard economic models predict. In domains ranging from retirement savings (Madrian and Shea 2001) to consumption tax (Chetty et al. 2009), economists continue to find ways in which the neo-classical model fails to explain the way that individuals make decisions in response to policy changes.

And yet, without an understanding of how individuals will respond to policy reform, designing the ‘optimal’ policy is a fool’s errand. As we show, the majority of individuals in our data do not claim their pension benefits at the age that the standard model of behaviour would predict, a finding which should give pause to policymakers who have the standard model in mind when designing policy.

Nominal pension claiming ages (full retirement ages) are an effective tool for governments who wish to ease the burden on strained social security systems. As we show in the paper, much of the government savings from the reform are a consequence of suboptimal responses to nominal raises of full retirement age and not to the financial penalties themselves.

Then, on the one hand, governments can exploit the reference dependence that individuals seem to exhibit by simply nominally increasing the full retirement age, at significant cost to these pensioners. Such a reform effectively redistributes wealth from reference dependent individuals to others. If society places equal (or higher) weight on the welfare of reference dependent individuals, then the system should be actuarially fair.

References

Behaghel, L and D M Blau (2012), “Framing social security reform: Behavioral responses to changes in the full retirement age”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(4): 41–67.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman, S Leth-Petersen, T H Nielsen and T Olsen (2014), “Active vs passive decisions and crowd-out in retirement savings accounts: Evidence from Denmark”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(3): 1141–219.

Lalive, R, A Magesan and S Staubli (2020), “The impact of social security on pension claiming and retirement: Active vs passive decisions”, working paper.

Madrian, B C, and D F Shea (2001), “The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(4): 1149–87.