Many social scientists are interested in the longer-term effects of socio-political upheavals on economically relevant preferences such as trust and trustworthiness. Trust and trustworthiness are often regarded as important contributors to social capital, which helps to “improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions” (Putnam 1993). Societies with less trust and trustworthiness tend to be less coherent and less stable, which may in turn affect long-term economic performance (Nunn 2008). Because of the importance of this topic, economists have investigated what factors affect the level of trust and trustworthiness in a society. In recent years, some studies have found that experience of wars or other conflicts in the society generates distrust and other anti-social behaviour (Fehr 2009, Nunn and Wantchekon 2011), while others have emphasised how war or violent experience can foster pro-social behaviour (for a detailed review, see Bauer et al. 2016).

The contradictory findings may, to a large extent, be related to the nature of the violence or the conflicts experienced. In general, if trauma occurred due to intra-group conflict, trust in others is reduced as ‘betrayal aversion’ comes into effect (Bohnet et al. 2008, Fehr 2009). On the other hand, if the trauma was brought about by inter-group conflict, the within-group bond strengthens and individuals become more cooperative within that group.

In a recent paper on the Cultural Revolution and its intergenerational behavioural impact (Booth et al. 2018), we investigate how this large-scale political upheaval has affected the behaviour of children and grandchildren of those who were mentally or physically abused during the Cultural Revolution, as compared to those who otherwise participated in the Cultural Revolution but were not directly abused.

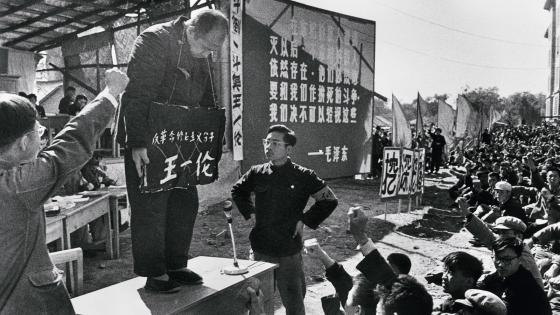

The Cultural Revolution: A major within-group conflict

The Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966 and ended ten years later, was the longest lasting political upheaval in the history of the Chinese Communist Party and had the most pervasive impact on contemporary Chinese communities. During the Cultural Revolution, authorities at different levels were challenged and then removed. Moreover, their representatives (government and Communist Party leaders), together with intellectuals, scientists, and artists as well as people who were deemed to be counter-revolutionaries, were openly criticised, denounced, physically tortured and emotionally humiliated. Many were killed and many committed suicide. There are no official statistics recording ‘unnatural’ mortality and the number of people otherwise affected during the Cultural Revolution. Unofficially, the estimates place the death toll at around 1.1 to 7 million and the number of direct victims of some form of political persecution between 11 to 30 million (Yang 2013, Walder 2014). During the first few chaotic years of the Cultural Revolution, perpetrators of mistreatment were in general former colleagues, subordinates, or neighbours. In some cases even friends, relatives, and family members were directly involved. It therefore represents a major within-group conflict.

The Cultural Revolution was a traumatic experience that extended to everybody in all age groups. Previous economic studies of the impact of the Cultural Revolution mainly focus on events that affected society or certain cohorts as a whole, including large-scale schooling interruptions in urban areas and the sent-down youth movement, which assigned hundreds of thousands of urban middle- and high-school graduates to rural China during the Cultural Revolution. Yet, to our knowledge, no economic study apart from ours examines the long-run effects on children or grandchildren of those who directly experienced the denunciation, torture, humiliation and social isolation during the Cultural Revolution.

Intergenerational behavioural effects of the within-group conflict

Our study is based largely on a suite of laboratory experiments we conducted in Beijing in 2015, in order to elicit our subjects’ preferences for risk, trust, trustworthiness and competition using games widely used in the experimental literature. The details of the experiment are given in full in Booth et al. (2018). We also complemented our analysis from these laboratory experiments with statistical analysis of two large-scale household survey datasets, the China General Social Survey 2003 and the China Family Panel Survey 2012.

In the experiment, we included a module in the exit-survey questionnaire specifically asking people whether their parents and/or grandparents during the Cultural Revolution experienced one or more of seven different types of ill-treatment, humiliation, torture, or political persecution. This information is then used to identify individuals whose parents/grandparents were directly affected and the degree of the effect. We find that those whose parents/grandparents experienced some types of mistreatment during the Cultural Revolution are less trusting, less trustworthy, and less likely to be competitively inclined relative to their peers whose parents/grandparents were not directly mistreated, but experienced the Cultural Revolution nevertheless.

We further investigated whether the correlations we observed between mistreatments of parents/grandparents during the Cultural Revolution and their children/grandchildren’s lack of trust, trustworthiness, and competitiveness are causal relationships or simply an artefact. By artefact, we mean that those mistreated during the Cultural Revolution might have been a special group of people more likely to have the above mentioned behavioural traits, and those traits might have been transmitted to their offspring with or without their mistreatment due to the Cultural Revolution. To this end, we utilised three different methods.

First, we employed the Altonji et al. (2005) and Oster (forthcoming) style of test by adding a very rich set of parental controls. The idea of the test is simple. If our results do not change much after controlling for the rich additional parental characteristics, this suggests that the link between children/grandchildren’s traits is not related to these characteristics of their parents. Thus, it is indicative that the observed correlation may not be linked to mistreated parents/grandparents during the Cultural Revolution who are characterised by lack of trust, trustworthiness and lower competitiveness to start with, but it was instead the mistreatment during the Cultural Revolution that made them so. Our results confirm this.

Second, using large-scale survey data, we conducted a differences-in-differences analysis, in which we identified individuals who were in their developmental age during the first three years of the Cultural Revolution as being in the Cultural Revolution cohort, and those born afterwards as being in the non-Cultural Revolution cohort. Within each cohort, we also identified those whose parents were party members and were working as government official or intellectuals when they were young. As we indicated above, government officials and intellectuals were the main target of the Cultural Revolution. Using differences-in-differences between the Cultural Revolution and non-Cultural Revolution cohort and those whose parents were the targeted group of the Cultural Revolution and those whose parents were not, we investigate if those whose parents were more likely to be mistreated during the Cultural Revolution were less trusting. Our results confirm this was the case.

Third, we utilised a special feature in the exit survey of our lab experiment to examine whether individuals whose grandparents were mistreated during the Cultural Revolution but who themselves had no direct contact with their grandparents had similar behavioural traits as their counterparts who had contact with grandparents. The answer to this question is no. This suggests that the intergenerational transmission of anti-social traits is not due to genetics (nature), but to role-model effects (nurture).

To conclude, we note that our findings of the intergenerational behavioural effect of the Cultural Revolution should be regarded as lower-bound estimates. The Cultural Revolution affected everybody in society. It affected not only people who were mistreated during the Cultural Revolution (our treatment group) but also those in the control group who witnessed the untrustworthy behaviour of their neighbours and friends even though these behaviours were not directed at them. This should affect their behaviour too. Our finding of statistically significant differences in behaviour traits between the treated and control groups indicates that such society-wide experience had a much stronger impression on those who bore the brunt. But it should not be forgotten that this is not the only group that was affected.

References

Altonji, J G, T E Elder and C R Taber (2005), “Selection on observed and unobserved variables: Assessing the effectiveness of Catholic schools”, Journal of Political Economy 113(1): 151-184.

Bauer, M, C Blattman, J Chytilova, J Henrich, E Miguel and T Mitts (2016), “Can war foster cooperation?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3): 249-274.

Bohnet, I, F Greig, B Herrmann and R Zeckhauser (2008), “Betrayal aversion: Evidence from Brazil, China, Oman, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States”, American Economic Review 98(1): 294-310.

Booth, A and X Meng (with E Fan and D Zhang), (2018), “The intergenerational behavioural consequences of a socio-political upheaval”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13354.

Cassar, A, P Grosjean and S Whitt, “Legacies of violence: Trust and market Development”, Journal of Economic Growth 18(3): 285-318.

Fehr, E (2009), “On the economics and biology of trust”, Journal of the European Economic Association 7(2-3): 235-266.

Nunn, N (2008). “The long-term effects of Africa’s slave trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(1): 139-176.

Nunn, N and L Wantchekon (2011), “The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa”, American Economic Review 101(7): 3221-52.

Oster, E (forthcoming), “Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Business Economics and Statistics.

Putnam, R (1993), Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy, Princeton University Press.

Walder, A G (2014), “Rebellion and repression in China, 1966–1971”, Social Science History 38: 513-539.

Yang, J (2013), “Path, theory, and institution: My reflection on the Cultural Revolution”, Remembrance (in Chinese) 104: 2-23.