Editors' note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the VoxEU ebook, Brexit Beckons: Thinking ahead by leading economists, available to download free of charge here.

In 2003, when assessing whether the UK should join the European single currency, one of Gordon Brown’s five economic tests was: “What impact would entry into European monetary union have on the competitive position of the UK’s financial services industry, particularly the City’s wholesale markets?”1 The financial sector was the only industry singled out for specific consideration when considering making a major step toward greater European integration.

The reason that the financial industry got such attention is that the City of London, the name given generally to the UK’s financial markets and the industry that goes with them, is an important part of the UK economy and a leading global financial centre:2

- The sector generates a substantial share of UK economic activity.

Although only accounting for 3.4% of UK workforce jobs, financial and insurance services account for 8% of UK gross value added (2013 figures taken from ONS 2015).

- The sector generates a large trade surplus.

Financial services together with insurance and pension services ran a £58 billion trade surplus in 2014 (+3.2% of GDP). This helped to offset the trade deficits run by other sectors such that the overall trade deficit was £34.5 billion (-1.9% of GDP).

- The sector is an important source of tax revenue – about 11% of the national total.

The financial sector accounted for £7.6 billion of corporation tax in the tax year ending in March 2015; this represents 17.7% of the total corporation tax collected. The Bank Levy, employers’ NIC, irrevocable VAT, stamp duties, and other taxes borne by the financial sector raised an additional £15.9 billion. The sector also collects PAYE income tax and employee NIC from its employees, as well as other taxes.

Altogether the total tax revenue borne, or collected, by the financial services sector in the 2014-2015 tax year is estimated to be £66.5 billion, or 11% of total UK tax revenue.3This amounts to just over £1.2 million of tax revenue per week.

Success of UK financial services

There are many reasons for the success of the UK financial services industry. As well as the legal system, the English language, and the established complementary services industries, there is a particularly important role for the labour market. The UK’s labour regulations are more flexible than those of many other EU countries, which makes it easier for UK firms to adjust their workforce more cheaply. And there is a large pool of skilled labour already working in UK financial services, which make it attractive as a location for financial services firms to establish themselves.

But EU membership also plays a major role. Related to the labour market, a large number of the skilled financial workers in the UK industry are EU nationals who can freely migrate to the UK to provide their scarce skills into this important industry. More directly, EU membership grants UK financial services firms the right to conduct business anywhere in the 27 other EU countries; the so-called ‘passporting rights’.

Passporting rights and the implications of Brexit

To understand the issue of passporting rights and Brexit, we need to consider two things. First, we need to examine the amount of UK financial services activity that relies on passporting rights. Second, we need to consider what might happen to passporting rights under Brexit.

The now-resigned British EU Commissioner responsible for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union, Lord Hill, has pointed out the benefits of passporting rights for the UK financial services industry:4

- British banks made over €1,000 billion of loans, and took a similar amount of euro deposits;

- The EU-regulated investment funds, “Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities” (UCITS), worth around €8,000 billion, can be managed by UK-based firms generating service fees and returns in the UK;

- Insurance and reinsurance firms do not need to undergo any equivalence assessment before providing their services across the EU;

- As a result of these benefits, half the world’s financial firms have chosen to base their European headquarters in the UK.

Additionally, UK-based banks were able to benefit from access to the ECB’s liquidity operations during the recent financial crisis period.

The effect of the Brexit vote on the UK financial services sector is highly uncertain as it ultimately depends on the negotiated deal. As a general case, I don’t think other EU countries will want to be seen to allow the UK to choose the benefits it wants without the other aspects of membership (such as free movement of labour). And specific to financial services, some countries in the EU covet the large share of EU financial services that the UK has and will hope to be able to make their own country relatively more competitive.

Each of the broad models put forward as potential options for the UK entails different outcomes for passporting and financial services:

Norwegian financial services have passporting rights, so a similar model for the UK would be the least disruptive for the City. Of course, this deal involves contributions to the EU budget and free movement of labour, which would seem to be part of the major objections to EU membership. Hence it is not clear it will be either offered, or would be accepted by the UK.

- The Swiss model (or Canada deal)

The deal that Switzerland has with the EU does not grant their financial institutions access to the EU market. The same is true for the (as yet unsigned) Canadian trade agreement.

Without a new agreement, or with an agreement to default the UK to WTO status, the banks would naturally lose their passporting rights.

In the case of the ‘no passporting rights’ outcomes, there would be new restrictions on cross-border business for UK-based financial firms. If the EU were to agree that UK standards are equivalent to those in the EU, then financial services could still be provided into the EU. This status may mean firms have to set up subsidiaries in the EU (with the associated costs including capital requirements) and the extent to which EU regulators would easily allow firms continue to carry out the transactions from London while booking them through a subsidiary in the EU is unclear; some substantial operations in the passport country will be required.5 Without this equivalence status, the costs of continuing to carry out EU business out of London are even higher.

Economists’ assessments of these issues and the costs of Brexit

I believe that the UK will still have a relatively large and active financial system in the years ahead. Nonetheless, I also think that there are significant costs for the sector arising from Brexit. As argued above, part of the attraction of the UK’s financial markets is its status as a major financial centre in the EU. The vote to leave the EU has cast doubt on this status and while I don’t expect that many banks or other financial institutions will simply up and leave in the coming months, their marginal expansion and hiring decisions may lean toward EU member states for some of their operations. Over time, this will erode the overall size and importance of the UK financial markets. And the dynamics of agglomeration effects are such that the more firms move out, the greater the incentive for others to follow.

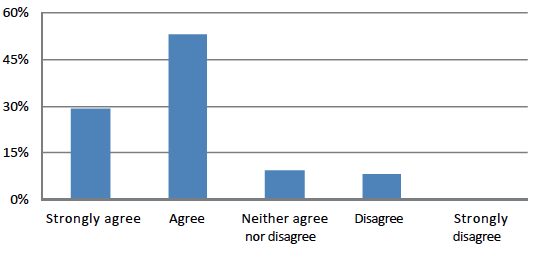

Most economists agree that there will be a negative impact on the UK financial sector. In June 2016, before the Brexit vote, the Centre for Macroeconomics survey of academic economists in the UK asked: “Do you agree that there would be substantial negative long-term consequences for the UK financial sector if the UK were to leave the EU?”6 The responses, weighted by self-assessed confidence, are reproduced in Figure 1. In a highly unusual situation of agreement amongst economists, 82% of the 38 respondents either strongly agreed or agreed; a mere 8% disagreed.

Figure 1 Confidence-weighted responses to the June 2016 CfM survey question: “Do you agree that there would be substantial negative long-term consequences for the UK financial sector if the UK were to leave the EU?”

My view of the costs is relatively sanguine compared to some of the economics profession. Ray Barrell of Brunel University London responded to the CfM survey saying, “[t]he UK financial sector is likely to suffer significantly if we leave the EU”. He stressed the loss of passporting rights and the likelihood that the ECB will work to ensure that it has regulatory control over the whole single market in financial services. Richard Portes of London Business School and CEPR mentioned similar points and felt that “[m]any activities and much financial sector employment would go to Frankfurt, Paris, and Dublin - Edinburgh as well, if Scotland were then to secede”. Separately to the CfM survey, Anil Kashyap of the University of Chicago believes that the UK financial sector will “shrink and shrink substantially”.7

Concluding remarks

Returning to the five tests conducted to assess UK adoption of the euro, it is noteworthy that the financial services test assessed that while the UK’s wholesale and retail financial markets would remain strong whether inside or outside EMU, EMU entry would likely enhance their position.8 It was the only one of the five tests that was met successfully. And now the UK is embarking on a period of finding out how costly taking a large step back from the EU is going to be for the sector.

Unless the politicians conducting the Brexit negotiations do their utmost to limit the damage, the loss of passporting rights, and initially simply the uncertainty concerning such market access, is likely to have a significant negative impact on the UK financial sector. Given the importance of this sector to the UK economy, this would contribute to an economic weakening in the UK.

References

Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2015), The Blue Book: 2015 Edition.

PwC (2015), Total Tax Contribution of UK Financial Services (Eighth Edition), Report for the City of London Corporation.

Endnotes

[1] http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/documents/international_issues/the_euro/assessment/report/euro_assess03_repintro.cfm

[2] In fact, the Global Financial Centres Index has rated London as the world's most competitive financial centre for the past two years. It should be noted that Edinburgh also has a large financial sector.

[3] The figures are a combination of official statistics and estimates by Pricewaterhouse Coopers for a report for the City of London Corporation (PwC 2015).

[4] http://ec.europa.eu/commission/2014-2019/hill/announcements/commissioner-hills-speech-chatham-house-royal-institute-international-affairs_en

[5] https://next.ft.com/content/52d968b0-3a52-11e6-9a05-82a9b15a8ee7.

[6] The full discussion of survey results is available at http://cfmsurvey.org/surveys/brexit-potential-financial-catastrophe-and-... and http://www.voxeu.org/article/cfm-survey-june-2016-brexit-and-city.

[7] Views expressed at the NBER Summer Institute discussion, “Brexit: Likely Effects of Britain's Departure from EU on Trade, the U.K., and European Integration” (video available at www.nber.org).

[8] http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130129110402/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/euro_assess03_repexecsum.htm.