The creation of ideas is crucial for scientific progress, technological innovation, and economic development, particularly in a world where “knowledge has taken over much of the economy” (The Economist 2000). As argued by many scholars (e.g. Arrow 1962, Mokyr 2002), one of the major inputs in the creation of new ideas is existing knowledge. Most famously, Isaac Newton stressed the importance of existing knowledge in his letter to Robert Hooke:

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” (Newton, 1675)

The quote not only emphasises that scientists build on existing knowledge to produce new ideas, but also that knowledge produced by scientific ‘giants’ – that is, frontier knowledge – is particularly important. Access to existing knowledge not only fuels basic scientific progress, but is also key for the development of new technologies, as emphasised by theoretical models of economic growth (e.g. Romer 1986, Romer 1990, Jones 1995, Weitzman 1998).

As shown in Figure 1, scientific articles that cite frontier research are more likely to become a ‘hit’ (i.e. to end up in the top 1% of the long-run citation distribution).

Figure 1 Probability of hit paper depending on cited references

Notes: The figure plots the probability that a paper becomes a ‘hit’, i.e., ends up in the top 1% of the field-level citation distribution until today, depending on the quality of cited references. Only references to research published in the five years preceding the publication of the citing paper are considered. Self-citations are excluded. The bar ‘at least one top 1% reference’ shows the probability that the citing paper becomes a hit if it cites at least one reference that ends up in the top 1% of the citation distribution until today. The bar ‘at least one top 3% reference’ shows the probability that the citing paper becomes a hit if it cites at least one reference that ends up in the top 3% of the citation distribution, and so on. The bar ‘no frontier reference’ shows the probability that the citing paper becomes a hit if it does not cite references that end up in the top 5% of the citation distribution.

While Figure 1 shows that citing the research frontier is correlated with writing hit papers, it is not clear whether access to the research frontier has a causal effect on the production of high-quality ideas. The correlation could be motivated by networks of highly productive scientists, who mostly cite each other’s research, such as the physicists who advanced the quantum revolution in the 1920s and 1930s. Because of this and other endogeneity concerns, researchers have not been able to empirically isolate the causal effect of frontier knowledge on the creation of ideas.

To overcome these challenges, we study a dramatic decline in international scientific cooperation that occurred during WWI and the first post-war years – the ‘boycott of Central scientists’ (Iaria et al. 2018).

A shock to international scientific collaboration

With the beginning of WWI, the world split into the Allied (UK, France, later the US, and a number of smaller countries) and Central (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria) camps. The involvement of scientists in the war effort, in particular in the development of chemical weapons, and the extremely nationalistic stance taken by many in support of their homeland pitted the opposing scientific camps against each other.

Allied scientists were suddenly cut off from their peers in Central countries – in particular from Germany, a country whose scientists had received more than 40% of Nobel prizes in physics and chemistry in the pre-war period. Similarly, Central scientists were cut off from their peers in Allied countries – in particular from the UK (20% of Nobel prizes), France (15% of Nobel prizes), and the US, the rising scientific superpower. This schism of the scientific world persisted during the post-war years because Allied scientists organised a boycott against Central scientists, to punish them for their involvement in the war effort. The boycott was strongest in the first years after the war and lasted until 1926.

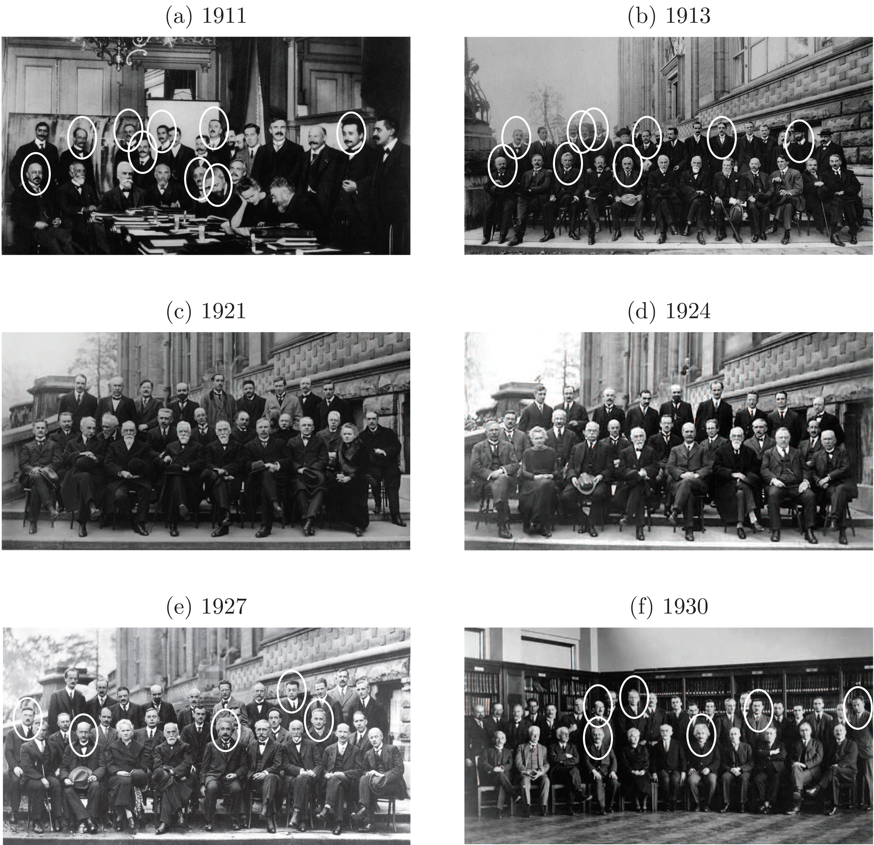

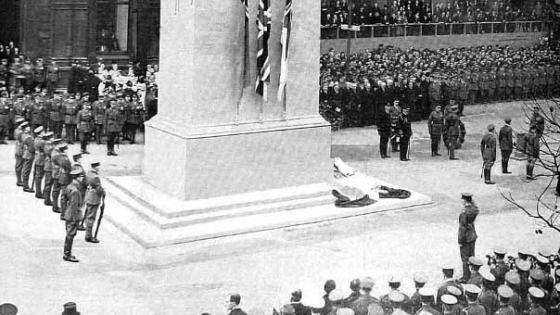

We document that the delivery of international journals was severely delayed and that international conferences were cancelled or only involved scientists from one of the warring camps (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Central scientists at the Solvay Conferences in Physics

Notes: The figure gathers historical pictures of delegates at the Solvay Conferences in Physics. Circles indicate delegates from Central countries. The first Solvay Conference was organised in 1911 and was attended by the leading physicists of the time, including Marie Curie, Ernest Rutherford, Max Planck, and Albert Einstein. In that year, nine of the 24 participants came from Central countries. In 1913, nine of the 31 participants came from Central countries. During the war, the Solvay Conferences were discontinued. The first post-war conference took place in 1921. Scientists from Central countries were not invited. Nor were they invited to the 1924 conference. By 1927, the boycott had ended and five of the 30 participants came from Central countries. The 1927 conference is possibly the most famous scientific conference ever organised. It took place at the height of the quantum revolution, and 17 of the 30 participants were current or future Nobel Laureates. In 1930, six of the 36 participants came from Central countries. For more details see Iaria et al. (2018).

Measuring the interruption of international knowledge flows

We show that WWI and the following boycott against Central scientists severely interrupted international scientific cooperation (Iaria et al. 2018). After the onset of WWI, papers cited relatively less research from outside the camp, compared to research from home (Figure 3, red solid line). Similarly, papers cited less research from foreign countries inside the camp, but this decline was markedly smaller (Figure 3, blue dashed line). Importantly, this decline in international citations not only affected average quality research, but also research at the scientific frontier.

Figure 3 Decline in international citations

Notes: The ‘Foreign outside camp’ line measures citation shares to research from outside the camp, relative to research from home. The ‘Foreign inside camp’ line measures citation shares to research from foreign scientists inside the camp, relative to research from home. Only citations to recent research are considered (i.e., research published in the preceding five years). For example, the first dot (1905) measures relative citation shares to research published between 1901 and 1905. The second dot (1906) measures relative citation shares to research published between 1902 and 1906, and so on. For more details see Iaria et al. (2018).

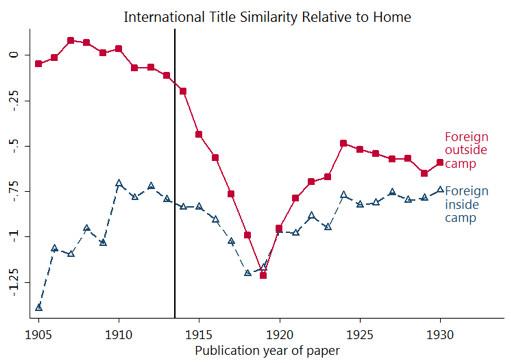

We also investigate whether the collapse in international scientific cooperation affected the direction of research in the opposing scientific camps. Using the machine-learning technique Latent Semantic Analysis, we document that the similarity to papers from outside the camp fell sharply after the onset of WWI and then slowly recovered during the 1920s (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Decline in similarity of papers

Notes: The vertical axis measures the standardised (mean 0 and standard deviation 1) Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) title similarity to papers by scientists from home, foreign countries inside the camp, and foreign countries outside the camp. The ‘Foreign outside camp’ line measures the LSA title similarity to papers from outside the camp, relative to papers from home. The ‘Foreign inside Camp’ line measures the LSA title similarity to papers from foreign scientists inside the camp, relative to papers from home. Only title similarity to recent papers is considered (i.e., papers published in the preceding five years). For example, the first dot (1905) measures relative title similarity to papers published between 1901 and 1905, and so on. For more details see Iaria et al. (2018).

Effects on scientific production and technological applications

In the second part of our paper, we show that reduced international scientific cooperation led to a decline in the production of basic science and its application in new technology.

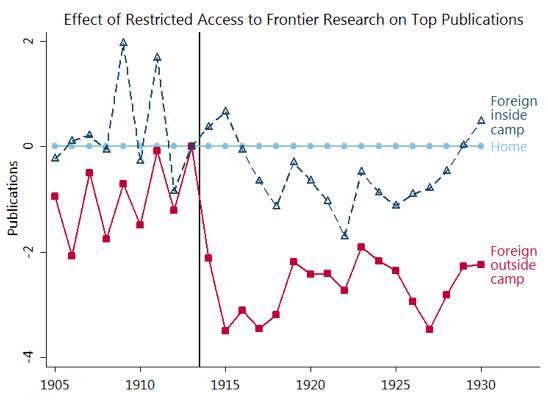

We compare productivity changes for scientists who, in the pre-war period, relied on frontier research from abroad to changes for scientists who relied on frontier research from home. After 1914, scientists who relied on frontier research from abroad, and who were now suddenly cut-off from the research frontier, published fewer papers in top scientific journals (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Changes in productivity of scientists reliant on frontier research from home, from foreign countries inside the camp, and from foreign countries outside the camp

Notes: The ‘Foreign outside camp’ line measures changes in yearly top publications for scientists who, in the pre-war period, relied on frontier research from outside the camp, compared to scientists who relied on frontier research from home. The ‘Foreign inside camp’ line measures changes in yearly top publications for scientists who, in the pre-war period, relied on frontier research from foreign scientists inside the camp, compared to scientists who relied on frontier research from home. Pre-war reliance on frontier research is measured by pre-war citations to frontier research at the field-country pair level. For more details see Iaria et al. (2018).

In further results we also show that the interruption of international knowledge flows led to stark declines in the production of research that was worthy of a Nobel Prize nomination. Furthermore, scientists introduced fewer novel scientific concepts, as measured by the introduction of novel scientific words (e.g. magnetron or electroencephalogram). We also show that the reduction in the production of basic scientific knowledge affected the development of new technologies. Scientific fields that were suddenly cut off from the research frontier produced fewer scientific concepts that were used in patents. Thus, reductions in the output of basic science also had a negative effect on the development of new technologies.

Implications for science and innovation policy

These results show that access to frontier research is key for the production of ideas, including path-breaking ones. Facilitating access to frontier research can therefore substantially increase the production of basic science. Access to the knowledge frontier needs to be interpreted in a broad sense – not only physical access to journal articles, conferences, and research seminars, but also discerning the thin, ever-advancing, and truly path-breaking edge of the frontier from the millions of scientific papers published every year. Science policy should be geared towards the facilitation of access and capitalising on the potential catalytic effects of frontier research in enhancing scientific progress. Providing open access to journals may partly achieve this goal. However, discerning what constitutes frontier research requires skills that are hard to develop without guidance from leading scientists working at the forefront of scientific endeavour. Personal contacts are particularly useful because face-to-face interactions are a superior way of transmitting ideas (e.g. Glaeser 2011, Head et al. 2015). High-quality PhD programs at universities where frontier research proliferates can therefore help to put young scientists on the most-promising career paths (Waldinger 2010). Even more established scientists can profit from long-term and short-term visits at the centres of science (Catalini et al. 2016) and from attending high-quality conferences (de Leon and McQuillin 2015) and research seminars.

Finally, these results show that access to frontier research not only affects the production of basic science, but that it also increases the application of science in the development of new technology. Policies that widen access to frontier research could therefore benefit society beyond the confines of science itself.

References

Arrow, K (1962), “Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention”, in The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity: Economic and Social Factors, Princeton University Press: 609–626.

Catalini, C, C Fons-Rosen and P Gaule (2016), “Did cheaper flights change the direction of science?”, working paper.

de Leon, F and B McQuillin (2015), “The role of conferences on the pathway to academic impact: Evidence from a natural experiment”, University of Kent, mimeo.

Glaeser, E (2011), Triumph of the City: How Urban Spaces Make Us Human, Pan Macmillan.

Head, K, Y A Li and A Minondo (2015), “Geography, ties, and knowledge flows: Evidence from citations in mathematics”, working paper, SSRN 2660041.

Iaria, A, C Schwarz and F Waldinger (2018), “Frontier knowledge and scientific production: Evidence from the collapse of international science”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Jones, C I (1995), “R&D-based models of economic growth”, Journal of Political Economy 103(4): 759–784.

Mokyr (2002), The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy, Princeton University Press.

Newton, I (1675) Letter from Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke.

Romer, P M (1986), “Increasing returns and long-run growth”, Journal of Political Economy 94(5): 1002–1037.

Romer, P M (1990), “Endogenous technological change”, Journal of Political Economy 98(5): 71–S102.

The Economist (2000), “Who owns the knowledge economy?”, 6 April.

Waldinger, F (2010), “Quality matters: the expulsion of professors and the consequences for PhD student outcomes in Nazi Germany”, Journal of Political Economy 118(4): 787–831.

Weitzman, M L (1998), “Recombinant growth”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(2): 331–360.