One of the main lessons from the Global Crisis is that monetary policy, and microprudential regulation and supervision are not enough to achieve financial stability. Initially, this conclusion was mainly considered relevant for emerging markets and low-income countries. But after the crisis, this view has clearly been extended to advanced economies as well. Macroprudential instruments are nowadays considered an important part of the policymaking toolkit to promote financial stability in almost all countries.

Several studies have documented the increasing use of macroprudential measures across countries (e.g. Crowe et al. 2011, Kuttner and Shim 2013, Budnik and Kleibl 2018). Country, time, or instrument coverage has been limited, however. Among the macroprudential datasets, an earlier study of ours currently covers the widest sample of countries (119 over the period from 2000 to 2013, including 12 instruments) (Cerutti et al. 2017). Taking advantage of the IMF’s 2017 Macroprudential Policy Survey (IMF 2018) and other recent sources, we recently updated the sample period to cover 2000–2017, and further expanded the coverage of the dataset to 160 countries, covering the same 12 instruments. Here we summarise how the usage and types of macroprudential measures have changed over recent years and across countries.

The usage of macroprudential policies across country groups and over time

Following Cerutti et al. (2017), the updated dataset aims to only capture usage of macroprudential policies so as to cover as many countries as possible. Specifically, macroprudential instruments are each coded as simple binary measures (i.e. either they were in place, or they were not).[1]An overall macroprudential index is then calculated as the simple sum of the scores for all 12 instruments. The macroprudential instruments covered are: general countercyclical capital buffer/requirement (CTC); leverage ratio for banks (LEV); time-varying/dynamic loan-loss provisioning (DP); caps on the loan-to-value ratio (LTV); debt-to-income ratio (DTI); limits on domestic currency loans (CG); limits on foreign currency loans (FC); reserve requirement ratios in foreign currency (RR); levy/tax on financial institutions (TAX); capital surcharges on systemically important financial institutions (SIFI); limits on interbank exposures (INTER); and concentration limits (CONC).

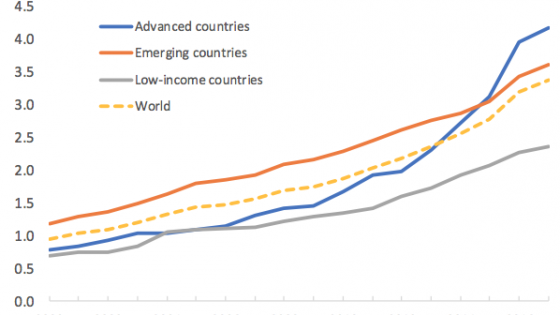

Over the period 2000–2017, most countries have increased their usage of macroprudential measures. As depicted in Figure 1, the average overall usage of macroprudential policies (as captured by the MPI) starts at about one in 2000 and ends at almost 3.5 in 2017. A clear acceleration is visible after the Global Crisis, with countries more than doubling their average usage. This is especially the case for advanced economies, which since 2015 are using, on average, more macroprudential instruments than emerging markets or low-income countries are. In 2017, advanced economies were using on average 4.25 instruments, with emerging markets and low-income countries using 3.5 and 2.5 instruments, respectively. The acceleration in the usage of macroprudential policies is linked to post-crisis reforms that targeted many of the financial sector deficiencies identified as important factors during the crisis (e.g. Basel III, 2016 CRR/CRDIV framework in the EU).

Figure 1 The macroprudential policy index by income group

Usage of individual macroprudential instruments

In terms of individual macroprudential instruments, the database highlights some interesting heterogeneity.

As of 2017, most countries (about 80% of countries in the sample) have implemented concentration limits (CONC). This is followed by SIFI (40%), LTV (36%), INTER (31%), DTI (29%), FC (26%), LEV (23%), TAX (23%), RR (18%), DP (15%), CG (12%), and CTC (1%).

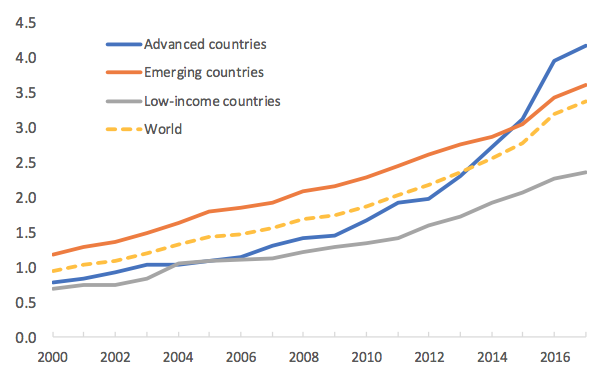

The two borrower-based instruments – LTV and DTI – are used relatively more by advanced countries. As of 2017, as depicted in Figure 2, they are now used in about 64% and 36% of advanced economies, respectively. This heavier usage is related to the adverse lessons these countries experienced from their housing sector vulnerabilities, also connected to the larger share of total credit in the form of mortgages in advanced economies.[2]

Figure 2 Share of countries using specific instruments by income group

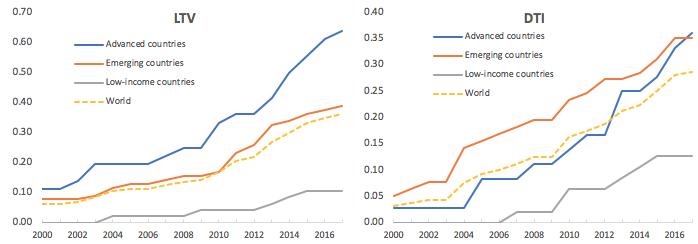

Controls on foreign currency lending (FC), reserve requirements on foreign currencies (RR), and limits on leverage ratios (LEV) are on average used more in emerging markets and low-income countries than in advanced economies, as visible in Figure 3. It relates to the larger foreign currency usage in bank operations in these countries (e.g. associated with euro/dollarization) and to desires to control systemic risks in their relatively more important banking systems.[3]

Figure 3 Share of countries using specific instruments by income group

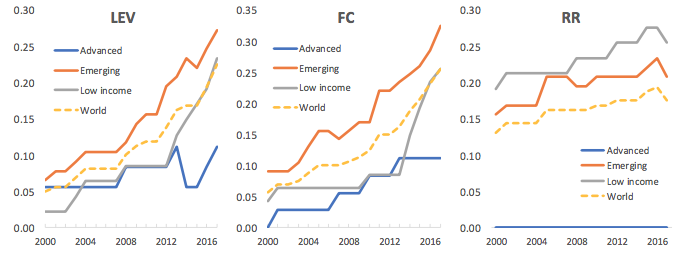

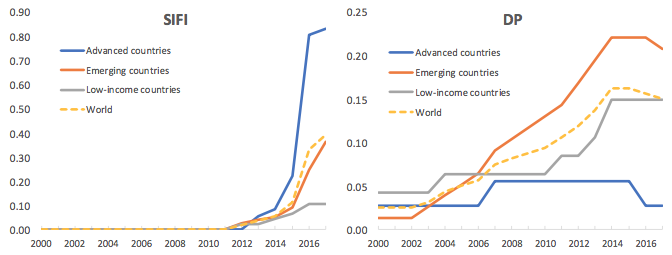

Usage has not followed a homogenous trend across macroprudential instruments. As shown in Figure 4, the steepest increase in usage was for SIFI, mostly the result of international banking regulation frameworks being adopted. On the other hand, there was a decline in the usage of dynamic provisioning (DP) in both advanced economies and emerging markets in recent years.

Figure 4 Share of countries using specific instruments by income group

Will this increasing faith in macroprudential policy pay off?

The post-crisis reforms clearly are associated with generally increasing faith in macroprudential policies. Usage of macroprudential instruments has evolved, with advanced economies now using instruments more than emerging markets and low-income countries. And there have been changes in the relative usage of some instruments, such as a decline of dynamic provisioning. The large and increasing literature on macroprudential policies indicates that several macroprudential policies seem be effective (e.g. many papers have found that LTVs, especially when actively adjusted in intensity over time, are able to affect credit growth and house prices). At the same time, the jury is out on how much macroprudential polices can deliver in terms of overall financial stability. We still do not know how effective these policies will be for financial stability broadly as implementation of many macroprudential instruments is very recent and most countries have not gone through a full economic and financial cycle.4 Further research and better data are also needed in order to understand the interaction of macroprudential policies with other policies (e.g., capital control measures), the best way to implement policies over the cycle (rules versus discretion), their economic costs, and the best way to deal with political economy constraints. This database can help with furthering this research agenda.

Authors’ note: The updated dataset used in this column is available here. We thank Haonan Zhou for superb assistance in the update of the dataset.The views expressed here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Bank for International Settlements, the ECB or the IMF, their Executive Boards, or management.

References

Budnik, K and J Kleibl (2018), “Macroprudential regulation in the European Union in 1995-2014: Introducing a new data set on policy actions of a macroprudential nature,” ECB, Working Paper 2123.

Cerutti, E, S Claessens and L Laeven (2017), “The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: New evidence,” Journal of Financial Stability 28: 203–224 (original and updated datasets are available here).

Cerutti, E, R Correa, E Fiorentino and E Segalla (2017a), "Changes in prudential policy instruments -- A new cross-country database," International Journal of Central Banking 13(1): 477–503.

Cerutti, E, G Dell’Ariccia and J Dagher (2017b), “Housing finance and real estate booms: A cross-country perspective,” Journal of Housing Economics 38: 1–13.

Claessens, S (2015), “An overview of macroprudential policy tools,” Annual Review of Financial Economics 10.1—10.26.

Crowe, C, D Igan, G Dell’Ariccia and P Rabanal (2011), “How to deal with real estate booms,” IMF, Staff Discussion Note 11/02.

IMF (2018), “The IMF’s annual macroprudential policy survey— Objectives, design, and country responses”.

Kuttner, K N and I Shim (2013), “Can non-interest rate policies stabilise housing markets? Evidence from a panel of 57 economies,” BIS, Working Papers No 433.

Endnotes

[1] For a dataset measuring the intensity of usage, see Cerutti et al. (2017a) for a wide cross-country coverage (64 countries) of five instruments.

[2] For more information about mortgage markets across countries, see Cerutti et al. (2017b).

[3] The usage of leverage ratios is expected to increase worldwide as the leverage ratio moves from a monitoring requirement to a limit under Basel III in 2018.

[4] Macroprudential policies can also pursue multiple objectives. The objective of macroprudential policies is often linked to: increasing the resilience of the financial system to shocks (e.g. by building capital buffers); containing the build-up of vulnerabilities over time (e.g., by reducing procyclical feedback between asset prices and credit); controlling structural vulnerabilities arising through interlinkages; and the critical role of individual intermediaries in key markets that can render individual institutions ‘too big to fail.’ See Claessens (2015) for a review.