The Irish economy has periodically been held up as an example that other countries can learn from, but the lessons to be learned have varied over time. Depending on the period, it has served as a model to be followed or a sobering lesson in failure. In 1988 The Economist dubbed it “the poorest of the rich”; by 1997 the same magazine was hailing it as “Europe’s shining light”. In the run-up to the Great Recession the country was “a poster-child for what not to do”; by 2013 it was “setting standards” for how to recover (The Economist 2015, Roche et al. 2016: 1).

Academic accounts of the Irish economy have mirrored the fluctuations in its fortunes and the conventional wisdom of the time. In the late 1980s, the distinguished historian Joseph Lee (1989) concluded that “Irish economic performance has been the least impressive in western Europe, perhaps in all Europe, in the twentieth century;” by the early 21st century the task facing Honohan and Walsh (2002) was to explain “the Irish miracle”.1 As the centenary of Irish independence approaches, a longer-run perspective may be warranted (Ó Gráda and O’Rourke 2021).

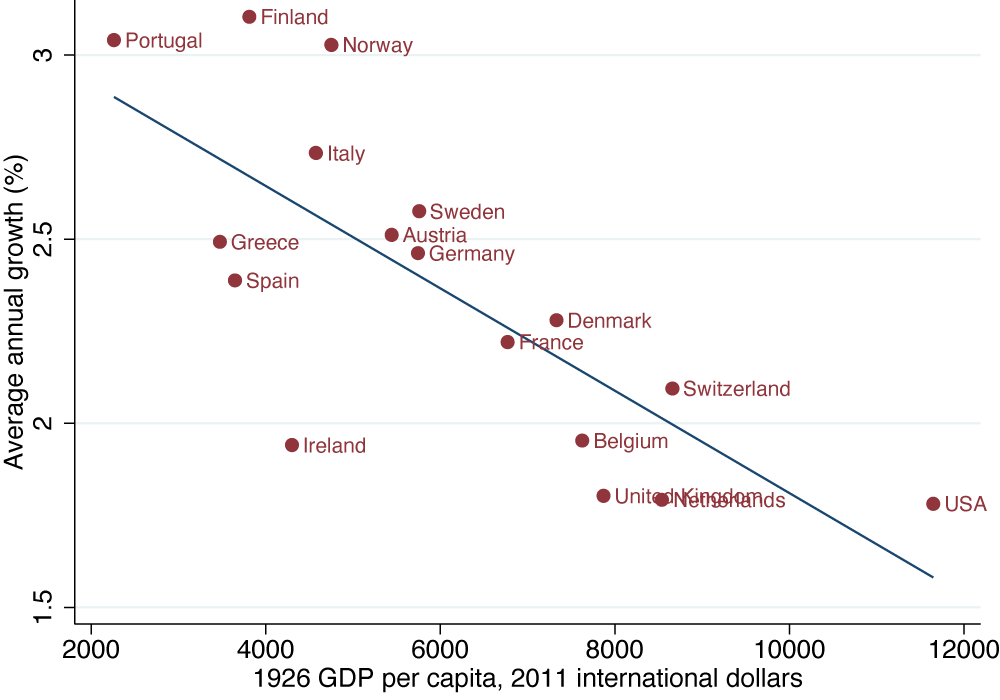

Figure 1 Initial income and subsequent growth, 1926-1988

Source: Ó Gráda and O’Rourke (2021), based on Bolt and van Zanden (2020), data from the Central Statistics Office, and data kindly provided by Rebecca Stuart.

During the first six decades of Irish independence, the country was a striking under-performer, growing much more slowly than a standard unconditional convergence framework would have predicted (Figure 1). At the time that Lee (1989) was writing, his pessimism was fully deserved and widely shared. But economic historians have revised our understanding of the causes and timing of that relative Irish failure. The Economic War with Britain in the 1930s was not as costly as once thought, and may even have been on balance beneficial, given that the settlement of the dispute involved a large write-down of Irish debt and the return to the country of the Treaty Ports. The opportunity costs of protection for a small country like Ireland were much smaller in an era when its main trade partners had already made the switch to protection, and when import-substitution could provide welcome jobs (Clemens and Williamson 2004).

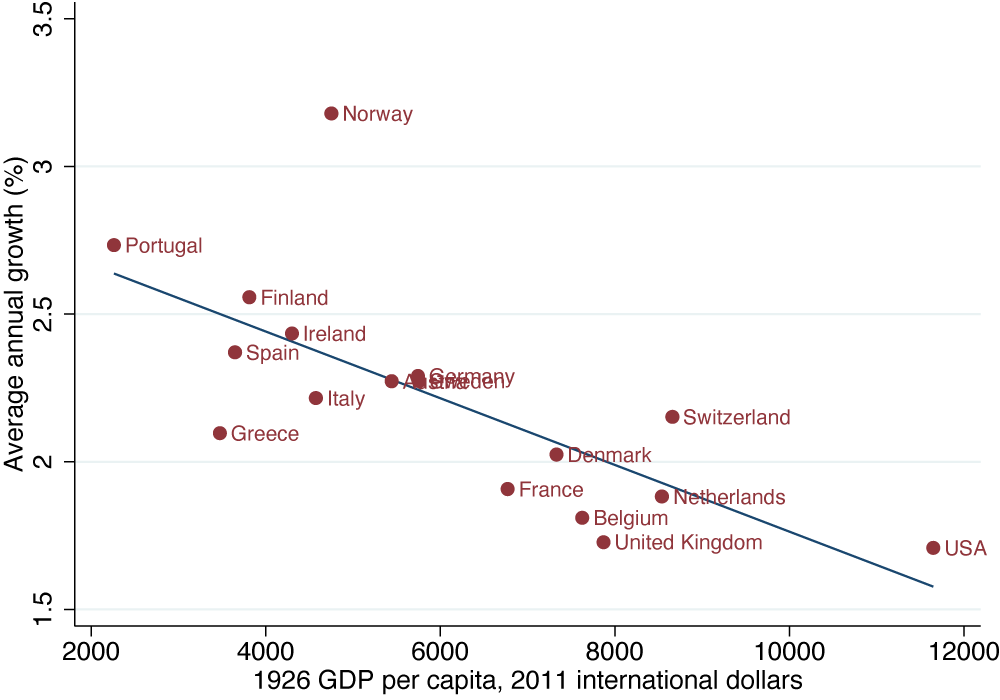

Figure 2 Initial income and subsequent growth, 1926-2018

Source: Ó Gráda and O’Rourke (2021), based on Bolt and van Zanden (2020), data from the Central Statistics Office, and data kindly provided by Rebecca Stuart.

The real costs of the strategy arose in the 1950s, when Europe embarked on its Golden Age and protectionist Ireland was left behind, despite its nascent strategy of attracting foreign direct investment. More surprisingly, Ireland remained a striking under-performer in the 1960s, a reflection perhaps of its strong ties with the UK, then the sick man of Europe. It was only when Ireland joined the European Communities in 1973 that it stopped losing ground vis à vis the continent, and it was only in the late 1980s that it finally, belatedly, and dramatically converged on the European core. In a long run perspective, Irish economic growth has been pretty much what would have been expected, given its initial starting point (Figure 2) – on average, it has been a strikingly normal European country.

That conclusion extends to Ireland’s relative economic status today. GDP per capita statistics show the country holding the number two spot in the EU but, as is well-known, GDP has become a hopelessly inadequate guide to the health of the Irish economy. Nor is GNI reliable, largely as a result of the capital assets owned by multinationals located in Ireland, which carry with them large depreciation charges. That is why Figure 2 was calculated using what Irish national accountants call GNI*, which corrects for these distortions. Strikingly, Irish GNI* growth since 2000 has averaged just 0.7% per annum.

Honohan (2021) has recently and forcefully drawn attention to these problems, pointing out that GNI* in Ireland was 40% lower than GDP in 2019, and that Ireland would only be in eighth place in the EU based on this more appropriate yardstick. When measured in terms of consumption, it would rank even lower. In particular, it would rank below the UK, with total household consumption (including consumption of government-provided services) roughly on a par with consumption in Northern Ireland (FitzGerald and Morgenroth 2020, see also Bergin and McGuinness 2021).

In terms of living standards and growth, Ireland is thus a rather run-of-the-mill European economy. Where it stands out is the extent of its links with the rest of the world, as well as its volatility. Take the latter first. We have already mentioned the 1930s, which were disastrous everywhere. There followed WWII, during which Ireland (unusually for a neutral country) suffered a dramatic fall in living standards; the 1950s and 1980s, two decades during which the case for viewing the country as a failed economic entity was a strong one; and the 18% decline in GDP suffered between 2007 and 2012. Inappropriate macroeconomic policy was a factor during the 1950s, 1980s, and 2000s. Fiscal policy has generally been pro-cyclical (Lane 1998), while interest rates were inappropriately low in the aftermath of Ireland’s entry into European Monetary Union. In some cases, however, Irish mistakes have to be seen in a broader international context. Ireland was hardly the only country to engage in stop-go policies during the 1950s and 1960s, or the only recipient of cheap money in the early years of EMU (Middleton 2002, Obstfeld 2013).

A second potential cause of Irish economic volatility is the extent to which its factor markets are integrated with the world economy. This has given the country many of the features of a regional economy, with labour and capital flowing into and out of the economy over the course of the business cycle (Krugman 1997, Barry and Bergin 2019). Migration has provided a crucial safety valve in times of crisis, but inward and outward factor flows clearly have the potential to amplify both booms and busts.

One of the most striking consequences of Ireland’s delayed convergence has been its transformation from a country of large-scale net emigration to a country of equally large-scale net immigration. The absorption of what was, in relative terms, the biggest influx of immigrants in any European economy in recent decades was not painless; research commissioned by the Irish government in the wake of a 2008 referendum rejecting the Lisbon Treaty found that anti-immigrant sentiment was one factor explaining the vote (Sinnott et al. 2009). Still, there was less open xenophobia than elsewhere in Europe (Denny and Ó Gráda 2014). How Irish civil society reacted highlights the distinction between public opinion (which in Ireland has been unexceptional) and salience, i.e. how much the issue of immigration was a priority for voters. Ireland in 2021 remains virtually the only country in western Europe without a sizeable anti-immigrant party.

The extent of Ireland’s dependence on foreign direct investment is also unusual. The strategy of attracting multinational investment goes back to the 1950s, pre-dating the country’s commitment to trade liberalisation by several years. American companies were particularly welcome at the time, in that they did not seem to threaten Irish sovereignty in the way that excessive investment by British firms might have done (Barry and O’Mahony 2017). Entry into the European Communities in 1973, and the Single Market programme of the late 1980s and early 1990s, made Ireland a platform from which these companies could serve the broader European market. Educational reforms and low corporate tax rates also helped; Ireland got away with the latter because of the long-standing nature of the policy, the country’s peripherality and relative economic backwardness, and its small size. But the extent of tax avoidance globally now means that international corporate tax reforms are both inevitable and desirable. If Ireland were merely a home for brass-plate, profit-shifting enterprises it would have little to fear from this, but multinationals are major employers in the country, and the taxes they pay are a major source of government revenue. The hope will be that the country’s other advantages will suffice to maintain its attractiveness to domestic and foreign investors as it adjusts to Brexit.

References

Barry, F and A Bergin (2019), “Export structure, FDI and the rapidity of Ireland’s recovery from crisis”, Economic and Social Review 50: 707-724.

Barry, F and C O’Mahony (2017), “Regime change in 1950s Ireland: The new export-oriented foreign investment strategy”, Irish Economic and Social History 44: 46-65.

Bergin, A and S McGuinness (2021), “Who is better off? Measuring cross-border differences in living standards, opportunities and quality of life on the island of Ireland”, Irish Studies in International Affairs 32: 143-160.

Bolt, J and J L van Zanden (2020), “Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update”, Maddison-Project Working Paper WP-15.

Clemens, M A and J G Williamson (2004), “Why did the tariff–growth correlation change after 1950?”, Journal of Economic Growth 9: 5-46.

Denny, K and C Ó Gráda (2014), “The Irish and immigration before and after the boom”, VoxEU.org, 3 January.

Honohan, P (2021), “Is Ireland really the most prosperous country in Europe?” Economic Letters 2021: 1-8.

Honohan, P and B Walsh (2002), “Catching up with the leaders: The Irish hare”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1-57.

Krugman, P R (1997), “Good news from Ireland: A geographical perspective”, in: Gray, A W (ed.), International perspectives on the Irish economy, Indecon Economics Consultants.

Lane, P R (1998), “On the cyclicality of Irish fiscal policy”, Economic and Social Review 29: 1-16.

Lee, J (1989), Ireland, 1912-1985: Politics and society, Cambridge University Press.

Middleton, R (2002), “Struggling with the impossible: Sterling, the balance of payments and British economic policy, 1949–72”, in A Arnon and W Young (eds), The open economy macromodel: Past, present and future, Springer.

Obstfeld, M (2013), “Finance at center stage: Some lessons of the euro crisis”, European Economy Economic Papers 493.

Ó Gráda, C and K O'Rourke (1996), “Irish economic growth, 1945–88”, in G Toniolo and N Crafts (eds), Economic growth in Europe since 1945, Cambridge University Press

Ó Gráda, C and K H O'Rourke (2000), “Living standards and growth”, In J O'Hagan (ed.), The economy of Ireland: Policy and performance of a European region, Gill and Macmillan.

Ó Gráda, C and K H O'Rourke (2021), “The Irish economy during the century after partition”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15991.

Roche, W K, P J O’Connell and A Prothero (2016), “Introduction ‘poster child’ or ‘beautiful freak’? Austerity and recovery in Ireland”, in W K Roche, P J O’Connell and A Prothero (eds), Austerity and recovery in Ireland: Europe's poster child and the great recession, Oxford University Press.

Sinnott, R, J A Elkink, K O’Rourke and J McBride (2009), Attitudes and behaviour in the referendum on the treaty of Lisbon, Report prepared for the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs.

The Economist (2015), “Getting boomier”, 21 November. Fitzgerald, J and E L W Morgenroth (2020), “The Northern Ireland economy: Problems and prospects”, mimeo.

Endnotes

1 A similar progression may be observed in the writings of the present authors on the subject (Ó Gráda and O’Rourke 1996, 2000).