The efficiency of public procurement directly influences the availability and quality of government-provided goods and services that are often crucial to social welfare and growth. One organisational lever that can be used to improve this efficiency is centralisation, due to its potential to enable speedy and transparent acquisitions without excessive discretion and to limit public spending through buyer power/coordination and economies of scale. Bandiera et al. (2009) first estimated the direct effects of centralisation on public savings, finding that public bodies purchasing through a central agency in Italy save, on average, 28% of the price.

Other recent studies assessed the direct effects of public procurement centralisation on savings and confirmed significant price reductions, which, however, appear diminished when the supply side is more concentrated (Dubois et al. 2021a, 2021b) or countered by a deterioration in other outcomes, such as delivery times (Clark et al. 2021). These studies do not consider possible indirect effects from public administrations that do not purchase through the central agency.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought centralisation to the centre of the public debate (e.g. AMA 2020). Specifically, it was accompanied by a crisis in the public procurement of health-related supplies whereby, at various points, different levels of government and public agencies within a country bid against each other, and widespread abuses of increased discretion were allowed by emergency regulations (Bandiera et al. 2021a, 2021b).

In a new paper (Lotti and Spagnolo 2022), we use the same policy experiment and data on procurement purchases of Bandiera et al. (2009) to estimate the indirect savings from centralisation in terms of price reductions obtained by public administrations that did not buy from the central agency (Consip) but whose purchases followed its entry in the market. The database is the result of a survey designed and implemented by ISTAT, the Italian statistical agency, on purchases of generic goods by a sample of Italian public bodies in the period 1999-2005. We focus on contracts relating to goods that were purchased both before and after Consip entered the market and for which Consip negotiated at least one deal during the sample period. We observe unique, anonymous public bodies identifiers, together with characteristics such as region and governance type, as well as detailed information on the contract and the goods purchased (e.g. price, quantity, brand, model, delivery, and maintenance conditions).

Our empirical strategy is a difference-in-differences design that exploits the fact that Consip’s entrance into different markets took place at different points in time and the data provide us with information on this timing for each market. Unlike Castellani et al. (2018), we do not find evidence of manipulations in the timing of acquisitions by public bodies to avoid delegating the purchase to the central agency, which permits identification. Further, we leverage public bodies fixed effects to control for time-invariant unobserved individual characteristics that may be relevant in determining the choice to buy outside Consip – for example, a preference for quality or vice versa for corrupt practices. We select goods characteristics to be included in our model using machine learning techniques (post-double-selection lasso procedure) to ensure that the choice of control variables is done in a consistent manner that does not lead to wrong estimates of the standard errors. Our results indicate that, when controlling for the characteristics of goods, indirect effects reduce the price of non-centralised purchases by 17.7%, on average.

We then investigate the origin of the estimated indirect effects, exploring two candidate mechanisms: information externalities (benchmarking information) and increased buyers’ outside options. Information externalities stem from the publicly observable lower price that Consip obtains when auctioning framework agreements for a large fraction of Italian public demand (about 40% at the time). This allows public bodies purchasing outside Consip to learn and benchmark their reserve prices against those obtained by Consip and may also discourage or limit corruption because prices can no longer be easily inflated without raising suspicion about the purchase (the law required public bodies to use the quality and price standards of Consip’s agreements as a reference when autonomously purchasing comparable goods). The improved outside option, on the other hand, would be linked to the availability of an active Consip agreement from which public bodies can purchase. In this case, if public bodies fail to reach favourable offers in their decentralised acquisitions, they have the option to switch to the centralised agreement. This option should pressure suppliers to reduce decentralised prices.

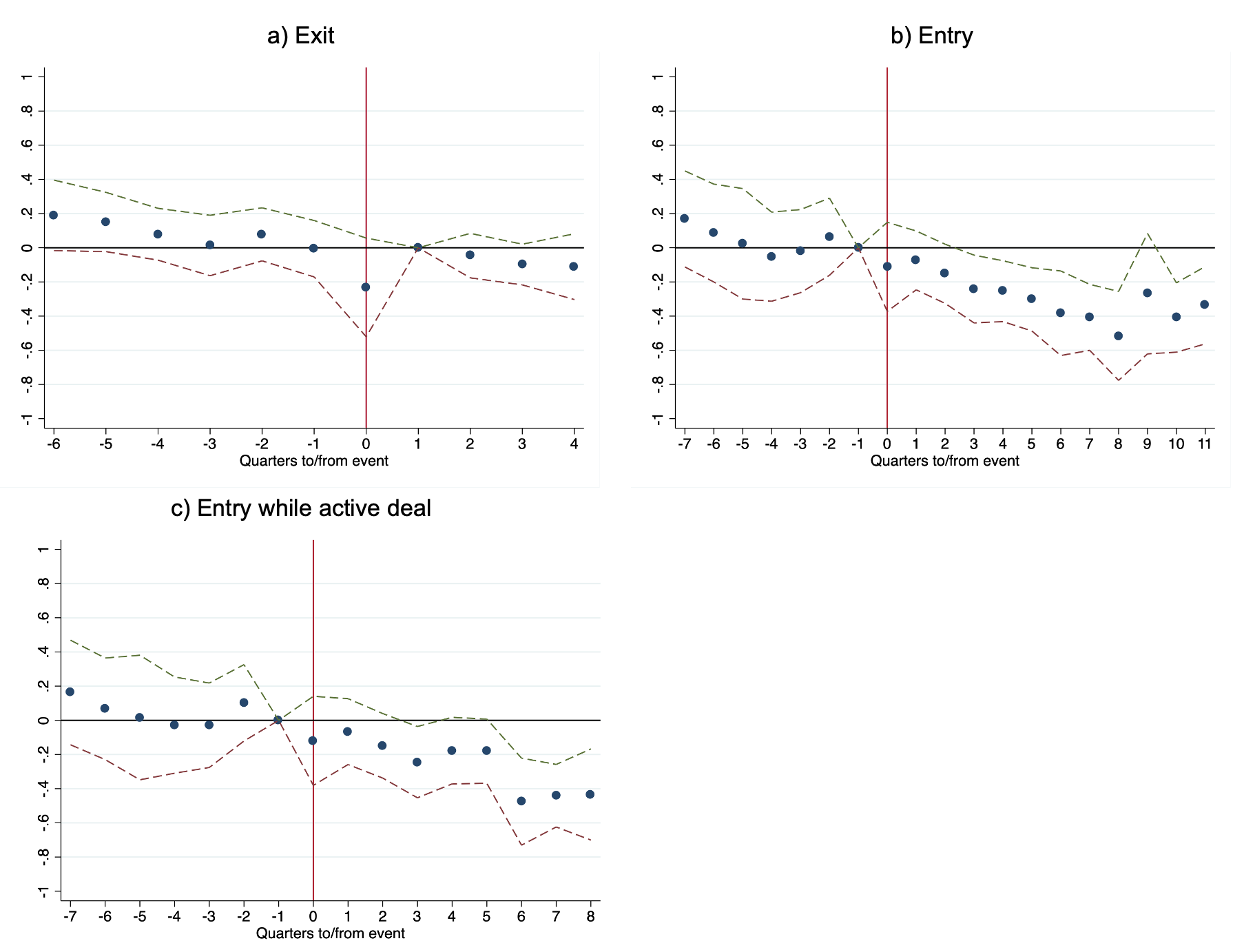

To disentangle the role of these two plausible mechanisms, we exploit the fact that information externalities only depend on Consip’s having previously entered a specific market. Contrary to the improved outside option, they do not require an active central agreement. Our analysis suggests that the indirect effects we estimate are mainly linked to information externalities: the prices of non-centralised purchases do not seem to fluctuate based upon the presence or the expiration of a centralised agreement, which would create or remove the outside option, respectively (see Figure 1).

We then explore the heterogeneity of indirect effects across different types of purchases and buyers. We find that the indirect savings result mainly from complex goods such as laptops, projectors, and fax machines. This is consistent with the effects being driven by informational externalities that – contrary to the improved outside option – are less relevant for simple goods such as paper or copper cable. Furthermore, most of the indirect savings from centralisation are obtained by less competent public buyers. Our preferred interpretation is that the most competent administrations are already able to figure out plausible prices for complex goods in the absence of a central purchasing body, and therefore learn little from the price it obtains. This would be consistent with Bucciol et al. (2020), who find that the introduction of reference prices by a supervisor in the Italian medical devices market reduces prices for less competent public buyers and increases them for more competent ones.

Figure 1 Event study analyses of out-of-Consip prices

Note: The figures display estimated changes in log prices at different lags and leads since the start (end) of the first Consip deal, denoted by a vertical line. All coefficients are expressed relative to the year before entry (after exit); 95% confidence intervals are reported. See Lotti and Spagnolo (2022) for details.

The price of non-centralised purchases is the benchmark that Bandiera et al. (2009) use to estimate the 28% direct savings from buying from the central agency. Our results imply that this benchmark was significantly deflated by the indirect effects, leading to an underestimation of the direct effects. We show that accounting for the indirect effects lifts the estimate of the direct savings up to 46.8%. However, adding brands to Bandiera et al. (2009) controls for quality pushes in the opposite direction, leading to a final revised estimate of direct savings of 29%. This finding highlights that part of the direct savings generated by centralised purchases stem from a tendency of Consip to buy lower value brands, an issue that had not been pointed out until now.

Using our results, we can then calculate the total savings caused by centralisation. If our sample was representative, considering that Consip’s entry led to about 40% of spending moving through the central agency, the average total (direct and indirect) savings caused by this episode of centralisation amounted to 22% of the overall expenditures on goods and services, or to 1.8% of GDP per year (the total expenditure on goods and services was 8% of GDP in the relevant period).

While these findings have clear and important policy implications, we must stress that we are only looking at the monetary benefits of centralisation. We do not measure its many possible costs, for example, standardisation and the resultant mismatch with heterogeneous buyers’ preferences, a lack of control over non-contractible quality through local relationships, or barriers to entry for small and medium-sized firms. Centralisation may also generate other benefits that we are unable to quantify, such as reduced litigation, administrative costs, and corruption. To obtain a complete picture of the effects of public procurement centralisation, future studies should address these other important aspects.

References

American Medical Association (2020), “AMA urges FEMA to act as single national source for acquisition of PPE", 14 April.

Bandiera, O, E Bosio and G Spagnolo (2021a), Procurement in Focus: Rules, Discretion, and Emergencies, CEPR Press.

Bandiera, O, E Bosio and G Spagnolo (2021b), “Discretion, efficiency, and abuse in public procurement: A new eBook”, VoxEU.org, 30 November.

Bandiera, O, A Prat and T Valletti (2009), “Active and Passive Waste in Government Spending: Evidence from a Policy Experiment”, American Economic Review 99(4): 1278-1308.

Bucciol, A, R Camboni and P Valbonesi (2020), “Purchasing medical devices: The role of buyer competence and discretion”, Journal of Health Economics 74: 65-81.

Castellani, L, F Decarolis and G Rovigatti (2018), “Procurement Centralization in the EU: The Case of Italy”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12567.

Clark, R, D Coviello and A De Leverano (2021), “Centralized Procurement and Delivery Times: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Italy”, ZEW - Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper No. 21-063.

Dubois, P, Y Lefouili and S Straub (2021a), “Pooled Procurement of Drugs in Low and Middle Income Countries”, European Economic Review 132: 103655..

Dubois, P, Y Lefouili and S Straub (2021b), “Pooled procurement of drugs in low- and middle-income countries can lower prices and improve access”, VoxEU.org, 30 January.

Grennan, M and A Swanson (2020), “Transparency and Negotiated Prices: The Value of Information in Hospital-Supplier Bargaining”, Journal of Political Economy 128(4): 1234-1268.

Lotti, C and G Spagnolo (2022), “Indirect Savings from Public Procurement Centralization”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17019.