Insurance companies – life insurers, as well as providers of property, casualty, health, and financial coverage – perform important economic functions and are big players in financial markets. Traditionally, however, they were not considered to pose systemic risks. Insurers have longer-term liabilities than banks, a greater diversification of assets, and less extensive interconnections with the rest of the financial system. However, the near-collapse of AIG during the Global Crisis prompted a rethinking of the sector’s systemic riskiness. A number of insurance firms were subsequently among the financial institutions designated as globally systemically important.

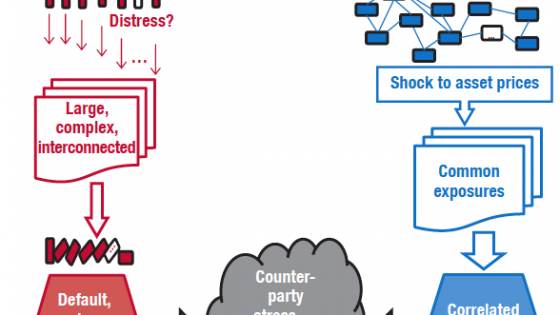

Figure 1 Relative size of financial intermediaries in selected countries (% of GDP)

Note: OFIs = Other financial institutions.

Sources: Haver Analytics; European Central Bank Statistical Data Warehouse; and IMF staff calculations.

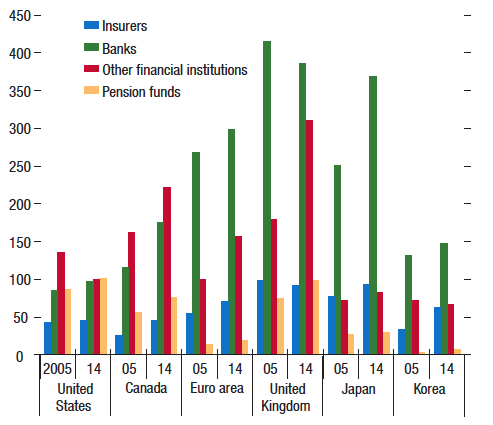

Systemic risk analysis has typically focused on the risks of failure of individual institutions and their potential knock-on effects (the ‘domino’ view of systemic risk; see Acharya 2015). However, the contribution to systemic risk by insurers and other financial firms extends beyond this dimension. In the ‘tsunami’ or macroprudential view, even solvent firms may propagate or amplify shocks to the rest of the financial system and the real economy. Systemic risk may stem from common exposures of a few large firms or many small ones (Acharya 2015, IMF 2013). For example, insurance companies play a critical role in corporate bond markets, and if they are hit by a large common shock, a consequent cessation of funding could hurt other companies badly (Bank of England 2015). In principle, the insurance sector could therefore be a significant contributor to systemic risk even if no single insurance company were systemically important.

Figure 2 Insurance and systemic risk

Source: IMF staff.

We analysed the evolution of the systemic risk contribution of the insurance sector across major advanced economies, and examined drivers behind this evolution in the Global Financial Stability Report (IMF 2016).

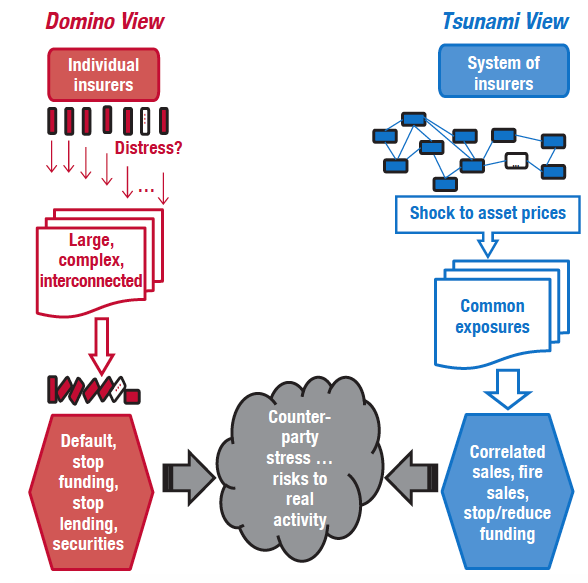

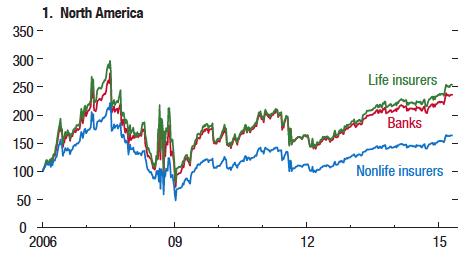

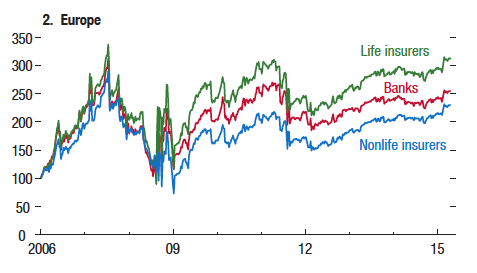

Results from a variety of different methods (which capture aspects relevant to both the tsunami and domino views) point in the same direction: the systemic risk contribution of the life insurance sector has risen since the Global Crisis, as common exposures within the industry and to the rest of the economy have increased. Nevertheless, the sector’s systemic importance remains below that of the banking sector. By contrast, the systemic risk contribution of the non-life insurance sector has generally not increased.

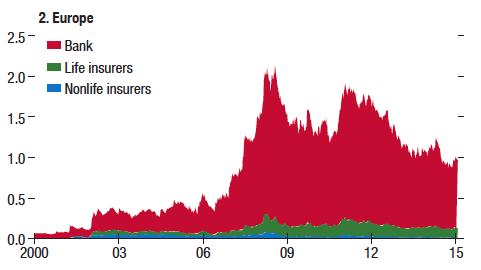

Figure 3 Conditional capital shortfall (US$ trillions)

Note: Figure shows the expected capital shortfall (compared to required capital) for each sector conditional on a prolonged market decline (Brownlees and Engle, forthcoming). Calculations are based on data on a weekly frequency for the period 2 June 2000 through 30 October 2015, calculated using data from the V-Lab at New York University.

Sources: New York University, Stern School of Business, V-Lab; and IMF staff calculations.

Figure 4 CoVaR indices (normalised, 2006 = 100)

Note: An institution’s CoVaR relative to the system is the value at risk of the whole financial sector conditional on that institution’s particular state. The difference between the CoVaR conditional on an institution being in distress and the CoVaR conditional on the ‘normal’ state of the institution ΔCoVaR, captures the contribution of an institution, in a non-causal sense, to overall systemic risk (Adrian and Brunnermeier 2016). Figure shows CoVaR indices constructed by aggregating the average ΔCoVaR of individual firms for all firms in a given sector and region, normalised by their value in the first period. The estimation corrects for the effects of market risk (MSCI World Index) and volatility risk (an average of volatility indices in North America, Europe, and advanced Asia).

Sources: Bloomberg, L.P.; and IMF staff calculations.

This increase in systemic risk contribution has come along with an increase in equity price co-movements and higher common risk exposures.

Figure 5 Variation of insurers’ equity return due to first principal component (%)

Note: Figure shows explanatory power (R2) of first principal component of US and European insurers’ equity returns, using daily data (2004 through 15). Period I is before the crisis, and Period II is after the crisis. Crisis is July 2007 through December 2008 for the US, and July 2009 through December 2011 for Europe.

Sources: Bloomberg, L.P.; J.P. Morgan; and IMF staff calculations.

The higher common exposures seem to be driven partly by duration mismatches and broader market forces, not by overt portfolio shifts. An analysis of micro data of insurers’ portfolios across various countries does not suggest that portfolio compositions have become markedly more similar. However, because of duration mismatches, life insurers have become increasingly sensitive to interest rates as interest rates have fallen. Moreover, cross-asset correlations have risen in recent years (likely at least partly due to structural factors), increasing the riskiness of pre-existing exposures.

Overall, insurers do not seem to have actively shifted their portfolios toward riskier categories of assets. However, because insurers have not counteracted market forces in their asset choices, they have become more exposed to aggregate risk. The behaviour of smaller and weaker companies, however, has been different. Firm-level case studies suggest that, as interest rates decline, smaller life insurers, those with weaker capital positions, and those with higher shares of guaranteed liabilities, tend to take on relatively more risk.

Figure 6 Sensitivity of life insurers' risky assets to firm-level factors (% of total assets)

Note: Figures show the economic impact of firm factors on the share of higher-risk assets, with differentiation between high and low interest rate environments, where significant.

The rise in exposures to aggregate risk means that insurers are more likely to be adversely hit jointly with other segments of the financial sector. In the event of an adverse shock, insurers are unlikely to fulfil their role as financial intermediaries precisely when other parts of the system are also failing to do so.

Taken together, the findings suggest that supervisors and regulators should take a more macroprudential approach to the sector. Doing so is necessary if supervision is to go beyond the solvency and contagion risks of individual firms and take on the systemic risk arising from common exposures. A step that would complement a push for stronger macroprudential policies would be the international adoption of capital and transparency standards for the sector. In addition, attention to smaller and weaker firms is also warranted since they are most likely to take on excessive risks.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Acharya, V V (2015) “Are insurance firms systemically important?” presentation at Stockholm Institute for Financial Research, 15 August.

Adrian, T and M K Brunnermeier (2016) “CoVaR”, American Economic Review, 106(7): 1705-1741.

Bank of England (2015) “Insurance and financial stability”, Quarterly Bulletin, 55(3): 242-58.

Brownless, C T and R F Engle (forthcoming) “SRISK: A conditional capital shortfall measure of systemic risk”, The Review of Financial Studies.

IMF (2013) “Key aspects of macroprudential policy”.

IMF (2016) “The insurance sector: Trends and systemic risk implications”, in Global Financial Stability Report (April).